A mother got into her unreliable Chevy Suburban one night with her four children in South Texas after her husband beat her with the metal end of a belt. Their Suburban started that night and they drove north until they ran out of gas.

They ran out of gas in Dallas and the mother called 911. The operator directed her to the Genesis Women’s Shelter.

According to the shelter’s Executive Director Susan Wells Jenevein, the family of five was taken in to start their lives over after enduring abuse and living in terrible conditions.

Domestic violence has become a central issue for Dallas and for Mayor Mike Rawlings after victim Karen Cox Smith was killed in the parking lot of UT Southwestern Medical Center on Jan. 8, 2013, after 19 years of abuse. Rawlings’ mother was a patient in the hospital during the killing.

On March 23, 2013, nearly 5,000 people attended a downtown Dallas rally hosted by Rawlings that asked the men of Dallas to take a stand against domestic violence. Rawlings is the first metropolitan mayor that has taken a public stance against domestic violence.

In the nine months following the rally, Rawlings, Dallas Police Department (DPD), local shelters, the District Attorney and local courts have worked to increase public awareness and change the way domestic violence cases are handled.

“You can call a guy who hits a woman a lot of things, but a man isn’t one of them” Rawlings said in a Dallas Men Against Violence commercial. “I am a man saying enough is enough.”

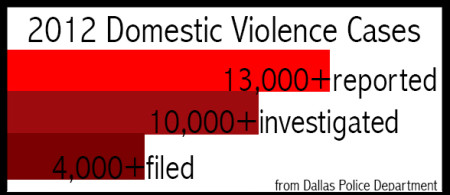

Of the 13,000 domestic violence offenses reported in Dallas since October 2012, over 8,000 are intimate partner cases, according to DPD’s Domestic Violence Unit Lt. Miguel Sarmiento. There has been a 2 to 3 percent decrease of incidents and a 13 percent increase in prosecuted cases.

The unit began making changes about a year-and-a-half ago. In 2012, the Lethality Assessment Program was implemented for dealing with domestic violence incidents. LAP is an 11-question assessment designed to help a detective perceive warning signs for individuals who need shelter or help.

“We spend more time with the victim and we offer them services rather than just walking away and wondering if they ever got help,” Sarmiento said.

The department is updating to a computer system that can track the different types of domestic violence. In order to investigate cases thoroughly, the 30-detective unit plans to add five detectives. In January 2014, a new program, based on the New York Police Department, will be implemented to decrease the number of people lost in the system by focusing on home visits for high-risk individuals.

In conjunction with several groups, the department works on task forces, conferences and events. The mayor’s task force, led by Dallas City Council member Jennifer Staubauch Gates, includes the Chief of Police, District Attorney, Genesis Women’s Center, The Family Place and advocates.

According to Sarmiento, the department relies on shelters for 24-hour crisis lines and to take in victims. The Genesis Women’s Shelter has two shelters and an outreach program that provides counseling, therapy and classes. The emergency shelter offers a victim and her children a place to live for up to six weeks. Annie’s House is a 19-apartment transitional housing unit with an on-site school that clients can apply to live in if they are employed or employable.

Domestic violence is a cross-cultural and cross-socioeconomic issue.

“We have clients we have to turn off the GPS tracker in their new BMW’s and we have clients who can’t afford a car,” Jenevein said. “It doesn’t matter what she looks like. It matters what he does.”

About 75 percent of women killed by their abusers are killed after leaving.

“It’s so dangerous to leave, with your little children typically with no resources,” Jenevein said. “I think these women are incredible. It’s changed me when I get to witness these acts of courage.”

Jenevein began working at Genesis after a colleague in the Junior League of Dallas was killed by her husband with a pair of scissors in front of her children in 2000. She believes that people around domestic violence victims need to be able to speak up when they see the signs.

A change that Jenevein, Sarmiento and rally project manager Shawn Williams have noticed is that people are more likely talk about domestic violence.

“When people see some of the signs or hear something they think that maybe be this is part of this [domestic violence]. That is different than before the rally. People are willing to talk about it, before people didn’t talk about it much,” Williams said.

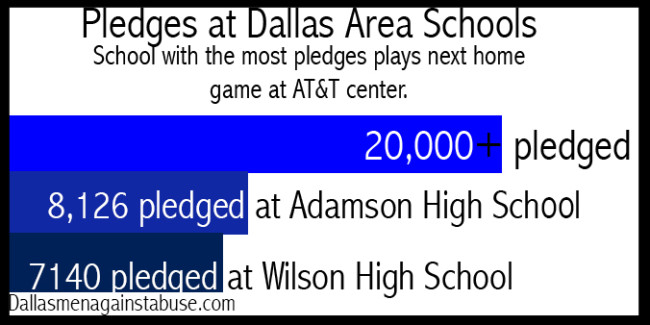

Recently, Rawlings’ initiative went to Dallas Independent School District, Richardson Independent School District, Jesuit College Preparatory School and Bishop Dunne Catholic School. According the Dallas Men Against Abuse website, more than 20,000 people took the pledge against domestic violence from Nov. 3 to 10, 2013, at high school varsity football home games.

Woodrow Wilson High School’s Varsity Coach Daniel Estes thought it was a “natural progression to come to football players.”

“It’s our responsibility to teach character and morality and we can do that on the football field,” Estes said. “Emphasize the right way to play football but also the right way to treat one another.”

Wilson’s football program has about 105 14-to-18-year-old players. Rawlings’ initiative opened up communication lines for Estes and his players.

“There were several players on my team that had witness [ed] domestic violence whether it be a boyfriend or stepdad or dad,” Estes said. “In one case, the violence trickled down to them.”

Rawlings and other civic leaders are members of Genesis’ He Respects Others program that focuses on providing positive male role models for families.

“If it changes one or two kid’s life, it’s well worth it,” Estes said. “If we continue to put it out in the forefront, that domestic violence is not acceptable, then hopefully there will be a change. This is a small drop in the river. If that drop continues it will change.”

The family from South Texas lived in Annie’s House until Habitat for Humanity built them a home. The mother received her nurses assistant degree and a year later her oldest son entered college as an engineering major.

“I think about them a lot,” Jenevein said. “The eldest daughter is in college now. It’s fun to see their lives thrive.”