Living a lie

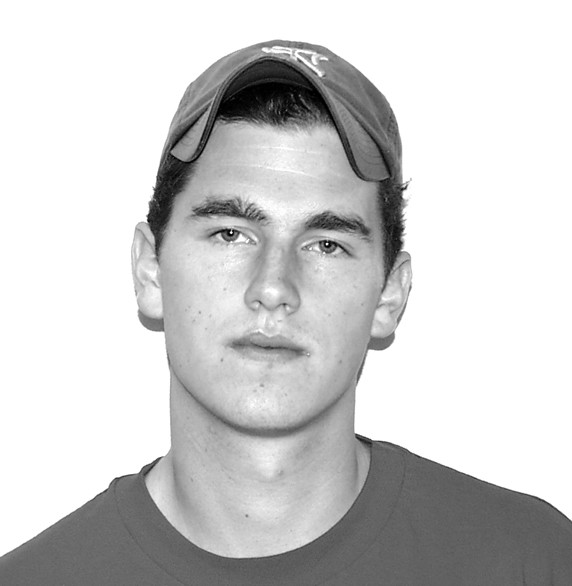

At the end of the spring semester of my junior year, I was voted student body president of my preppy, all boys’ Catholic high school in North Dallas. I remember sitting outside the library while the election committee made their official count of the votes. I was so nervous; I just sat there, Indian-style, in my navy blue coat and khaki pants, my fresh crew cut and new Cole Haans.

When the door to the library opened at 5 o’clock and Michael Larson came running towards me yelling, “You did it! You won!” I nearly fainted.

I remember leaning back against the brick wall separating me from “The Prayer Garden” and closing my eyes. I had done it.

I had tricked all those acne-ridden dweebs and nerds and jocks into voting for me. I had fooled more than half of the entire school into making me student body president. I had done it. I had succeeded. I could wear my ring now.

High school student council elections, as the movie Election made famous a few years ago, entail a whole lot of commotion and drama over something that, in all honesty, means absolutely nothing. My experience was no different.

The rumours began the following day. I was sitting in chemistry class when, from a few rows behind me, I heard, “Yeah, I think Mr. D– rigged the election. There’s no way Moses won.” I had to hold myself back from taking a Bunsen burner and setting whoever-it-was on fire.

Mr. D-, as you may have guessed, was the ever-unpopular student council advisor. Mr. D– had a weird, chili-bowl kind of haircut that was combed as if to depict a tsunami crashing into his head. Mr. D– wasn’t mean, but his love for catching unsuspecting freshman with their top button unbuttoned and his obsession with Looney Tunes neckties allowed for a variety of comments from teenage boys: “Man, if we have to read Canterbury Tales one more time, I swear I’m gonna go over to D–‘s house and rip the buttons off of all his shirts,” among other things.

As the week went on, the rumours got worse. Everyone, even the people who voted for me, even my friends started questioning the legitimacy of my recent election.

I could barely walk around school without being stared at or whispered about behind my back.

Yet, while all this was going on, while the entire school seemed to be planning a coup d’é#233;tat, I really didn’t care. In the beginning, of course, I was angry, but I knew it would fade away. I knew this sort of thing probably happened every year at every school in the United States. I wasn’t special; kids were just bastards.

While the rest of the school thought I was living one lie, I, in reality, was living another.

I had not cheated in any way, I had not paid off the election committee, and I had especially not done what some of my more imaginative peers said I had done to Mr. D-. I had, however, lied on my senior ring order form.

Exactly two days before the election, I turned in my Josten’s form stating what kind of stone, what kind of metal and which symbols were to be placed on my senior ring.

I did not want to place my school’s crest, which depicted a Texas “Ranger” riding a bucking horse, and I did not want the logo for automotive repair. Though I had not been elected president yet, I chose it anyway.

I remember how terrible I felt when the lady from Josten’s looked over my form and asked, “Wow, you’re the student council president?”

And I, ashamed of my own audacity, lied and said yes. Luckily, two days later, I was.