Sleep remains a struggle. She lies on the floor of her closet. Pepper spray, a knife, a cell phone and her dog are at her side. Panic attacks and nightmares interrupt the sleep she does manage to get.

The event responsible for this took place more than four years ago on the SMU campus. A stranger drugged and raped her. Most rape victims never report the crime. Robin Reed refused to be silent. She spoke up – to campus and Dallas police, to the SMU community, to anyone willing to listen. Breaking the silence taught her an invaluable lesson.

“If you can find the words to talk about something that is so unspeakable,” said Reed, “you can get your power back.”

It was Nov. 22, 2003, a Saturday. Reed, then 19, was a senior at SMU. She moved to Dallas at the age of two with her family. At SMU, she majored in anthropology and foreign languages (French and Spanish), and minored in Latin American studies and women’s studies.

At about 7 p.m., Reed parked her car in the Airline parking garage, and then walked to Fondren Library. Normally, she didn’t spend Saturday nights studying at the library, but she had been working on her senior thesis for departmental distinction in anthropology at home and realized she needed more sources. Reed entered the library alone, found a place to study and set her books, water bottle and backpack down. Later, she left to use the bathroom, leaving the water bottle, books and backpack behind. Reed returned and resumed her study, taking an occasional sip of water. Around 9 p.m., she started to feel sick and decided to leave. She gathered her belongings and began walking to her car.

The next thing Reed remembers is waking up on the front bench seat of her car. She was unable to recall how she got there though almost an hour had passed since she’d left the library. The car door was open, her pants were down, her shoes were off and she was feeling significant pain in her vagina. At 10:35 p.m., she called the SMU Police Department. Officers arrived, began questioning her and called an ambulance.

At first, Reed struggled to explain what had happened. She was disoriented, felt strange and couldn’t remember anything prior to leaving the library. But as her senses cleared, Reed told police and an emergency medical technician she thought someone had raped her. The police listened and said little. Reed was put in the ambulance. Police did not tell her she was being taken to a hospital that did not perform rape examinations.

The medical staff there eventually decided to send her to Parkland Memorial Hospital, the only local medical facility that performs rape examinations. She arrived by ambulance at midnight.

But there was a problem. Before a doctor could perform a rape exam, Parkland officials required a police report. They called the Dallas Police Department. An officer arrived and interviewed Reed. It was not a comforting experience. According to Reed, the officer was “really kind of blaming me for what happened.”

“Her parting words to me were, ‘I hope this is a lesson to you,'” said Reed.

The report turned out to be useless. Dallas police had no jurisdiction over the SMU campus. That was the responsibility of SMU police. This presented another problem. SMU police had classified the incident as a medical call, not a sexual assault. Before Parkland could proceed, campus police had to open a new investigation. Parkland contacted SMU. It was now close to 3 a.m.

Robert Reed, Robin’s father, had been calling for hours on her cell phone. He was worried – his daughter had been expected home hours ago. She couldn’t bear to answer the phone and tell him what had happened. While waiting for SMU police to arrive, Robin called and told him she was at Parkland. She gave no details. She didn’t have to. The word Parkland was enough to bring her father to the emergency room. She did not tell him SMU police refused to believe she had been raped.

At 4:30 a.m., an SMU criminal investigator arrived at Parkland and interviewed Reed, her third such session since the assault.

After the interview was completed, the hospital personnel performed the rape examination. Almost seven hours had passed since Reed had been attacked.

Once the exam was completed, SMU police asked Robin to return to campus and show them what happened. It was 7 a.m.

“It was so hard going back and doing the walk-through and feeling just so incredibly vulnerable,” she said.

Over the course of 10 hours, Reed had been drugged, sexually assaulted, grilled by three police officers, taken to two hospitals, undergone a rape exam and endured a walk-through of the crime scene. Finally, at 8 a.m. on Sunday, Reed returned home. Though exhausted, she couldn’t sleep, couldn’t eat, couldn’t function.

She was still feeling the effects of the drug she believed had been put in her water at the library.

On Monday, Reed went to the SMU Health Center and met with Dr. Nancy Merrill. Reed said Dr. Merrill found several things the Parkland staff overlooked including scrapes and cuts not photographed in the rape exam. However, only rape exams from Parkland are admissible in court. Reed said SMU police did not use Dr. Merrill’s findings. Those findings, according to Reed, were consistent with sexual assault.

The next day, The Daily Campus published an article based on an interview with Robin. The headline read: “Student raped in Airline garage.” The story started a campus uproar.

Robin said SMU officials called the health center and requested her medical file, but Dr. Merrill said federal regulations prevented her from releasing it. Instead, Reed gave Dr. Merrill permission to give police a statement summarizing her findings.

On Wednesday, SMU issued a crime alert about what happened. The headline read, “Student reports assault in Airline garage.”

The next day was Thanksgiving. Final exams would begin in two weeks. Reed took incompletes in her classes. For the next several months, said Reed, her behavior could best be described as “unglued.”

In a private meeting, police told Reed she had not been sexually assaulted. They based this on the absence of semen in the Parkland rape exam, Reed said. In the daily crime logs, police only said a student told them she was “feeling ill.”

Police never found the man who raped Reed. She was left to deal with the effects of a rape that was very real but which SMU police told her had not happened.

In a recent interview, SMU Police Chief Richard Shafer said his department closed the case after a lengthy investigation. When asked why police told Reed privately she had not been raped, the police chief declined to comment.

In the spring of 2004, Reed returned to SMU. It was her semester from hell. Panic attacks and nightmares led to sleepless nights. Her sense of safety had been destroyed.

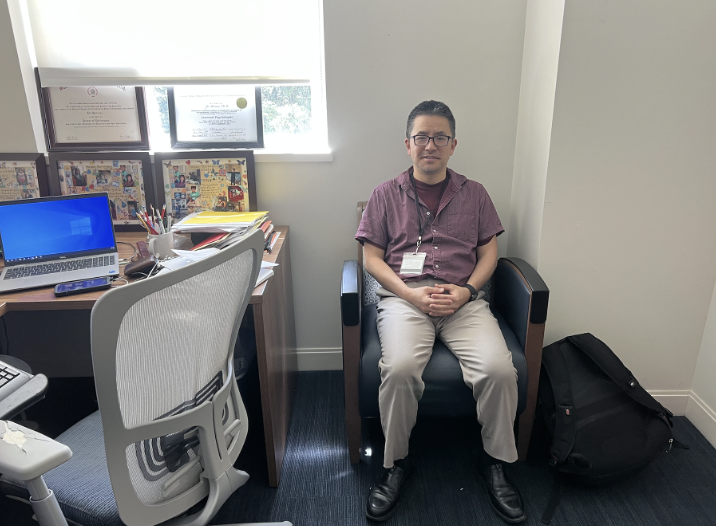

Reed attended counseling sessions with Dr. Cathey Soutter, the SMU director of psychological services for women. For a time, she saw Dr. Soutter almost daily. She spent time at the SMU Women’s Center, the only place on campus she felt safe. She bought a big, black dog and named her Abri, the French word for “shelter” or “hiding place.” She had tea regularly with Dr. Victoria Lockwood, an anthropology professor who had taught her several classes. Their talks comforted Reed and impressed Dr. Lockwood.

“She didn’t feel like a victimized person,” Dr. Lockwood said. “She had a lot of spiritual support and that’s what she focused on, and that was very positive for her. She became more of an activist afterwards.”

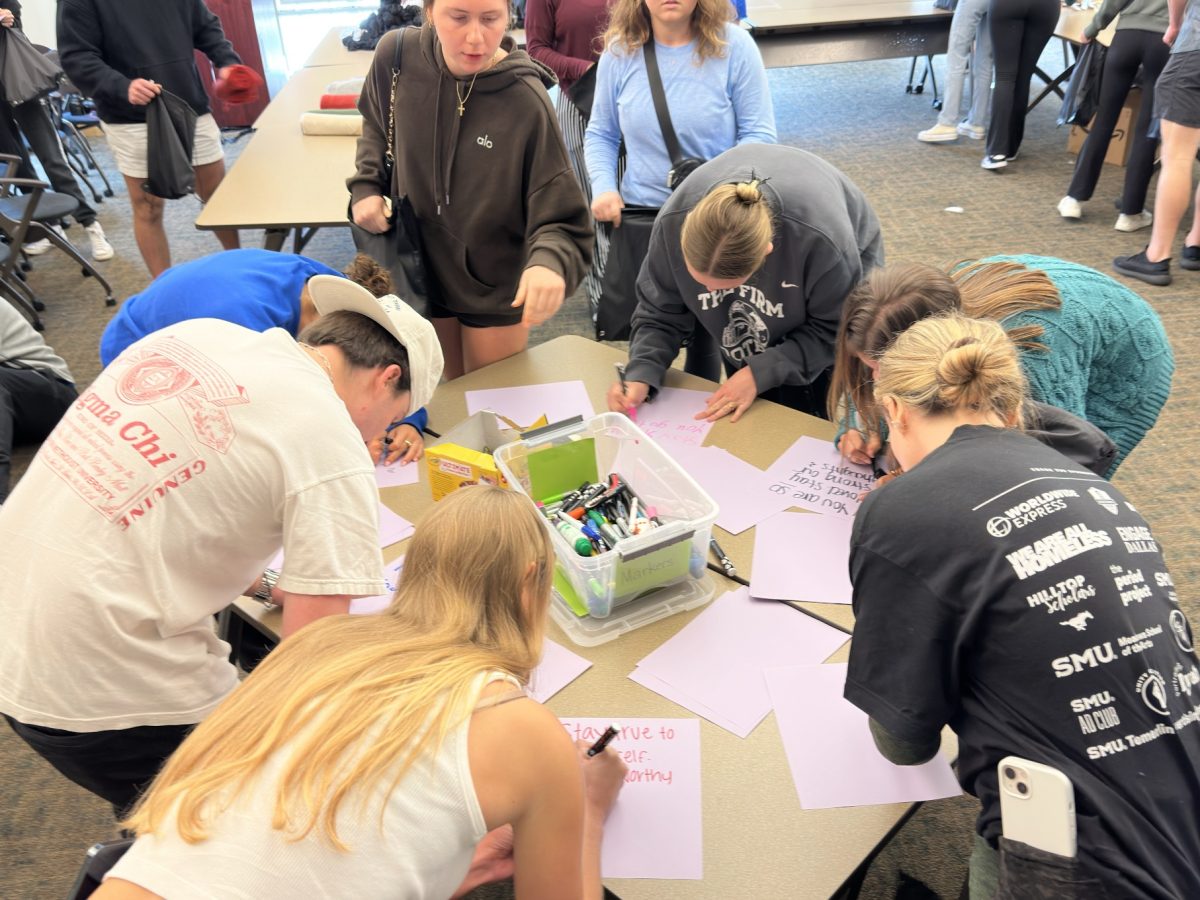

Counseling played a major role in her recovery. She joined the Texas Association Against Sexual Assaults, an advocacy group that promotes education as a way to fight sexual violence. She spoke openly about being sexually assaulted on campus and at events hosted by the Texas group. She is one of the faces of that group’s media campaign “Speak Up, Speak Out.”

During her senior year, Reed wrote an article for The Daily Campus about being raped. “Speaking out and fighting back,” read the headline. In it, Reed talked about the pain of hearing other students discuss what happened to her, “insinuating that I was not really assaulted or that I enjoyed it.” She said the United States has one of the highest reported rates of sexual assault in the world and asked, “What are you doing to fix it?”

In 2005, Reed graduated from SMU, earning degrees in anthropology and foreign languages. Now living in California, she recently got married. Reed hopes to enroll soon in a doctoral program in medical anthropology with a focus on women’s health. She has found healing and wants others to find it too.

“I didn’t want the rapist to silence me, and I didn’t just want to carry it around,” she said. “I felt like I had to talk about it. The only way of getting it out of my system was to talk about it and to write about it and to make it known that that’s what happened.”