Every Thursday night at 5:30, a group of students gather in the cafeteria of Sam Tasby Middle School. They laugh and eat home-cooked food together. Bits and pieces of conversations in Nepali, Burmese, Spanish, and a variety of other languages echo from every corner of the room. The conversations are soon drowned out by a commanding voice speaking into a microphone, and the kids quickly turn quiet.

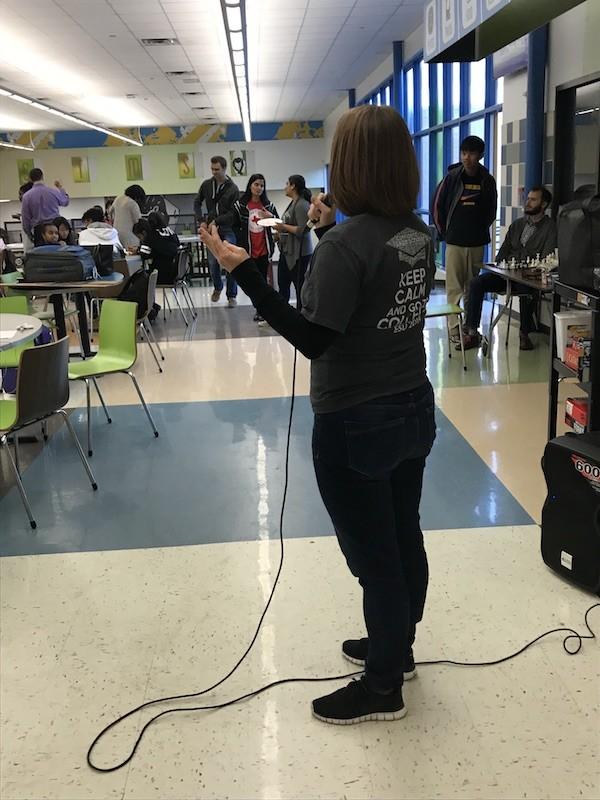

A woman stands at the front of the room, speaking to the students while using her feet to untangle herself from the long microphone cord wrapped around her legs. The back of her shirt reads “keep calm and go to college.” At the end of the night, she leads the room full of students to recite a mantra:

“Where we come from makes us unique. We have the potential to climb any peak. Everyday life presents new opportunity. Inspiration is the key to find our own individuality. Perseverance is the skill that we posses. We are designed for greatness, we expect nothing less. We realized our potential, pushed with perseverance, became inspired, and now we’re ready to lead our hearts on fire”

This is Janet Morrison, the director of the EAGLE Scholars program, an after-school college readiness program for 7th through 12th graders in the Vickery Meadow neighborhood, which is home to a diverse immigrant and refugee community in Dallas.

“Our program focuses on college, career, and culture with the goal of assisting each of our Scholars in becoming a well-rounded, knowledgeable individual who is prepared for college and beyond,” says Morrison, who has been with the EAGLE Scholars for six years.

Sam Tasby Middle School is a fitting location, named after the man largely responsible for the desegregation of Dallas ISD schools in 2003. Tasby, who wanted to provide his black sons with the same education as their white peers, fought to give marginalized children the same opportunities to succeed. It is a mission now being carried out by community leaders like Morrison.

“I’ve always enjoyed working with children,” Morrison says. Her interest in education began as an adult when she moved into a new community and became close with the children there. Before she knew it, her apartment had became the location of a pseudo after-school program.

She recounts a moment she regards as especially transformative in her life. “A 5th grader who came to my apartment couldn’t read. When I went to the school and asked the assistant principal why, she told me, ‘Maybe he has reached his peak.’” It was that comment that led Morrison to go back to school and continue to get a doctorate in Education.

“I came to realize that kids rise to your expectations–and that people had low expectations–especially of children in low-income communities.”

She has found that many children deal with circumstances beyond their control that made it significantly harder for them to meet their potential. “The system isn’t set up for socioeconomically disadvantaged students. It works against them and still expects the same outcome,” Morrison says, noting that families who struggle with barriers in language, income, access to transportation and experience find it incredibly difficult to even navigate that system.

In Morrison’s experience, the system allows for the hard work and academic success of a student to be undermined by their circumstances. In one instance, an EAGLE scholar was accepted into one of most prestigious magnet schools in the district, but because of a lack students in her area, the bus would not pick her up. With a working father and brother, and a mother in school, she had an additional financial burden on her family. This student was also a person of color who felt isolated and out of place in that environment. By the third day of school, she had left.

Morrison said one of the hardest parts of her job is watching students face the inequity of our society.

“Many times the injustices are so ingrained in our system, they don’t even know they’re facing the it.”

Helping the EAGLE scholars is not the only way Morrison hopes to actively combat injustice. She believes that through the program, she can equip her students to do the same.

“I have learned that my role is often being an advocate for our students, and encouraging them to be an advocate for themselves”

Morrison undeniably plays an essential role in the lives of each scholar, but they play a significant role in her life as well.

“I love learning from them, engaging with their families, hearing their parents’ hopes and dreams for their children, and being able to interact with a large number of cultures, religions, and languages,” she says.

Unfortunately, her passion and hard work is not enough to transform a system that marginalizes many children in the Vickery Meadow area. Every year, the program can only accept around 60 new middle schoolers, which is just half of the usual number of applicants. For many of the children living in the area, becoming an EAGLE scholar is the best chance they have at pursuing higher education.

“One of the worst parts is knowing we don’t have the funding or capacity to take more students,” Morrison says, highlighting the reality that the EAGLE scholars program can only go so far without the cooperation of the community.

“Funding is always a huge need. We also love connecting with companies and individuals who can help us do unique and creative field trips to expose our Scholars to 21st Century skills needed in the workplace,” she says.

A large part of the program relies on volunteers, many of whom are SMU students. One of them, Cristina Reyna, has been volunteering for two semesters now. She was introduced to the program through Professor Rick Halperin’s Human Rights class.

“Every week I went to EAGLE Scholars with a smile on my face because I knew I would be helping these students,” Reyna says. “But also because we would all have homemade samosas and enchiladas for dinner.”