Colleen McCain Nelson had no reason to believe that April 12, 2010 would be different than any other Monday.

At the time, McCain Nelson was on the editorial board of The Dallas Morning News, and her husband, Eric Nelson, was serving as the assistant editor of the paper’s Metropolitan section. The two were on their way to work together that morning, and while she was checking her phone, she noticed it was the day of the Pulitzer Prize announcements.

“I mentioned to my husband, Eric, I said, ‘Oh, today is Pulitzer day,’” McCain Nelson recounted. “He said, ‘Oh,’ and then we started talking about what we might have for dinner that night.”

She had no idea that just hours later, she would win a Pulitzer of her own for her work on the paper’s Dallas North-South Gap project.

“The whole thing was just surreal,” McCain Nelson said. “Nothing can really prepare you for that moment.”

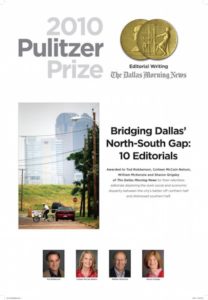

William McKenzie and Tod Robberson were also part of the editorial team working on the project, and won Pulitzers alongside McCain Nelson in the editorial writing category. Though their win was a huge success for The Dallas Morning News, the prize was only the most recent in a long history of Pulitzers won by papers in the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

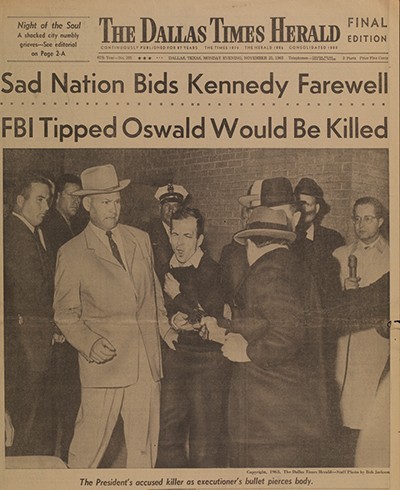

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Pulitzer Prizes. Photographer Bob Jackson, an SMU alumnus, won Dallas’ first Pulitzer in 1964 for his iconic photo of Lee Harvey Oswald’s assassination while with The Dallas Times Herald. The paper went on to receive two more Pulitzers until its final printing in 1991. Since Jackson’s win, The Dallas Morning News has won nine awards and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram has won two.

The Dallas North-South Gap Project

McCain Nelson, now a White House correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, began the project with the editorial board of The Dallas Morning News in 2007. Under the guidance of Sharon Grigsby, the deputy editorial page editor at the time, the board began its research on the disparities between both ends of the city, speaking to community leaders and combing through the streets of southern Dallas.

“We spent a couple months before we ever wrote a word just listening, and just trying to understand all the complexities of the challenges in these neighborhoods,” McCain Nelson said.

Throughout the project, McKenzie, now the editorial director for the George W. Bush Presidential Center, centered his work in Oak Cliff, focusing on economic development, education, and group homes for mentally disabled individuals. He said the series on group homes resonated with him the most “because there was a real, deep-seated problem there.”

During her time working on the project, McCain Nelson wrote a long essay about an afterschool program in one of the rougher neighborhoods of Dallas. The program not only benefited students, but also helped some of their parents, assisting them with finding jobs and learning to be teachers. She became especially friendly with one of the mothers involved, and was able to use her story in the essay.

A year after writing the essay, McCain Nelson read about the woman’s murder in The Dallas Morning News. She had been shot in her car.

“It broke my heart because she was doing all the right things,” McCain Nelson said. “The story had really meant a lot to me, and she had meant a lot to me.”

The Dallas Morning News’ First Pulitzer

Though McKenzie, McCain Nelson and Robberson won The Dallas Morning News’ most recent Pulitzer for their work involving poverty in Dallas, economic disparity was also the topic that won the paper its first Pulitzer in 1986 for national reporting.

That year, Craig Flournoy and George Rodrigue, a two-time Pulitzer winner, were honored for their eight-part series on segregation in public and subsidized housing, initially focusing on east Texas.

Throughout the series, Flournoy and Rodrigue spoke to many people involved with the system, from a housing administrator in east Texas who believed that “race mixing” was against the Bible, to developers who had goals of zero percent minority tenants despite the government’s obligation to fund racially diverse housing projects.

“There were very few projects that didn’t qualify as being segregated,” Rodrigue, now the editor of The Plain Dealer in Cleveland, said of housing projects across the country at the time.

After their series was published, the federal government took steps to eliminate discrimination in the housing system.

Though Flournoy, a former SMU journalism professor who now teaches at the University of Cincinnati, isn’t sure how much impact their project had on prompting the changes, he realized that he had found his calling in reporting on low-income housing and race.

“If you really want to make an impact, the more specific the area covered, the more you’re likely to make an impact,” Flournoy said.

Rodrigue went on to join a team of Dallas Morning News reporters and photojournalists who shared the 1994 Pulitzer for international reporting for their series examining the epidemic of violence against women across the world.

The paper won a Pulitzer again in 1989 for explanatory journalism for a report on an airplane crash and its implications for air safety. It also won the 1992 Pulitzer for investigative reporting after publishing a series charging Texas police with misconduct and abuses of power.

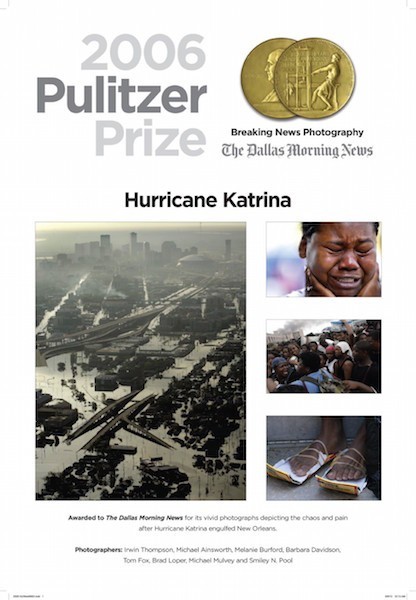

Four Pulitzers for Photojournalism

Though five of The Dallas Morning News’ nine Pulitzers have been won for reporting, four have involved the work of the paper’s photojournalists.

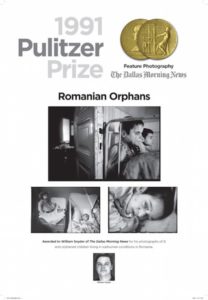

William Snyder, now a professor and chair of the photojournalism program at the Rochester Institute of Technology, won four Pulitzers during his time at the paper. He was first awarded the prize in 1989 for his work on a 1986 plane crash, and won again in 1993 for shooting the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. But he considers the photos he took of Romanian orphans, which he won for in 1991, his most important work.

“I tried to make the pictures as awful as I could,” Snyder said. “There was no way I could get across what it smelled like, or what it sounded like, or what it felt like, but I tried to really bother people.”

After years of shooting his own work, Snyder, while serving as the paper’s director of photography, guided The Dallas Morning News’ photojournalists in coverage of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Irwin Thompson, the deputy director of photography at the Dallas Morning News, was one of the photojournalists on the scene in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina struck. He won the Pulitzer alongside Snyder in 2006.

It took Thompson 13 hours to reach the outskirts of the city, a few days to actually enter New Orleans, and some strategizing to make his way onto a boat in the city’s Ninth Ward to photograph the aftermath. It was then that he said he became a “part-time journalist and rescuer” as he helped others in need get on board the boat.

Though the scene in New Orleans was tragic, Thompson explained that being behind the camera allowed him to desensitize himself to the situation, snapping photos and keeping his emotions at bay until it was time to edit.

“You use the camera as a mask,” Thompson said.

The Fort Worth Star-Telegram

The Fort-Worth Star-Telegram has been another important player in the coverage of Dallas-Fort Worth news since its inception in 1909, after the merger of the Fort Worth Star and the Fort Worth Telegram.

The paper won its first Pulitzer in 1981 for Larry Price’s photographs of the 1980 coup d’état in Liberia and its second in 1985 for Mark Thompson’s work on revealing a flaw in Bell Helicopter’s crafts that led to the deaths of hundreds of U.S. servicemen.

Thompson, who is now a correspondent at Time Magazine, worked remotely in Washington throughout his time at the Star-Telegram. After a few years of covering helicopters, he began to notice a trend in accidents in which Bell’s helicopters would fall out of the sky, like “a brick,” after dying midair. Despite the mechanical issues and no survivors, the solution was to teach pilots to fly safer.

After the deaths of more than 200 servicemen, one man, Larry Higgins, finally survived. Though it took some time to find the initially unnamed survivor,Thompson got the first interview with Higgins.

“I wanted him to say, as a survivor, that ‘Neither me nor my copilot was doing anything wrong. The motor blade came through the cockpit,’” Thompson said. “And that’s what he said.”

After Thompson’s five-part series was published, John Wickham, the U.S. Army chief of staff at the time, launched an investigation that led to grounding of more than 600 helicopters for maintenance.

“To me that was better than winning a Pulitzer,” Thompson said.

Though all of the Pulitzer winners expressed their gratitude for winning their awards, many echoed similar sentiments.

“It was an honor to participate in the project, an honor to win,” McKenzie said. “But it really is about the people you’re writing about. Because it’s their lives.”