by Jade Taylor

Women have historically been shut out from the male-dominated art world. However, Jenni Sorkin, art historian and associate professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, is interested in the post-war era, which is when female artists were carving a name for themselves in sculpture and ceramics.

“The history of post-war abstraction offers a different and important history of [women’s] prominence and inventiveness,” Jenni Sorkin told an audience of approximately 50 students and faculty in the Owens Art Center on Wednesday.

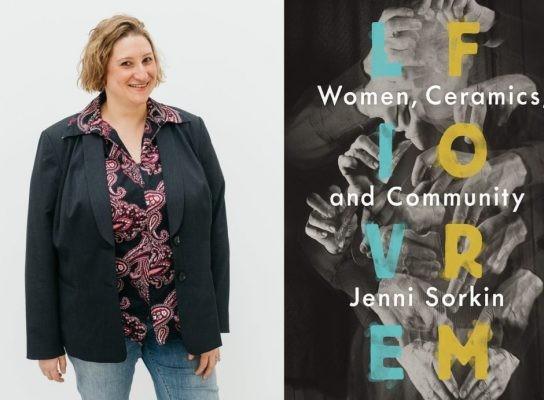

Sorkin studies the connection between gender, material culture, artistic labor and contemporary art. Her publications on the subject include “Live Form: Women, Ceramics and Community” and others. She is an award-winning art journalist who speaks as a critic and scholar at universities, museums and art galleries throughout the world.

“I invited her because she engages a whole group of sculpture practice that was very important to me when I was a graduate student,” sculpture professor and Division of Art chair Jay Sullivan said. “[Her lecture] was a restatement of feminist practice but also material practice; and the relationship between the hand, the eye and the experience, which is disappearing.”

Sorkin focused on pieces from the new Hauser Wirth & Schimmel gallery space in Los Angeles. She discussed various female artists like Ruth Asawa, Claire Frankenstein and Gego; the unique materials they used, their methods of construction and the finished artifact.

During the feminist era, women who were shut out of sculpture departments made sculptures anyway. In order to receive acknowledgement, some women would change their names when exhibiting, so their gender could not be identified.

Sorkin says her investment in women artists is permanent and continuous. She started studying women artists because art history is still largely taught from and by the men’s perspectives. She has worked on exhibits with the feminist revolution for numerous years and is well qualified.

“As a professor, in the classroom it is important to work across specializations and be a generalist,” Sorkin said. “As a writer and cultural producer, it is crucial to narrow in and create a specific argument. I work primarily on women artists across all media.”

The lecture was well received by the audience. Many liked that a discussion about history felt relevant in a world that continues grappling with sexuality, race, class and gender.

“It was a great lecture and I think her ideas were really fleshed out and the presentation flowed very well,” first-year MFA student Xavier Carter said. “The historical viewpoints were presented in a light that was very contemporary and at the same time showing the divisions of the past and the present.”

Sorkin said she is hopeful that the art world is moving toward not just gender parity, but also an even broader definition of equity.

“There is greater parity in the art world today than 50 years ago, but also much more awareness about inequities that are not just about gender, but about difference in many other ways: racial, ethnic, economic, etc.,” Sorkin said.