Lit fest focuses on American race relations

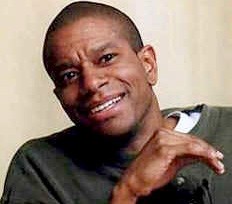

It’s hard to believe that Paul Beatty – a man who has built hisliterary career on scrutinizing the Lethal-Weapon-Bill -Cosby-It’s-a-small-freakin’-world-after-all depictions of American racerelations in popular culture – claims to have received theinspiration for his life’s only goal from a movie aboutmiddle-class white teenagers.

“I don’t want to sell anything, buy anything, or processanything as a career. You know, as a career, I don’t want to dothat,” said Lloyd Dobler in Cameron Crowe’s Say Anything.

And if you take Beatty’s words at face value, his own youth inLos Angeles and much of his undergraduate career in Boston werespent with the same lack of direction as John Cusack’s Dobler.

“I have one goal; it’s pretty small,” Dobler said. “No tie andno alarm clock.”

As an unusual layer of sleet pelted the Hilltop, Beatty, a thin,wiry man sat hunched over in front of a small crowd ofundergraduates. He read excerpts from his poetry and other writtenwork Monday night as part of Program Council’s LiteraryFestival.

His works, which include the novels The White Boy Shuffle andTuff as well as the poetry collection, Joker, Joker, Deuce,exploded into modern literary circles with their fluid andunrestricted voices and their frankness regarding the hypocrisy ofmodern America’s obsession with “multiculturalism.”

Deemed as everything from the “bard of hip-hop” to a “’90sRichard Pryor peaking ecstatically on acid,” Beatty’s gift lies inhis eye for the cracks in the American fa�ade of politicalcorrectness. His writing is a mile-a-minute beat bop of pop-cultureallusions, classical references, subtle jabs and stereotypeevisceration.

The gathered undergraduates, with thirsty looks on their faces,turned eyes in reference to this firecracker style articulated bythe soft-spoken man. But with students lounging casually on thesofas of the Hughes-Trigg basement, eating up line aftercynically-laced line, the scene appeared almost a parody of itself.The only thing keeping this from the very oh-so-trendy spoken wordreading that Beatty lambasted in one of his readings was the whirof beans grinding in the background and a few yuppies sporting thelatest J. Crew fashions and slurpingdouble-tall-trendy-but-not-too-picky lattes dotting the room.

After his reading, Beatty appreciatively took questions from theaudience. While fielding softball pitches like “Why did you decideto become a writer?” and “What’s the hardest thing about writing?,”he answered each question seriously and talked to his audience indown-to-earth honesty. But at the same time, a detached look in thelaid-back man’s eyes seemed to laugh at the scene playing out withhim at its center. For a man that claims to not take his writingtoo seriously, to be questioned like this must somehow have seemedlike a joke.

“I hate writing,” he said in response to one question. “I kindof write now because I have to. I f—ed up and became awriter.”

Because of this same unattached nature in his writing, somereviewers have been critical of Beatty’s work.

“I like to be contrary,” he said. “Once people expect somethingfrom me, I don’t like to do it anymore. And that’s not always agood thing.”

In his novel, The White Boy Shuffle, Beatty tells the story ofGunnar Kaufman, a black surfer bum who grew up in Santa Monica onlyto be repositioned in urban West Los Angeles because his motherfears he’s not growing up black enough. Over the course of hisearly life, Kaufman is able to adapt to both worlds. He’s anexceptional basketball player, a talent that eventually earns him aspot in college in Boston. But he’s also clever poet in much thesame style as Beatty himself, an ability that eventually earns himthe spot as the reluctant messiah of the black community.

And in response to the challenge of living on both sides of theracial divide, Kaufman only has one answer: “Why suffer the slowdeaths of toxic addiction and the American work ethic when theimmediate gratification of suicide awaits? It will be theEmancipation Disintegration.”

Critics have pointed to this nihilistic attitude in chargingBeatty with dealing irresponsibly with issues of racism in America.They claim that he has given up the fight for equality in exchangefor cynical jokes hurled at anyone involved in racial politics.

Beatty’s approach to American race relations is a lot like hischaracter’s approach to fitting in amongst both black and whitecultures. His criticism of America’s racial outlook seems to haveonly a dislodged morality to it. (Beatty himself claims to have afascination with Japanese culture on a “racist exploratory” level.)His appreciation for the small dents in the American melting potcarries its weight only through implication.

But through his humor, whites are able to cynically laugh at thefoibles of their often pathetic attempts to reach out to blacks,and they are offered a shroud of humorous self-hatred in which toconsole their progress over the last century.

The proof of Beatty’s sketch of the American multiculturallandscape lies in the nation’s reaction to his fame. His”it’s-funny-because-it’s-true” reputation has launched Beatty’sliterary celebrity on much the same path as his character,Gunnar.

After writing The White Boy Shuffle, Beatty recalls being askedto work as a consultant on the movie Bulworth with Warren Beatty.After reluctantly accepting the job, Paul Beatty was flown to LosAngeles and asked to read over the working draft of thescreenplay.

“It was like a 1920s Amos and Andy story,” he said. “It wasfilled with these ‘Yes, massah. I’ma commin’, massah’characters.”

After three days of failed writing attempts with a team of allwhite screenwriters, he finally called Warren Beatty inprotest.

“I said ‘So, I’m just the nigger screenwriter that makes it OKto have all these niggers in your movie,'” he said. “[WarrenBeatty] was like ‘Exactly!'”

He quit the project, but in his retelling to the students curledup before him Beatty seemed to take it all in stride. Thisdisconnected view toward everyday racism, writing and life throughwhich he is able to describe the world is what makes his acute eyefor detail.

An eye that can look at all that’s wrong in the world, shrug itoff and, like the poem with which Beatty ends The White BoyShuffle, remember the more important things in life:

“Like the good Reverend King

I too “have a dream,”

But when I wake up

I forget it and

Remember I’m running late for work.”