Marika Wynne expected to go through four years of college when she entered SMU in the fall of 2009. But after a conversation with her academic advisor last spring, something changed: she’s graduating in three years instead.

“I wish I could do a victory lap, but it’s just not cost effective,” said Wynne, a senior dance major who has been taking an 18-hour load each semester so she can graduate in May.

Tuition is the dominant reason that Wynne cannot afford a fourth year at SMU. However, she said the general student fees also played a large role in her decision to graduate early.

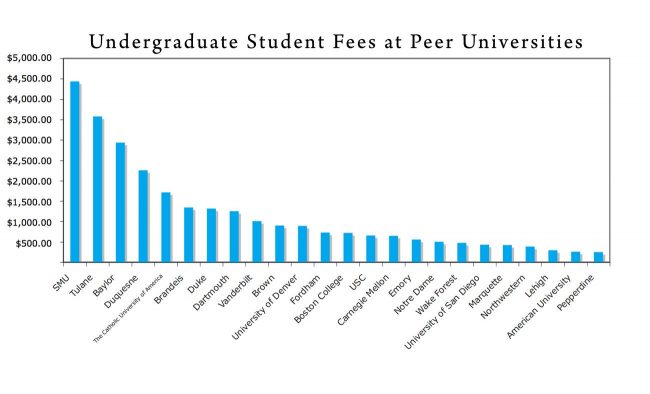

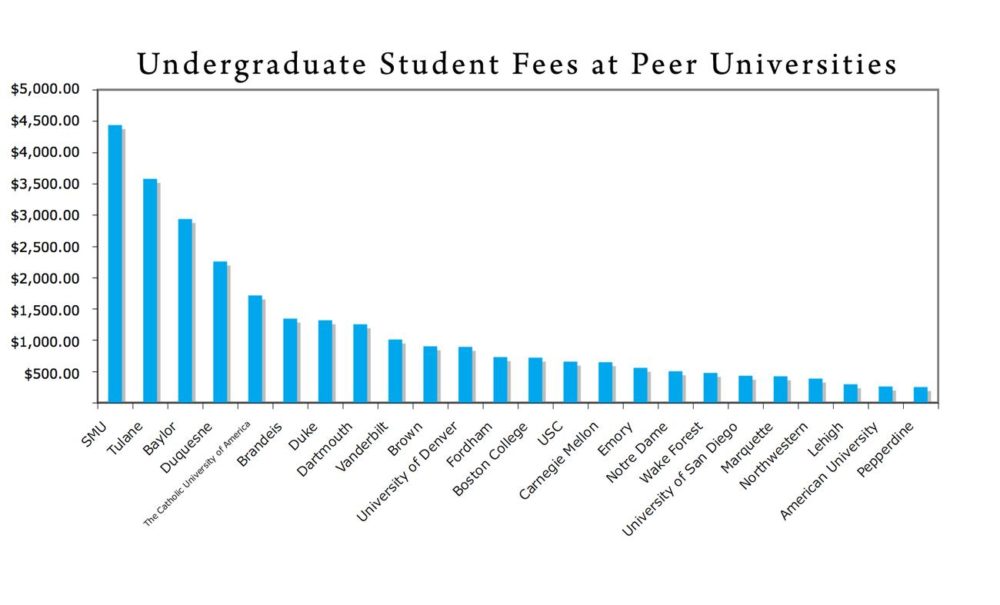

SMU charged its full-time, undergraduate students $4,440 in student fees this year, yet the university’s administration won’t provide a specific breakdown for where the money goes. This amount is, for the most part, thousands of dollars higher than all 24 of SMU’s peer universities, leaving Wynne and other students wondering what they are paying for.

“If they’re called student fees, they must be for us in some capacity,” Wynne said. “I think that if you are paying, you have the right to know what you’re paying for.”

A visit to the SMU website does not completely answer this question; nor did multiple inquiries to school officials.

Administrators will give a vague breakdown, but nothing in writing gives students a numerical dissection of how their fees are allocated.

“While we don’t release specific lists, student fees cover a broad array of activities and campus programming that are key to the SMU student experience,” SMU Vice President for Business and Finance Chris Regis said in an e-mail. “General fees fund various programs and activities on campus such as the Hughes-Trigg Student Center, Dedman Center for Lifetime Sports, student association programs and intercollegiate athletics.”

Most of SMU’s peer universities numerically break down student fees on their websites. For example, student fees at Notre Dame are $507 for the 2011-2012 school year. Fees include a $250 technology fee, a $150 health center access fee, a $95 student activity fee and a $12 Observer fee (the student newspaper). Notre Dame has the third lowest fees among SMU’s 12 peer benchmark universities.

“Our fees are broken down and right now we think that’s the right thing to do,” said Joseph Russo, director of student financial strategies at Notre Dame. “Transparency, especially today, is expected from consumers.”

When asked why SMU student fees are the highest out of its peers, Regis said in another e-mail that “some schools place more emphasis on tuition versus fees,” and that SMU falls in the middle of its peers when looking at the combined cost of tuition and fees.

Dartmouth College is one of the peer benchmark universities that matches this description. This year, tuition at Dartmouth is $41,736 and student fees are $1,260, compared to SMU’s $34,990 tuition and $4,440 student fees. Like Notre Dame, however, Dartmouth provides a breakdown on its website for where student fees are allocated.

Ron Hiser, Dartmouth’s director of student financial services, acknowledged that while the combined amount of tuition and fees at Dartmouth totals higher than SMU, transparency is crucial since college is such a pricey investment.

Hiser said that he wasn’t sure that SMU’s failure to provide a breakdown of fees is right or wrong, but if the same thing went on at Dartmouth, people would want answers.

“At least we’re trying to make it clear what the charges are,” he said, “not that people still don’t complain that we charge too much.”

According to Hiser, Dartmouth used to charge tuition and fees together, but administrators decided to separate the two categories so they could display the specific charges assigned for student fees. For 2011 to 2012, Dartmouth’s student fees included a $225 health access fee, $234 for student activities and an $801 general student services fee, which covers technology costs, library services and facilities and recreation activities and facilities, among others.

“It makes it easier to explain what the charges are,” Hiser said. “By being transparent then you don’t have to spend a lot of time helping them understand it.”

According to Regis, part of the money collected from fees funds student tickets to SMU sporting events – a feature that Wynne believes many students would forego if they had the option.

“I know a lot of the student body doesn’t take advantage of it and if students had the option to not pay for it, I’m sure they’d take it,” she said.

Dan Fulks, an accounting professor at Transylvania University in Lexington, Ky., agrees with Wynne’s opt-in, opt-out idea for determining student fees.

“The ideal business model would be that students pay for what they use,” he said. “If you’re not making use for recreation and not getting tickets for athletic events, you probably shouldn’t pay for that fee.”

An SMU enrollment executive says a “pay for what you use” approach isn’t necessarily realistic.

“The fees provide a lot of things that not every student takes advantage of,” said Pat Woods, the executive director of enrollment services in the Bursar’s office. “But you have to take care of those things whether you’re a full-time student or not.”

Taking care of university finances is one thing, but it is another to raise tuition and fees by about 6 percent every year.

According to the Office of Institutional Research on the SMU website, tuition for the 2012-2013 school year will rise by 5.9 percent to $37,050. Student fees will also rise by 5.9 percent to $4,700.

“I don’t see the fruit of the labor of paying more and more each year,” Wynne said. “If other schools that are on our ranks can charge way less, then obviously they have a better system where they’re being honest.”

As much as Wynne looks forward to graduation, she won’t walk the stage without wondering why SMU didn’t tell her what it did with the thousands of dollars she paid in fees each year.

“I can’t think of any security issues,” she said. “I can’t think of any reason why other than that they have some reasons to hide it.”