Instinctively, he shakes her husband’s hand, Jennifer Collins recalls. “Nice to finally meet the Dean of the Dedman Law School,” the man says. His warm welcome is followed by an awkward silence.

Eventually, Collins corrects his assumption.

“I have had people say to me, ‘The Dean of what? The Dean of Admissions? The Dean of Career Services?’” Collins said. “And I say, ‘No, the Dean.’ They say, ‘No, no the Dean of what?’” They are sort of surprised that I am in the actual Deanship.”

Although women are as qualified as men, people expect leaders to be male because of underlying gender stereotypes.

SMU Women’s and Gender Studies Professor Joci Caldwell-Ryan said during the 1970s and 1980s, people knew that women were holding jobs, but there was still a huge pay gap between men and women in the United States.

“That’s when people began to say if things don’t change at the top they’re not going to change at the bottom,” Caldwell-Ryan said. “Since the 1990s on, there has been a focus on the problem of leadership.”

Women hold 57 percent of undergraduate degrees and 60 percent of master degrees according to the National Center for Education Statistics. Women also make up 47 percent of the labor force according to the United States Department of Labor. However, despite their education and equal participation in the labor force, women do not hold leadership positions at the same frequency as men.

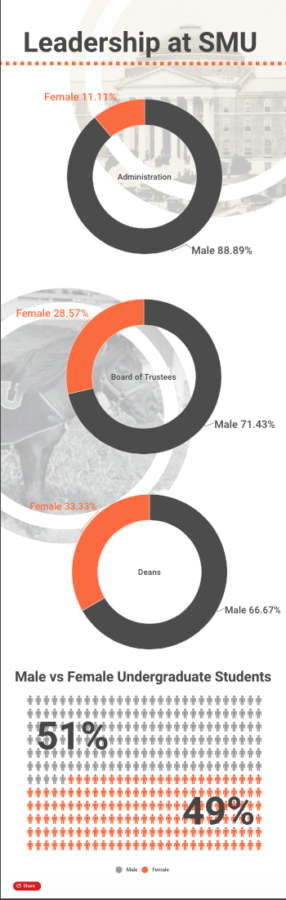

At SMU, women make up 28.5 percent of the board of trustees, 11 percent of the administration and 33 percent of the deans. They represent a school population that is 49 percent female.

At SMU, women make up 28.5 percent of the board of trustees, 11 percent of the administration and 33 percent of the deans. They represent a school population that is 49 percent female.

“It’s like there is this imaginary world of what should be, but the real world is that women do work,” Caldwell-Ryan said. “It really does come through is when you see in higher levels of leadership, when you see the percentage of CEOs.”

At S&P 500 companies, women make up 21 percent of board seats and 5 percent of CEOs according to the global nonprofit Catalyst. In the legal field, 22 percent are partners and 18 percent are equity partners according to the American Bar Association. Women hold 27 percent of presidencies of higher education institutions according to the American Council on Education.

Caldwell-Ryan said from the 1950s to 1970s women faced overt discrimination due to the lack of laws that protected women in the workplace. Although laws like Title VII or IX exist today, women still can face implicit bias or deep-rooted stereotypes.

“So, it is covert, it’s hard to see, it’s hard to fight. Because it’s almost invisible,” Caldwell-Ryan said. “I think those old stereotypes are there, but they are somewhat diminished.”

Caldwell-Ryan points out that employers would never ask if the job expectations would interfere with family life because that would be illegal; however, they still have the underlying assumption that women would more likely take family leave or need maternity leave.

“For a man to have a family, it is not a liability. It is a benefit. Now, not only is he a great leader, but he is a great family man too,” Caldwell-Ryan said. “That is the kind of asymmetry that really needs to be broken down.”

Collins understands this duality because she has three kids. She said schools tend to expect for the mothers to be there if their children are sick, participate in the school bake sales, and volunteer in the classroom. However, Collins said that women leaders can counter these expectations by splitting family responsibilities equally with spouses.

“You feel the double bind. Are you doing your work as well as you would like? Are you fulfilling your parenting role as well as you would like?” Collins said. “I think it can be challenging, and I have definitely felt those feelings.”

In an analysis of 69 studies on stereotypes from the Psychological Bulletin, researchers found that stereotypical male characteristics of independence, aggression, competitiveness, rationality, dominance and objectivity correlate with current expectations of leadership.

Before her educational career, Collins was a homicide prosecutor in Washington for about eight years.

“The homicide detectives used to love to come into my office to try to show me the grossest most horrific crime scene photos that they could find,” Collins said. “I think that was the way they were testing me to see if I was tough enough to handle the demands of the job.”

Women leaders of higher education reported that the main barriers of leadership are different expectations for men and women as well as lack of opportunity in a study conducted by Human Education Resource Services. Their research also showed that having women role models who exemplify leadership made these positions seem more attainable, attractive and weakened stereotypes.

“It might be that your male superior can mentor you about some things, but he’s not going to be able to mentor you about how it is to be a woman in a male-dominated field,” Caldwell-Ryan said.

Caldwell-Ryan said organizations like SMU’s WISE and Ignite offer the mentorship and nurturing that women need in order to reverse decades of cultural habit.

“It is all really positive and uplifting,” Caldwell-Ryan said. “It’s not about claiming victimhood status or anything like that.”

SMU Vice President of Business and Finance Chris Regis joined the Business and Women organization to meet people, learn from people, and expose herself to new things. In a Young Careerist competition, she had to give a speech that forced her to grow and mature.

“Confidence and being assertive can be viewed as a negative in women while it is viewed as a strength in males,” Regis said. “We need to focus on building confidence, encouraging them to go after opportunities and not shy away.”

Many women do not see themselves as women leaders, but just as leaders.

“I have been very fortunate to work for people who believe in me, whether I am a woman or not,” Regis said. “I think part of the reason is because I don’t see myself as any different, I don’t see myself as a female doing a job, I just see myself as a capable person doing a job.”

Research from Leadership Quarterly indicated that exposure to role models that counter stereotypes have been shown to reduce stereotypical thinking, increase creativity and problem solving. Professors from University of Wisconsin-Madison have found that programs of anti-bias education have helped reduce bias. Understanding implicit biases can help people undo them.

This is Collins’ fifth year as Dean of Dedman Law School. She said being a woman has been an advantage to her career because she is able to have empathy and compassion, yet she knows how to set the tone as a leader. She encourages women to stop doubting themselves and start applying for jobs, asking questions in meetings and volunteering for assignments that excite them.

“If someone says you should run for the president of your sorority or you should try to be the head of this campus club, you should listen to them because they are seeing something in you that you might not see in yourself but is actually in there,” Collins said.