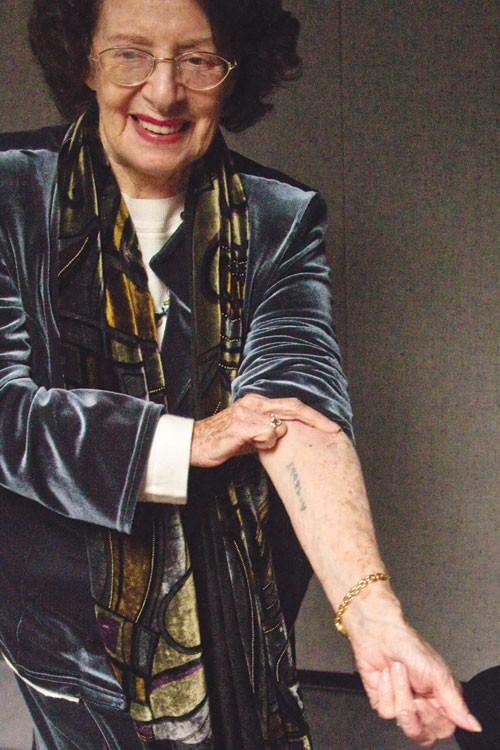

Holocaust survivor Agi Geva shows a serial number tattooed on her left forearm during a lecture Monday evening which was given to Auschwitz concentration camp detainees selected for forced labor. (SPENCER EGGERS/The Daily Campus)

Holocaust survivor Agi Geva described her experience as a Jew during World War II and what it means to be a survivor Monday night as part of the Division of Communication Studies symposium.

On March 19, 1944, the Germans invaded Hungary. Geza, 14 at the time, said, “I had a happy childhood. I couldn’t have dreamed of what was going to happen in the next few months.”

After the invasion, Geza, her mother and younger sister were forced to vacate their home and were taken to a ghetto. Soon after, the Nazi soldiers led them to a train and explained they were being “deported.”

Approximately 30 to 40 people were shoved into each train car for three days. Little did they know they were being taken to the largest concentration and extermination camp: Auschwitz.

After arriving, soldiers began the selection process. Those deemed able to work were sent to the right and admitted to the camp. The elderly, pregnant or sickly were forced to the left and instantly killed.

Geza’s mother realized that in order to stay together they could not give any indication they were family.

At gunpoint, they were forced to undress and led to showers. The humiliation continued as they were forced to shave the hair off their entire bodies for disinfectant purposes.

“Everything was grey in Auschwitz, from the clothes to the blankets to the food. Even the sky was grey,” Geza said.

After 10 days, they were transferred to Plaszow. There they were put to strenuous work but Geza decided nothing could be worse than Auschwitz.

“One day we heard cannon shots and thought the Russians were coming to save us but the Germans had other plans,” Geza said.

They were once again forced onto a train.

After days of traveling, the doors opened and they were back in Auschwitz.

Again, they encountered a harsh selection process. With the weight they had lost and their physical exhaustion, it was difficult to demonstrate their capacity to work to the Germans.

Both her mother and sister made it past the soldier and were sent to the right. When the soldier came to Geza, he pointed to the left.

She pleaded with him and convinced him she was healthy and ready to work. After much deliberation, she succeeded in joining her mother and sister.

A short time later, she, her family and others sent to the right were transported to a small labor camp in Rochlitz, Austria. Here they were trained to do factory work.

After several months at a factory in Cawl, Germany, the women were forced on a march of 400-kilometers. On April 28, 1945, American soldiers liberated the women on the march.

At 19, Geza and her sister moved to Israel. Five years later, their mother joined them.

Today, Geza lives in Washington, D.C. where she is currently a volunteer at the U.S. Holocaust Museum.

Pointing to a picture of her family, Geza said, “No one in this picture would be here if my mother hadn’t saved my sister and me. Not a day goes by where I don’t think about that.”

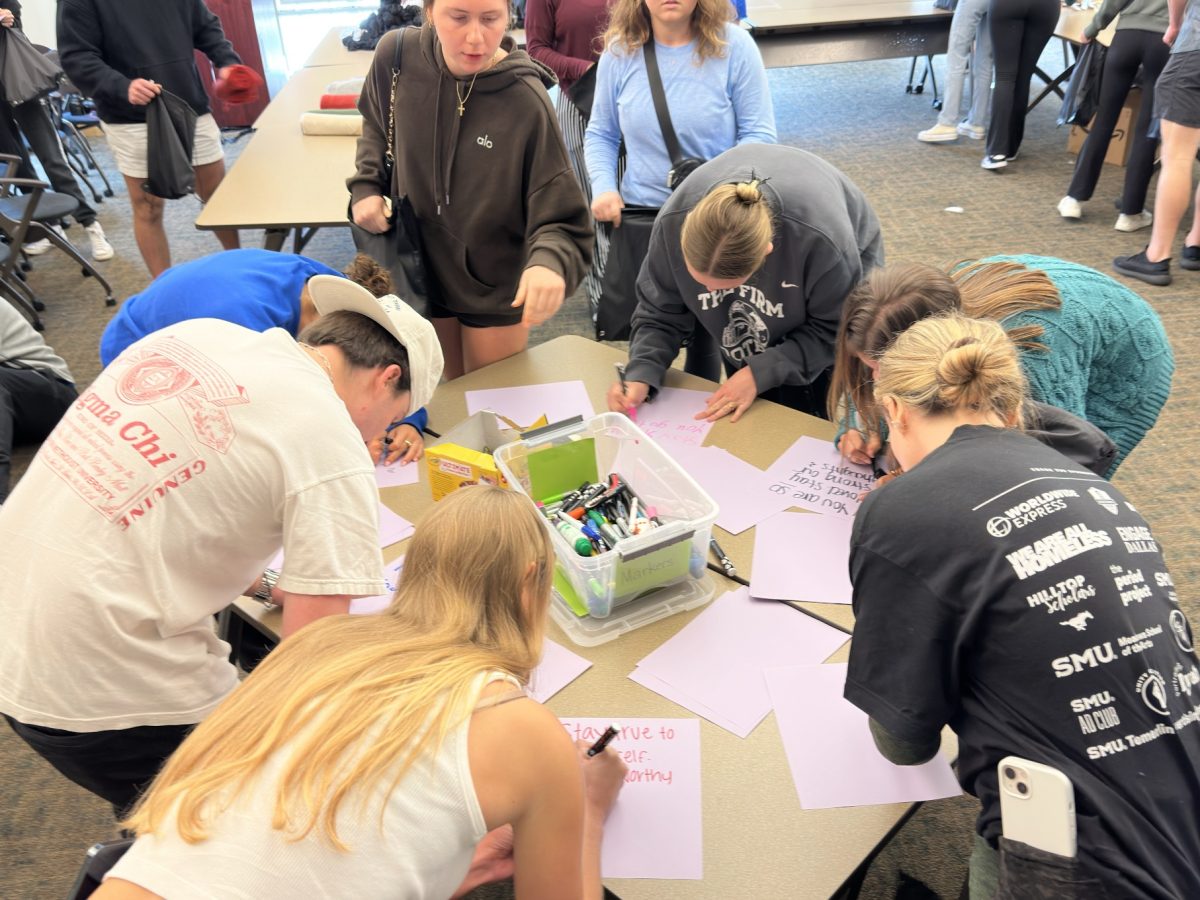

March 7 to 9 marks the Division of Communication Studies’ fourth annual “Communicating Excellence Symposium” at SMU’s Meadows School of the Arts. The purpose being to promote “better communication for better leaders on human rights.”