Editor’s note: This story contains graphic descriptions of sexual assault.

An SMU freshman was standing outside of her sorority house in April of 2019 when she finally got the letter she had been anxiously waiting on for months.

Tears started to rush down her face as she began to read: “Investigators have determined that there is insufficient evidence…”

SMU would be taking no disciplinary action against the male student she claims raped her.

“I wouldn’t have gone through the process at all if I didn’t think I had some sort of fighting chance here,” the student said tearfully in an interview with The Daily Campus. “I really don’t understand what more I could’ve given them, unless they’re in the room while it happens.”

The student, now an SMU junior, did not want to be identified to protect her privacy. She fears that using her name could provoke a negative response from the university. When it comes to her legacy on campus, the Dedman student wants to be remembered for the things she’s done, rather than for what happened to her.

For months, the student said she was subjected to an invasive investigation by SMU’s Office of Institutional Access and Equity (IAE) that required her to relive her assault in front of insensitive university officials, all while continuing to live just steps away from her alleged rapist on campus.

This student is one of six SMU students whose sexual assault cases were examined in an investigation by The Daily Campus. Of the six, three students pursued a Title IX investigation after an alleged on-campus sexual assault, and each later received an ‘insufficient evidence’ finding. The three students who did not pursue an investigation, say they reached out to university officials seeking other forms of support, including medical attention and academic accommodations.

The students accuse SMU of not only mishandling their cases, but subjecting victims to a harsh and even traumatic process, and in some cases, expecting students to continue living in on-campus residence halls with their accused assailant.

The Daily Campus reached out to university officials to understand how many Title IX sexual assault investigations occur, and how common it is for them to conclude in an ‘insufficient evidence’ finding. Citing FERPA laws and student privacy concerns, the university did not provide the information.

Instead, student journalists were directed to the 2020 Annual Security and Fire Safety Report, which publishes campus crime statistics in compliance with the federal Clery Act, and lists 25 reported incidents of campus rape over the past three years. Title IX officials would not say how many of the 25 incidents in the Clery report were investigated through the Title IX office.

“Each case is different, but when the only evidence in the case is the statement of the complainant alleging guilt and the statement of the respondent alleging innocence, with no additional evidence to support the allegations of either party, it can be difficult to meet the preponderance of the evidence standard,” said SMU’s Title IX Coordinator Samantha Thomas in an email interview conducted through the university’s director of strategic communications.

SMU uses the ‘preponderance of evidence’ criteria for Title IX investigations. Essentially, this means evidence presented during the process only needs to show that an incident is more likely to have happened than not.

If ‘proof beyond a reasonable doubt’ is the highest burden of proof in our legal system, a ‘preponderance of the evidence’ is one of the lowest, says Dallas-based lawyer Michelle Simpson Tuegel.

“It really doesn’t require a lot, and that’s what is really troubling to me about these schools saying there is insufficient evidence,” Tuegel said in an interview with The Daily Campus. “What I think a lot of students are asking is, ‘what would be sufficient?’”

Tuegel is currently representing another SMU student who received the same ‘insufficient evidence’ finding last year, after reporting that she was raped by a 335-pound football player in her dorm.

Their lawsuit against SMU alleges that the university not only mishandled the Title IX investigation, but also allowed both students to continue living in the same residential building, where the female student was reportedly subject to harassment from the player and his teammates.

The university recently responded to the lawsuit in court, requesting the case be dismissed on the basis that “Title IX does not require flawless investigations,” and that the victim needed to demonstrate that the university practiced deliberate indifference to warrant legal action.

The Right Thing to Do

The student who did not want her name used in this story, is a Resident Assistant (RA) at a dorm, and a highly involved student leader on campus. She was extensively educated on the university’s policies regarding sexual misconduct due to her roles in campus programs and organizations. When she was assaulted, she knew exactly what she was supposed to do: report it to SMU’s Office of Institutional Access and Equity (IAE).

Even though she knew she should file a report, she couldn’t help but feel hesitant.

“I felt very much like it was my fault for putting myself in that situation, that I should have been smarter,” she said. “If I, as someone who had all of this education, and knew that it was the right thing to report, didn’t feel comfortable doing that, I just have to wonder what it’s like for other people who don’t have that same kind of education or experience.”

“If I, as someone who had all of this education, and knew that it was the right thing to report, didn’t feel comfortable doing that, I just have to wonder what it’s like for other people who don’t have that same kind of education or experience.”

Sean Woods, the primary prevention coordinator at the Dallas Area Rape and Crisis Center (DARCC), says sexual violence goes largely underreported due to the widespread stigma surrounding rape that essentially blames victims for what happens to them.

“There is this mentality about false reporting, especially on college campuses, that mainly women are coming forward with these false accusations, mostly towards men,” Woods said. “We know for a fact that is simply not the case, when only about 2 to 8 percent of all rape accusations are even false in the United States,” he said.

The student ultimately made the decision to file a report after making sure she had enough evidence for a strong case. She says she was never looking to get anyone in trouble, but believed that alerting campus officials was the responsible thing to do, especially if other students were potentially at risk.

She describes the incident that night as “painfully cliche.”

“I had way too much to drink, classic stuff,” she said. “I wasn’t watching my drink, so I don’t know if something happened there, because typically I can have about as much as I did and be okay. But I wasn’t.”

Looking back, the student believes a male student she had met at a party took advantage of her while she was clearly unable to consent. It’s unfortunately a common occurrence on college campuses across the country. Studies estimate that the number of college women who experience sexual assault could be as high as 1 in 5, and suggest that at least half involve alcohol consumption.

But unlike many students, this student, partially due to her knowledge and training as a student leader, was confident that she had enough evidence to prove to IAE investigators what had happened to her that night.

“Oh my God, I gave them so much. I gave them text messages between me and this person, I gave them all of my pictures and videos from that night, I told them everything I had to drink,” she said. “I did all of my research, I was so careful about looking up the correct terms and having everything prepared if I was going to go that route. And I did.”

The student says the Title IX process was cold and overly complicated. She recounts being uncomfortable detailing intimate and embarrassing details to an “unfriendly” male administrator, and being frustrated by a great deal of legalistic language and harsh questioning that she likened to an interrogation.

“Definitely not the most supportive or compassionate. It very much seemed like they had the interests of the university in mind,” she said.

Tuegel, a lawyer who has experience with Title IX legal work, says that’s a widespread problem across many college campuses.

“They stick a male Title IX employee or investigator in a room alone with a female student who’s been sexually assaulted by a male,” Tuegel said, “That’s not a best practice. That’s not sensitive.”

Woods works primarily in education and outreach for DARCC. He suggests the issue could be a lack of “trauma informed care,” by which universities may not be properly equipped to handle situations where individuals are likely traumatized by deeply emotionally distressing experiences.

Crying For Help

Kaili Wirth, a biology and economics major at SMU, says she experienced this kind of neglect from the university first hand after she says she was raped in her dorm by a male student during her freshman year.

Wirth, now a senior, accuses the student of intentionally getting her drunk to the point of incapacitation, and taking her back to her dorm in Kathy Crow Commons where he had unprotected, unconsensual sex with her. Wirth’s friends walked in on the two, and say they kicked the male student out of the room when they realized that Wirth was incoherent, hurt, and covered in her own vomit.

The next morning, Wirth woke up to find that her right leg was covered in a deep bruise. She says she remembers being so drunk the night before that, in her alleged assailant’s attempts to hoist her onto her bunk bed, she had fallen six feet to the ground and injured her leg.

After the incident, Wirth, only 18 at the time, made the decision to reach out for help by going to the Dr. Bob Smith Health Center on campus for support and medical attention. She had vaginal tearing, and says she knew not to shower or wash her clothes to preserve evidence.

When she got into the doctor’s office, Wirth broke into tears. She says she told the health center official what had happened and asked for a full STD panel and some sort of a rape kit, but the doctor discouraged her from pursuing it further.

“She was like, I don’t think we need to go full STD testing,” Wirth said. “She kept saying I didn’t want to report because what are the odds I would win? Because I was drinking.”

Dr. Randolph Jones, executive director of health services at the Health Center, said in an email that the doctor Wirth named denies the allegations, and that they were “inconsistent” with how she regularly treats her patients.

Wirth said she had already internalized a lot of shame, and blamed herself for what had happened to her. She says she remembers the doctor reinforcing that feeling.

“I felt like I was crying for help, and they weren’t really answering that cry,” she said.

“I felt like I was crying for help, and they weren’t really answering that cry.”

“In these kinds of crimes, when power and control is taken away from somebody, we have to do everything we can to give it back,” Woods said. “When a victim makes a decision about how to move forward, we have to do everything we can to support them.”

“All clinicians at the Health Center are trained and knowledgeable about how to respond to victims of sexual assault and offer appropriate resources to the student, including testing for STIs, sexual assault exams from a facility specifically trained and equipped to collect forensic evidence, and counseling on or off-campus,” Dr. Jones said in the email, which was sent through university communication officials.

“The Health Center supports students in making decisions that are best for them,” he said.

Wirth says she didn’t feel supported by the university at all, and left the health center that day with only two STD tests – for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea – and no longer had any intention to collect evidence or pursue any form of justice for what had happened to her. She chose not to go through an investigation.

Not long after her visit to the Health Center, Wirth, who is on scholarship at SMU, says she was shocked to find out she had been billed over $400 for the two tests she did receive. She had to pick up a part-time babysitting job that semester to pay it off.

“I didn’t tell my parents what had happened, and I was just 18 years old,” she said. “So I ended up trying to secretly pay it behind my parents back.”

The SMU senior has since come to regret her decision to not pursue an investigation. She believes that the health center official ultimately prevented her from collecting evidence that could have given her a fighting chance, but there is no way to know for sure if even that kind of evidence would have been sufficient.

Swept Under the Rug

After months of the exhaustive Title IX investigation, the student who did not want to be identified would find out that the evidence she had meticulously collected wasn’t enough to prompt any action from the university.

In the determination letter, through which the office informs students of an investigation’s finding, officials said security footage showed she was not drunk enough to constitute a loss of her ability to consent.

“You stated that you were incapacitated due to alcohol and unable to consent to sexual contact and sexual intercourse,” the letter reads. “A video reviewed by an IAE investigator of you…walking through the [residential hall] first floor lobby and entering the elevator showed no signs of you being incapacitated. Two witnesses stated that you showed signs of being under the influence of alcohol…but you were not incapacitated.”

SMU’s Title IX policy states that “someone who is incapacitated (by alcohol, drug use, unconsciousness, disability, or other forms of helplessness) cannot consent.”

While the policy does not address what level of alcohol intoxication constitutes incapacitation, it does note the following:

“For a respondent to be held responsible for a Policy violation due to incapacitation, the complainant must be unable to consent to sexual activity, and the accused must have reasonably known that the complainant was incapacitated,” Thomas said over email, in response to questions about the standard for incapacitation.

The student now says she almost regrets reporting the incident to SMU at all.

“It was one thing to have it happen,” she told The Daily Campus, struggling to hold back tears. “But honestly, I think what was worse than that event was the process of going through [the Title IX investigation], having to rehash it, only to have the university tell you that they don’t find any credibility in your story.”

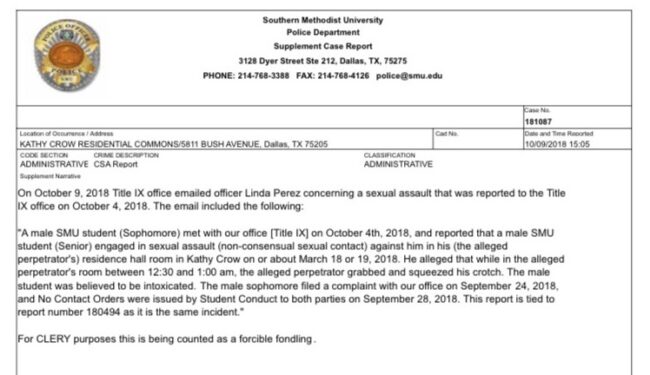

SMU senior Jack Davis feels the same way about how the university responded to his case. He reported an incident in which the president of his residential hall, who Davis claims had a reputation for predatory behavior, allegedly groped him in Kathy Crow Commons during his freshman year.

“I think that the trauma can even be worse, not even from the assault, but from how people handle things. And the way that SMU chose to just sweep me under the rug, and shun me and think that I was just going to be quiet and go away, that was almost worse than what happened to me,” he said.

The way that SMU chose to just sweep me under the rug, and shun me and think that I was just going to be quiet and go away, that was almost worse than what happened to me.

Davis says after he made his initial report, the Office of Institutional Access and Equity never followed up.

Months later, he says he followed up with the office himself, as he was training to step in as the new RA for the building during his sophomore year.

“They looked at me like I was crazy,” Davis said. He claims he was later informed the staffer in charge of his case had left the school over the summer, and that’s why his report was never handled. Davis then says he got the office to formally investigate the reported incident.

“IAE cannot comment on individual cases. However, if there is a delay in an investigation, the parties are notified and the delay does not affect the outcome of the case,” said Thomas, who in addition to being the Title IX coordinator, is also the director for access and equity and the executive assistant to President Turner.

On the same night Davis received RA training regarding mandatory reporting for sexual misconduct, he recalls a female student confiding in him that she was raped by a football player. Davis said he felt more conflicted than he should have been to report the incident to SMU, because he had experienced first-hand how ineffective the process was.

“It was kind of hypocritical,” Davis said of the sexual misconduct training. “We had to sit there and listen to them lecture us, and tell us how much they care about us, but when it actually came down to it, nobody did anything.”

Davis says he was told that a decision about his investigation would arrive no later than Oct. 31, 2018. On Nov. 2, two days after their deadline, Davis finally received a determination from the office.

“Based on our review and analysis of the information obtained during this investigation, IAE has determined that there is insufficient evidence…,” the letter read. Davis was shocked, because he claims he had a witness who was there when the incident happened.

“Somebody was in the room when it happened, and they consider that insufficient evidence,” he told The Daily Campus, chuckling to himself in frustration. “I was just so curious what they even looked at…like what did they even look into? It was never really explained to me.”

Living With The Consequences

Davis says that while working as an RA, he heard of more incidents regarding the student he had made the report against. That student continued to live in his residential building after the ‘insufficient evidence’ finding. Davis says he then decided to walk into the IAE office in person to have a conversation with the Title IX coordinator.

According to Davis, Thomas did not respond well to him walking into the office unannounced. Looking back, he believes the Title IX officials’ lack of responsiveness and general apathy are the office’s biggest issues.

“I was assaulted, my residents were getting assaulted, and we can’t even have a conversation,” he said. “But I can’t say I’m surprised to at the end of the day, because SMU does have an ugly track record of this.”

Woods, who works with local Title IX coordinators regularly, says that the Title IX process at universities may not be the most effective way to pursue criminal justice, but are at least intended as a pathway for students who experience sexual assault to receive housing or schedule accommodations.

However, SMU’s Office of Institutional Access and Equity may not even provide that much.

“The toughest thing for me was living in the same building [as my abuser],” Davis said. “RLSH (Residential Life and Student Housing) wouldn’t let me leave.”

He says he had requested to be moved to another residential building, but the university said they could not provide him with another housing accommodation that met the needs of his medical disability. Instead, Davis says he fought with RLSH to let him leave campus, but they repeatedly denied him a housing exemption. He eventually chose to move off-campus on his own, without permission from the university.

“That is clearly an injustice, simply for the reason that Title IX definitely covers that they are entitled to that,” said Woods. He believes that sometimes the issue is the lack of resources available to Title IX officials that can make it difficult for them to properly address their cases.

“During the investigation process, if both parties live in the same residence hall, all complainants and respondents are informed that they have the option to request to move to a different residential building,” said the Title IX coordinator over email. “In addition, complainants are informed that they may request a No Contact Order, prohibiting the parties from making contact with each other.”

When Davis read about the case detailed in the lawsuit, he was upset to learn that another student had experienced the same kind of housing situation he had.

“I’m not surprised. And that really disappoints me,” he said in September. “I’ve said this in the past, you know, I’m probably not the first and I’m definitely not the last, and here you go.”

Students interviewed by The Daily Campus who did not pursue an investigation from the office, but instead requested campus accommodations, say that officials were often frustratingly unresponsive to their communications and unavailable to help facilitate academic arrangements.

Holding SMU Accountable

As a student senator, Davis formally proposed the formation of a student committee last year to review SMU’s Title IX policies. He now leads the committee with six other students who have been meeting regularly to propose changes to housing policies, health center services, and the reporting process.

Davis says the experience took a toll on his mental health and his education, and he hopes to prevent other students from going through the same thing. “You can’t expect somebody to live in that kind of environment,” he said. “I almost dropped out of SMU.”

In early October, SMU President R. Gerald Turner sent out a routine campus-wide email encouraging the SMU community to report sexual misconduct on campus.

“SMU is committed to maintaining a supportive environment for affected members of our campus community to come forward immediately to obtain help and report incidents,” the message said. “Our University continues to work on multiple fronts to eliminate sexual misconduct, provide care and support to those who experience it, and hold violators accountable while treating all parties in a fair manner.”

Jack Davis says transparency from the university regarding campus sexual assault, and how cases are handled, would help the campus community better address the problem. But SMU claims to keep most of this information confidential in the interest of student privacy.

According to Woods, it’s to be expected that universities would work to preserve their federal funding and minimize their public reputation for campus sexual assault.

“They are trying to protect the institution as best they can, while trying to serve the students as well,” he said, highlighting a potential conflict in the internal reporting process at universities.

“So far I haven’t seen anything that gives me good faith that they are taking steps to fix this,” the unnamed student said at the end of her interview. “The language is very pretty, they talk a lot about support. But if you don’t see that in practice you don’t really believe it.”

The language is very pretty, they talk a lot about support. But if you don’t see that in practice you don’t really believe it.