The racist pamphlets found in SMU dorms in fall 2016 made Meron Metaferia, an SMU junior majoring in human rights, realize not only the prejudice on campus, but also people’s unwillingness to talk about it. During a discussion on current news in her political science class, Metaferia mentioned the pamphlets to spark a conversation on injustices in the SMU community.

“When I mentioned it, it was like pin-drop silent and nobody wanted to talk about it. The class just kept going on,” said Metaferia. “I brought it up because I thought, people in the class are geared towards making change in the world. It was a course about women, gender and world politics and I thought people were open-minded and always talking about injustices in other countries and what they can do to help. I wanted to bring it back to something happening in our own community and they did not seem very receptive to that.”

Situations like this inspired Maria Dixon Hall, an SMU communications professor, to lead an initiative in an effort to create a culturally intelligent campus.

“We are all walking around in these bubbles where we can see each other but we can only hear ourselves,” said Dixon. “So our job is to try and make sure that we have some straws in between the bubbles, so we can hear each other.”

Typically, when administrators and professors work to address issues of diversity, they aim for students to get along and value human differences. She says this goal is impractical with the current lack of cultural knowledge throughout campus. In an effort to change this factor, Dixon began the Cultural Intelligence Initiative, CIQ@SMU, effective Aug. 1, 2016.

“What cultural intelligence says is that, just like you and I have intellectual intelligence, where we can read a book, and we get smarter on a particular subject and continue to develop that skill and that knowledge,” said Dixon. “The same way can happen about cultures.”

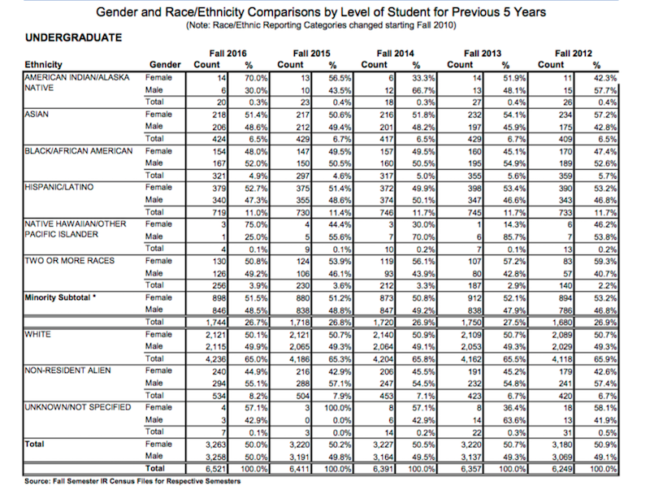

In the 2016-2017 SMU undergraduate student body, 26.7 percent of students are minorities. Some say the current efforts being made to unify the campus, though, do not provide students with the skills that can help address issues of diversity and inclusion on campus.

“I think that people just do not understand cultural differences,” said Will Hagens, a communications major and student leader for the initiative. “That’s not through anybody’s fault, but when our campus is as affluent as it is and as white as it is, it’s hard to understand other than what we know.”

Metaferia thinks people need to consider what makes people the way they are, and work to understand them.

“I don’t think its necessarily about people not caring, it’s about people not understanding, and not understanding the severity of the problem and how their silence and apathy can contribute to that issue.”

Hayley Halliburton, an SMU junior majoring in political science, emphasized the power and strength a person’s actions have on the reputation of a group.

“Sometimes people can feel victimized, offended or hurt by the discrimination or carelessness they have experienced from one or a few people,” says Halliburton. “It becomes easy to let that incident or those incidents speak for a larger majority who don’t carry those sentiments”

The initiative’s efforts are not limited to only spreading cultural intelligence about minority communities. The initiative leaders recognize that not everyone knows how to talk about whiteness.

“The way we typically talk about it is, we talk about white privilege,” said Dixon. “We don’t recognize that many students of color, whether they are African American, or whether they are Latino, Hispanic or Asian, have never really learned anything about whiteness other than what they see on television, what they have read on the news or what they have encountered in what I call ‘typical acts of micro-aggression.’”

Halliburton says her involvement with activities like Greek life, student senate, and intramural sports surrounds her with people of different races and culture. She says she has never been uncomfortable talking about race in class discussions, but there are definitely people who feel differently.

“I think that feeling uncomfortable when race is brought up may actually be part of the problem,” says Halliburton. “I feel like the day when no one, of any background, in a room feels uncomfortable when race is discussed is probably the day that race is no longer a social issue but rather just a fact of life.”

The initiative not only hopes to spread cultural intelligence, but also build and maintain relationships among different communities. Dixon says the initiative is planning on incorporating lessons into different PRW courses.

“We can create a college culture in which we know how to work, study and live together respectfully, and how to talk to each other and engage each other in a way that we can create shared meaning. For example: communicating,” says Dixon. “Because communicating does not happen until we have shared meaning.”

This communication is not just for students, but administration too. Danaysia Jones, a junior majoring in applied physiology and sports management, feels some professors do not know how to react when conversations come up involving race that make other students feel uncomfortable.

“Students will say how if they have something going back and forth between them and another student, because someone is being racially insensitive, the professor just doesn’t really say anything or address it,” says Jones. “They don’t really handle it.”

Jones talks about the vast potential professors have to influence their students, because their profession provides them with the opportunity to contribute to a student’s cultural knowledge.

“You’re the leader of the class. You are pouring into me. You’re a teacher, so that should be a part of your job,” says Jones. “Not only just teach me this material, but teach me how to be a person. Teach me to open my mind, that is what college is for.”

Micro-aggressive culture is formed through acts of unintentional and indirect discrimination. Jones blames this culture and unwillingness to learn for the racial insensitivity on campus.

“It’s just very much like ‘This is me. I’m me, and I don’t really care about you,’” says Jones. “I get this a lot being the only black girl in a lot of my classes. People will be like, ‘Oh your hair is so beautiful, let me touch your hair.’ I am not an animal. Don’t treat me like one.”

In an effort to help individuals find places of common language with one another, the initiative is going to teach different cultural languages in a series Dixon is calling “Ask Us Anything, Seriously.” Leaders in the initiative will survey the questions that people want to know about each other.

“I think people always have these kinds of questions in the back of their head but they are too afraid to ask because it’s the kind of question you are not really supposed to know the answer too,” said Hagens. “But, if we can’t ask uncomfortable questions we won’t ever go anywhere or learn anything.”

The series’ questions will be answered by members of those communities, and no set of questions is off limits.

“Everybody comes to college to learn something and not everything we learn is going to be a comfortable experience, but I think it’s still an important one,” said Hagens. “If you can learn the answers to those questions in a safe environment it reduces tension.”

Dixon’s motivation for the initiative came after working with the Oklahoma University SAE chapter after members of the fraternity were filmed chanting a racist hymn associated with the fraternity.

“The influence they had on me was the fact that they really didn’t know,” said Dixon. “We think they should have known, but this idea that ‘we do know’ when we don’t talk about as a society. We talk around it, we yell at each other, but we don’t provide each other the knowledge.”