Trip revisits Holocaust

Is it constructive to preserve sites where killing and suffering took place, no matter how gruesome the evidence might be?

Is it fair to exacerbate the collective shame some feel, even though they had nothing to do with an ignominious act associated with their hometown? Is that why it took 26 years following the Kennedy assassination to open the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza?

For the grieving relatives of the victims, is it better to bury all the grim reminders that haunt them? Or is it disrespectful to eradicate anything they feel memorializes their lost ones?

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day, PBS broadcast a graphic, disturbing documentary, “The Murder of Emmett Till.” Till, a 14-year-old from Chicago who was visiting relatives in Money, Miss. in the summer of 1955, was brutally murdered because he whistled at a white woman.

Instead of hiding the maimed remains of her son – he had one ear torn off, an eye gouged out, and a bullet hole in his head – his mother Mamie Till Mobley encouraged Jet magazine to publish the gut-wrenching photo of Emmett for all to see. She insisted on keeping the lid of her son’s coffin open, and she held off the burial for four days so the 50,000 people who came to Chicago to pay their respects could see.

“I wanted the world to see what I had seen,” she said. One hundred days later, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white person in Montgomery, Ala. Till and Parks ignited the civil rights movement .

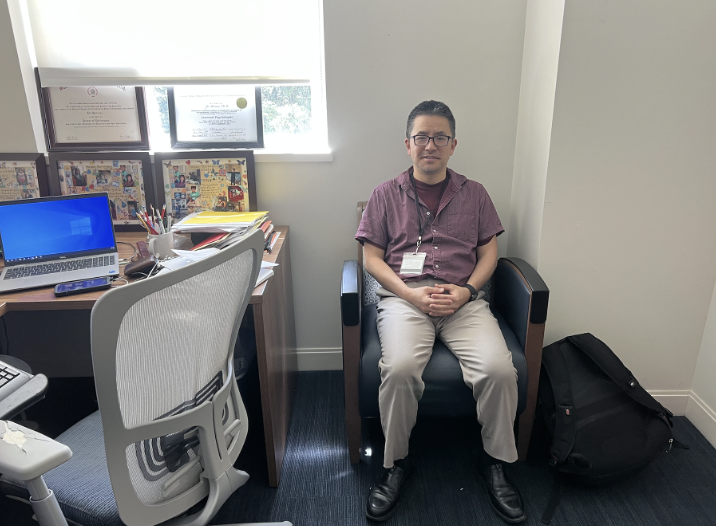

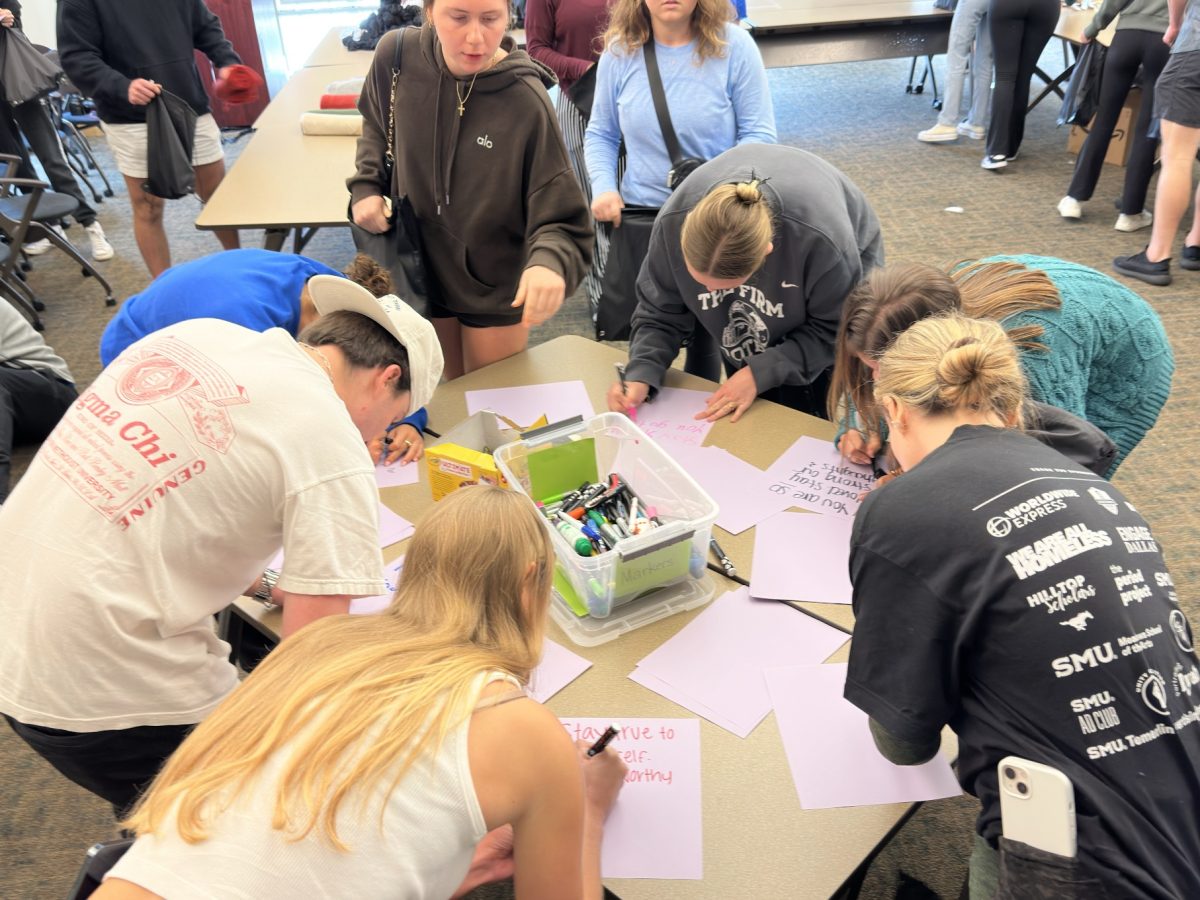

During the week of Christmas, my wife and I accompanied SMU human rights instructor Rick Halperin and seven other faculty and staff to see the remains of what Jews had seen in Poland during Wold War II. The ethnic cleansing began just 14 years before Emmett Till’s body was fished out of the Tallahatchie River with a 75-pound cotton-gin fan tied around his neck with barbed wire.

Unlike German concentration camps such as Dachau, Buchenwald, and Bergen-Belsen, the Polish death camps existed solely to provide the means to complete Hitler’s “Final Solution” of wiping Jews off the face of the earth. With frightening precision, the Nazis’ three-year blitzkrieg of murder in Poland killed almost as many Jews as the entire population of the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex.

Our group trudged alone on the snow-covered grounds of the desolate camps in Eastern Poland – Treblinka II, Sobibor, Majdanek, and Belzec. Conversation seemed out of place. For the most part, we did not share our thoughts and emotions until long after we had departed each camp.

After experiencing the more commercialized atmosphere at two well-known death camps – Auschwitz and Birkenau – we realized that Halperin made a wise choice to expose us to the other four camps where the solitude and serenity magnified the impact immensely. While we contemplated how the Nazis could possibly have killed 8,000 people a day, other visitors at Auschwitz chatted on their cell phones.

Halperin constantly took photos to use in his class. I asked how his SMU students reacted when he discussed the Polish death camps. He said that 90 percent of them wanted to know why they had never heard of these places.

That’s why it’s important to keep the coffin lids open.

If we do not preserve sites of infamy, if we do not build monuments and museums to show what happened and to honor both the survivors and the deceased, we commit a disservice to those who do not know the truth as well as to those who do. If we allow all the physical remains to deteriorate and fail to provide some sort of remembrance, we dishonor those who perished and perpetuate the anonymity and deception of the perpetrators.

In Poland, the Nazis tried to eliminate all traces of their deeds. They succeeded at Treblinka and Belzec. The Nazis actually built farmhouses, plowed the land, and planted trees and crops to disguise those areas. Former Ukrainian police guards at the camps took care of the “farms.”

Majdanek, on the other hand, still looks as though the Nazis left in a hurry the night before. All the macabre tools they used to kill and burn Jews are still there, remarkably undamaged by time – the “shower heads” in the gas chambers, the ovens in the crematorium, the truck chassis on which they burned Jews before the crematorium was built, the table used to extract gold and silver from the teeth of corpses, the guard towers, the double rows of electrical wire fences, even unused canisters of Cyclon B gas the Nazi guards dropped through holes in the ceilings of the gas chambers. Beyond the remaining barracks, a domed structure loomed ominously on the horizon. Close up it was a chilling sight – a mausoleum covering the ashes of 300,000.

I am grateful to those responsible for leaving everything as it was at Majdanek and maintaining it for 60 years. They even keep it open on December 25. I had never heard of the place before, but I will never forget it.

Treblinka, where 800,000 perished, also left an indelible impression on me. This was the final resting place for most of the Jews in the Warsaw ghetto.

After walking through the woods past memorial plaques, we entered the camp through the same spot where deported Jews and others had been unloaded for their last train stop. Recreated railroad tracks stretched the length of a football field. We perused a detailed map of what Treblinka looked like in 1942-43, including, incredibly, a zoo for families of the German officers. After proceeding up a small incline, we stopped and gazed at an unforgettable scene – 17,000 stones of various shapes and sizes spread out over a huge open field. These represented all the towns that lost Jews and others at Treblinka. The names of some of the places were chiseled into the granite. Other stones were blank. A large monument had been built at the site of the gas chambers, and there was a smaller rock in front with the words “Never Again.”

The contrast between Treblinka and Belzec was depressing. Located on the border between Poland and Ukraine, Belzec has been called the “forgotten” camp even though 600,000 Jews, gypsies, and Polish gentiles were exterminated there in 1942.

The town is virtually devoid of anything that reveals Belzec’s notorious past . Only the dilapidated train station where Jews were unloaded from crammed freight cars, stripped, and marched to the gas chambers remains. Near the entrance to the site, we stumbled upon a snow-covered lump. The bouquet of plastic flowers on top suggested what was buried underneath. I learned later that it was block of granite that cited in Polish the number of people killed at Belzec and that another decaying memorial had been torn down. For 45 minutes, we wandered through the trees and paths searching for some confirmation that the Belzec death camp actually existed.

Finally, we found one sign of hope outside the home nearest to the granite block. The words “United States Memorial Holocaust Museum” stood out from the Polish. Halperin told us that the Museum and the Polish government had raised money to build a memorial and museum.

I said a silent prayer of thanks.