Imagine two drunk college students at a party. One student accuses the other of rape, but the accused believes he or she is innocent. How can the university handle the situation fairly?

“The system needs to be fair for all,” freshman Jared Rule said.

The way sexual assault is handled faced turbulence after U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos rescinded an Obama-era law. Critics said her order could make proving sexual assault on college campuses more difficult.

One in five women and one in 16 men report being sexually assaulted in college, according to the National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

Not On My Campus president Madeline Findlen believes the number could be higher in reality.

“Sexual assault incidences are already underreported, with only 20 percent of female student victims ages 18-24 reporting to law enforcement,” Findlen said.

Not On My Campus is a student-led movement to end sexual assault on college campuses. The program originated at SMU and has spread to other campuses.

In 2015, a study published in Violence Against Women found that false allegations of sexual assault are between two and 10 percent.

In 2011, the Obama administration changed guidelines under Title IX. The new guidelines allowed higher education to use the lowest standard of proof to decide whether a student is responsible for sexual assault.

DeVos’ new guidelines, however, allow colleges not to use those guidelines. DeVos’ guidelines use only “clear and convincing evidence” when deciding if a student is guilty of sexual assault.

DeVos’ guidelines are “a step in the right direction” and “appear to have good intentions,” freshman Ellie Diefenbach said.

But others believe taking away the protections put in place by the Obama administration is a setback.

DeVos’ guidelines are “a huge step backwards in changing this culture that subjects women to having to go to school in an environment where they are not protected from sexual harassment and violence,” said Dallas County Criminal Court judge Nancy Mulder, who has heard many sexual assault cases.

“While we and other universities wait to learn more from the Department of Education, it’s important to note that any changes in federal guidelines will not affect SMU’s commitment to prevent and end sexual misconduct,” said Vice President for Student Affairs K.C. Mmeje.

DeVos’ orders, issued in September, urge universities to take sexual assault behaviors seriously and continue to spend money on counseling. But DeVos also believes the rules need to be fair, which means creating a fair system for the accused.

“The process must also be fair and impartial, giving everyone more confidence in its outcomes,” DeVos said in a statement to the media.

Many students believe the system needs to treat both people in sexual assault situations with equality.

“The first step to gender equality is true gender equality,” senior Caelan Colburn said.

SMU has struggled in dealing with sexual assaults in the past.

A 2012 investigation by The Daily Campus uncovered more than 100 reports of sexual assault in 25 years. Police chief Richard Shafer could recall only one case in which suspects were successfully prosecuted since he joined the force in 1999.

Related: Former student sues SMU for mishandling 2012 sexual assault

During the fall 2017 semester, three cases of sexual assault were reported, according to SMU police records. One of those cases, as well as a case of forcible fondling, resulted in Title IX referrals. Two cases are still active.

Three forcible sex offenses were reported on the SMU campus in 2015 and eight forcible sex offenses on SMU’s main campus in 2016, according to the 2016 Annual Security and Fire Safety Report.

Three forcible sex offenses on campus were not reported to the police but were reported to other campus officials in 2014. In 2016, six forcible sex offenses on campus were reported to officials, but not to the police. The statistics show that both forcible sex offenses reported and not reported to the police have increased over the last year.

Related: What happens next? Uncovering the problematic issues behind reporting sexual assault

“SMU students will be alerted of any changes to university policy,” Student Senate president David Shirzad said.

Findlen said that regardless of policy changes, people should not stop the momentum against sexual assault on college campuses, including social media movements, programs to educate people about the issues and safety awareness.

“We do not want to lose the progress we are making,” Findlen said.

Findlen encourages students to raise awareness of sexual assault and attend future Not On My Campus events. The group distributes information on campus, even at football games, and accepts donations.

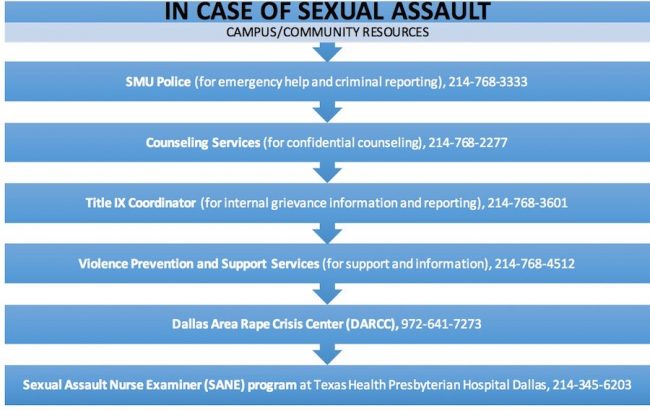

Students should be aware of SMU’s crime prevention procedures. Emergency blue-light phones across campus connect directly to the SMU police. Students can also download the app Tapride, a safety escort service that gives students free rides 7 p.m. to 3 a.m daily.