Camp destiny

Nestled in the silent Davis Mountains of west Texas, it’s easy to forget about the madness and clamor of the world. Drowsy white clouds hover in an empty blue sky. The smell of campfires and the sharp cries of brave grassland birds all melt together in the crystal sunlight. Intrepid settlers who tested this land in centuries past must have bowed to its aridity and its majestic danger. Only slowly, with the help of expedient plumbing and endless tracks of asphalt has civilization begun to inch onto this fresh, rugged corner of Earth’s face. A well-situated observatory, a ranch and a state park dot the otherwise untouched mountainsides as evidence of the gentle trickle of modern life.

We have a steady morsel of dirt on which to assemble our tent. We have a carful of sleeping bags, energy bars, flashlights, bottled water and other camping essentials. We have just enough daylight left to coax a dancing fire from a pile of sticks. We have a sky splattered with dazzling stars waiting to make its entrance at nightfall. Life in the mountains feels like a deep, idyllic dream.

The primeval appeal of the wilderness has pulled humanity toward its warm, mysterious belly since the first echoes of our cosmic memory. The terrifying beauty of the land, the volatile elements and the journey that is survival coalesced to shape us into the weird and wonderful species we are. There’s a reason why in the spring of 2003, I feel more at home asleep under a tree I’ve never seen before than I do driving in the city where I’ve lived all my life. We are built of the heavy mud, the swollen river water, the pristine air, the vicious tree limbs and the violent rain that stretched our lungs and polished our muscles for thousands of years to bring us here.

There’s an argument against ending human suffering that goes something like this: if we cure diseases and feed everyone and stop killing each other, life will be boring and we won’t appreciate our good fortune. It takes darkness to understand light, there’s no good without the bad, etc., etc. To an extent I agree that life requires some tribulation to be both interesting and worthwhile. However, war and starvation seem somewhat excessive levels of comparison. Were Mickey Mouse to be elected totalitarian dictator of the world tomorrow and bring compulsory unfettered joy and laughter to all six billion of us world wide, there would still be plenty of strife for us to contend with. Even life in the placid Davis Mountains has its perils.

You may still be launched from your bike on a rocky trail and succeed in tenderly mangling some appendages as you land. You may still get stuck beneath the convergence of three brutal thunderstorms and have to sleep in a cold puddle. You might still unwittingly stumble over an unforgiving cactus while trying to get a better grip on your kite string. You may face the menacing wrath of a spooked Montezuma quail as it careens toward your head in an explosion of feathers.

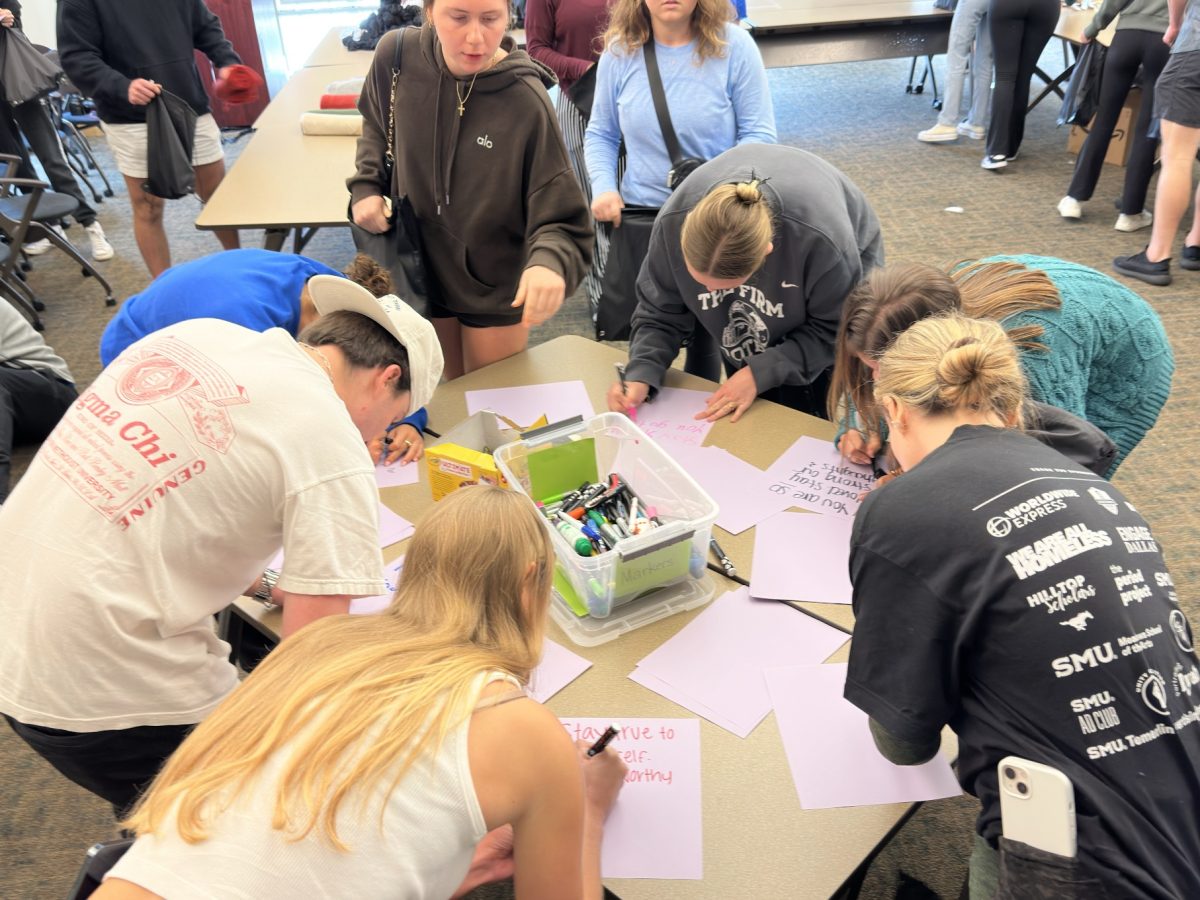

These ghastly hazards are mercifully tempered by the inherent benefits of camp life that, in my experience, occur exceptionally rarely in human dealings. Strangers offer firewood, whiskey, and stories of adventure expecting nothing in return. You are free to accept such gifts without the slightest apprehension of veiled motives or obligation. The darkness of nighttime feels safe, and prickly with the promise of adventure.

Back in the real world, global juggernauts bicker over the fate of a tiny, dying nation. Politics, bureaucracy and progress languish in the bitter stew of centuries of standard protocols. Somewhere along the path from tree climbing to nation building, the innovativeness and spontaneity that brought us out of the wild woods were subsumed by process and paperwork, by big guns and little hearts.

Maybe the flicker of harmonious existence hasn’t died in us yet. Like a campfire that ripples to life in the warmth of dusk, all it takes is time, encouragement and persistence. From the first hopeful sparks grow the healing flames that light up your modest patch of earth, and bathe the air in thick, fragrant smoke. We’re waiting for the brightness and the heat that will soothe the danger of the wilderness. In darkness we watch for the moonlight that will show us the way home.