“On a scale of 1 to 10, how bad is your headache? Are you suffering from blurred vision? Do you feel nauseous? Does sound bother you?”

These were the questions that Dai’ja Thomas, a sophomore women’s basketball player for SMU, was asked two weeks ago. Thomas had hit her head on the court during one of SMU’s basketball games, and was promptly taken off the floor. She was diagnosed with a concussion before the final buzzer went off.

These are also the same questions and the same steps to diagnosing concussions across the U.S. and the world.

News coverage has put a spotlight on concussions in sports from pro to high school in recent years. Usually, the attention is focused on after-effects and symptoms of concussions. Now, an SMU professor is focusing on a new track: the process of diagnosing concussions.

Sushmita Purkayastha is a tenure track faculty member in the Department of Applied Physiology & Health Management. She is an assistant professor and her research interest is focused on cerebral blood flow regulation. She holds two master’s degrees and a doctorate, along with a completed research fellowship at Harvard.

“We know this is an understudied area. With other health problems, when the doctor suspects diabetes or hypertension, they don’t guess, they run objective tests to confirm the diagnosis. But that’s not the case with concussion – yet,” Purkayastha said.

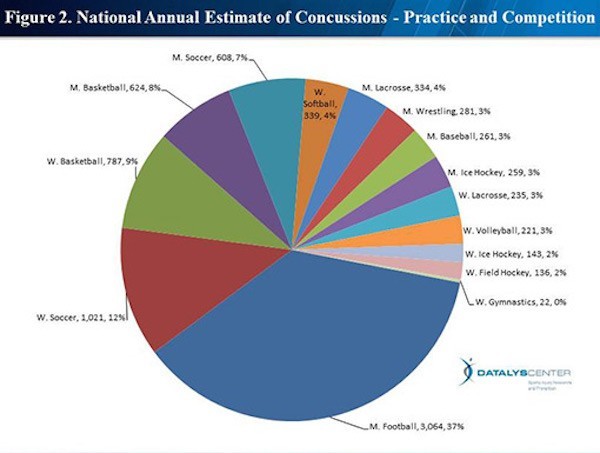

There are an estimated 1.6 to 3.8 million sports- and recreation-related concussions that happen in the United States each year, with the same kind of diagnosis process used that Thomas took part in. Finding out better “objective markers” in Professor Purkayastha’s mind could make huge waves in all competitive sports.

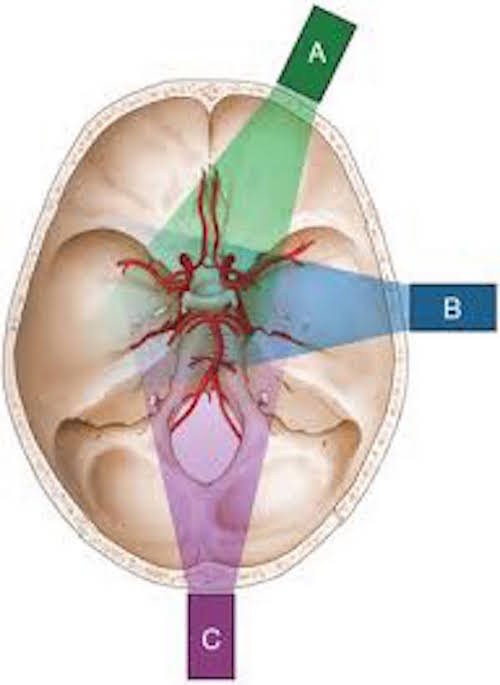

How is she doing this? Two words: Transcranial Doppler. Purkayastha is trying to determine objective biomarkers by focusing in on the brain’s blood flow regulation, instead of relying on the victim of a concussion to provide the diagnosis through a series of questions.

The Transcranial Doppler is placed on the head of both concussed athletes and non-concussed athletes to see if there is a difference in the amount of blood flow. Purkayastha’s hypothesis is that with impact, there is some kind of of interruption, and so in that area blood flow is compromised which causes the symptoms of a concussion.

To explain the process today, after a head injury occurs, the athlete is usually immediately showing signs of symptoms. Symptoms like mood change and fuzzy memory, along with more severe symptoms like vomiting and passing out, can all occur. Yet, there are also some cases where symptoms are not felt immediately, but even days after.

Usually, the trainer and/or doctor asks a list of questions to pinpoint what the victim is feeling, and from there decides whether or not to diagnose. If diagnosed, the athlete can be out anywhere from a few days to a couple weeks depending on the severity of the injury.

In the case of Dai’ja Thomas, finding a more concrete diagnosis could have been beneficial to getting her back on the floor faster. The process of answering questions day by day and taking a computer test held her back from competition.

“I honestly believe the protocol I took for my concussion could have been handled better than it was. I don’t feel like I should have had to sit out an entire week, before being able to actually play in a game,” Thomas said.

Professor Purkayastha agrees, saying the biggest benefit will be sports teams.

“If we find out better objective markers then we are not guessing, and there is going to be more discreet decisions on return to play and we can prevent secondary injuries. That’s huge,” Purkayastha said.

Thomas in fact took part of Purkayastha’s study, becoming one of 40 SMU student athletes that have decided to participate so far. The study looks at both athletes that have been concussed and also those that have had no head injuries, which Purkayastha said there has been about 20 athletes from each side come forward to help in the research. Each athlete that comes to Purkayastha is given payment for their time, for each of the three necessary visits.

In 2015, the first year that Purkayastha’s study was available, it was only focusing on SMU football players. After receiving a new one-year $150,000 pilot grant from UT Southwestern, it now is available for all student athletes on campus to participate.

“We have the money to do this pilot study, but we wanted to reach out to the athletes, and we just didn’t know how,” Purkayastha said.

The concussion study done by Purkayastha has been a huge centerfold for the SMU Research community, and also a big part of the Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education.

“The fact that she is able to do this and find another avenue to look at concussions is really a fantastic thing for Simmons and it really helps elevate a very fine program that already has terrific researchers,” Assistant Dean of the Simmons School Yolette Garcia said. “This is another tool in the toolkit that we can offer students which is a fantastic thing for us.”

The study is working off of a partnership with The Texas Institute for Brain Injury and Repair at the UT Southwestern Medical Center, also known as TIBIR. Purkayastha and others on the research team are expecting to have results by the Fall of 2015, with their goal to reach 200 tested male and female college athletes.

“This is the future of much more than just another million-dollar study,” Thomas said. “This is the next step into saving someone’s career, or that kid getting a full scholarship to play college ball, and even better, their life.”