Dallas is a city built for its people. Architect James Pratt laid the foundation of this pedestrian-friendly city six decades ago when he began to design and restore Dallas to a modern yet human place.

Pratt drew inspiration from his books, travels and surroundings. He used his studies and experiences to design structures that were collaborative and inventive.

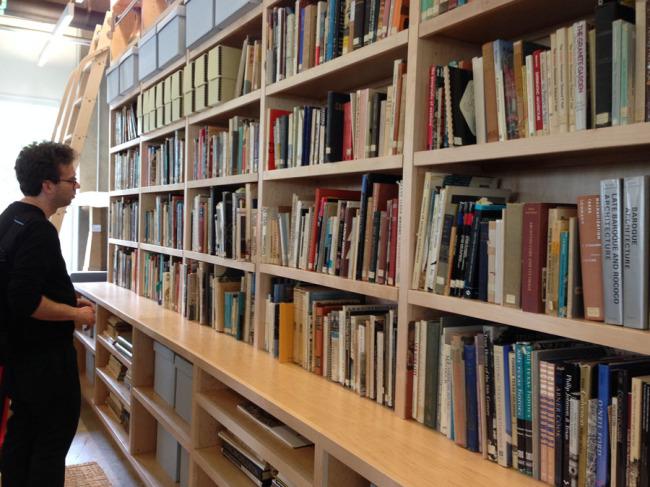

Pratt chose to donate The James Pratt Collection on Urbanism, Architecture, Art and Humanity to the Hunt Institute for Engineering and Humanity because of his connection to Dallas and SMU. His personal collection of first-edition books, architecture-related magazines, monographs and other research materials was dedicated to SMU’s campus Monday. It will open to students and the public Oct. 1.

“With this collection we can […] catch a glimpse into James, his career and what was in the background when James was creating,” keynote speaker Peter Brown, AIA, said. “It speaks into the humanity of architecture.”

Brown stated that Pratt was more than just a visionary architect. He was also a humanitarian, addressing the designs of his buildings on a civic, business, religious, retail and educational scale in order to tie where people live to who they are as individuals. The collection provides an insight into the inspirations in Pratt’s practice and his influences on the city of Dallas.

The Hunt Institute works to shift poverty through innovation, action and empowerment instead of through charity. The Institute combines minds from various fields of interest to improve living conditions and solve humanitarian issues. It is this common goal between Pratt’s work and the Hunt Institute that connects the lifework of Pratt to the Lyle School of Engineering.

Pratt said that his library will improve the already strong academic departments at SMU and might become a catalyst for creating a master of architecture degree within the university.

Hunter Hunt hopes the collection will encourage SMU students to create something new and different. It will also act as a resource for engineering students wishing to work in the humanitarian field.

“This is the essence of what we’ve been trying to push,” Hunt said.

According to Director of the Hunt Institute for Engineering and Humanity Eva Casky, 38 percent of Americans live in poverty. One million people in Dallas alone contribute to this percentage. Casky believes that the new collection will improve these numbers because, “innovation and engineering have the power to influence communities,” she said.

Pratt lived and worked by the same principles, working to make Dallas a better community.

According to The Pratt Collection Notebook, Pratt’s contributions to Dallas extended beyond the tangible. He was able to use design to lessen racial disparities, reverse urban sprawl and promote urbanization.

“He never saw Dallas as it was, preferring to see visions of future developments instead, 10, 20, 50 years away,” The Pratt Collection Notebook states.

Pratt’s major contributions include work connecting Fair Park to downtown and the Dallas Convention Center, improving the Trinity River corridor, creating the Quadrangle shopping center, Brookhaven College and the St. Stephen United Methodist Church. He also restored the 1893 Dallas County Courthouse and the Federal Reserve Bank façade and completed Exposition Plaza.

Brown stated that every project Pratt worked on had an understanding of scale and what it means to design for cities and people. His work and collection now acts as a bridge for the next generation of architects and engineers.

As Brown asked the audience: “The city is on the watch of your generation. What will you do with it?”