Everyone takes a bad photo now and then. You blinked, there was a weird fold in your clothes, your smile looked strange, Venus was in retrograde, whatever happened, it wasn’t your day.

However, for people with darker skin tones, while your eyes are sparkling and your whites are perfectly pearly in person, on Instagram you look… different.

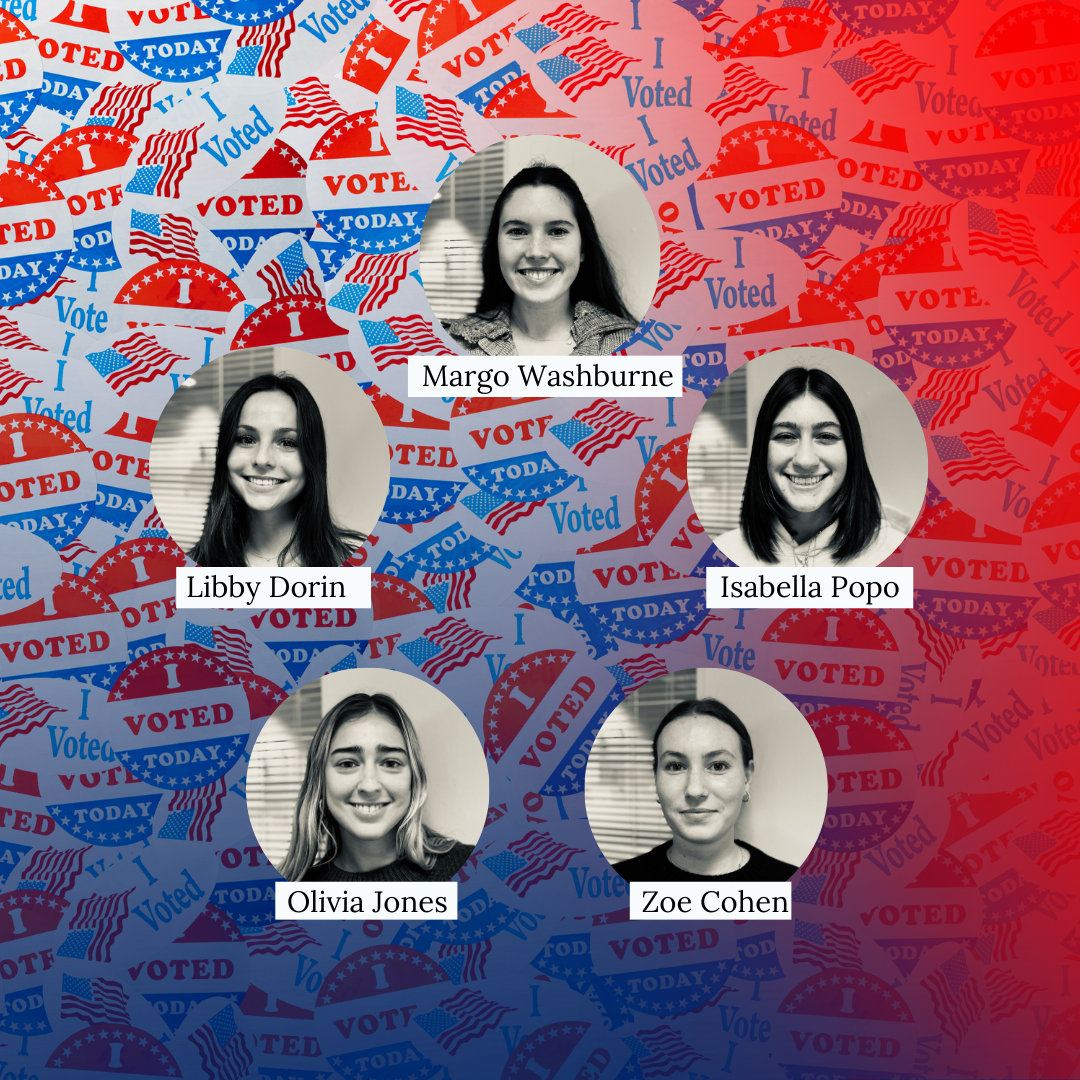

Group shots with people who have a lot of variation in skin tone are often the worst offenders. Jerry Crayton, a Black SMU alum, and a professional photographer at Sunwest Communications in Dallas, has plenty of experience with this.

“I was in a group photo on campus one summer, and when I saw it posted I was like, oh God, you can’t even make my face out,” Crayton, who graduated in 2020, said.

The photo Crayton referred to was taken in the George W. Bush Presidential Library. The huge windows provide a very unflattering backlight, and the filter applied to the photo, though it left his white counterparts largely unaffected, cast Crayton’s entire face in shadow.

The experience of having your skin tone poorly represented in photos transcends iPhone photography and can follow people with dark skin into the professional world as well. SMU senior Kaitlin Slaughter worked and modeled for a boutique on Lovers Lane, only to find that the quality of her photos differed vastly from those of her white coworkers.

“The photos were edited so poorly that I was a completely different skin color,” Slaughter said. “I looked awful. I could tell that the editor had made a filter for the white girls, and she put it on me, and it looked like there was a shadow over my entire body.”

This unfortunate reality dates back to the inception of color film, which in effect was made for white people. Color film was an exciting and groundbreaking technology. The film is coated in layers of chemicals sensitive to different colors of light. After a photo is taken, several different chemicals are used to develop the film. These chemicals in combination with each other are what determines the color balance of a photo.

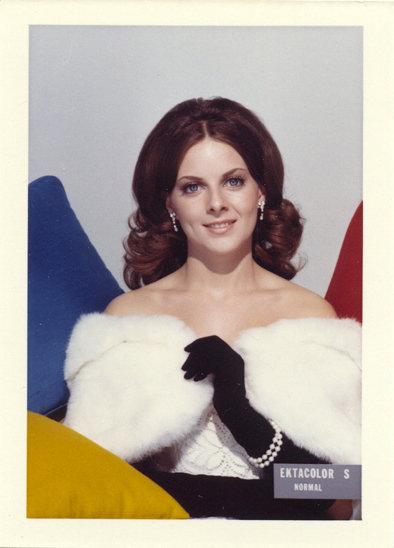

However, the technology was developed specifically for white skin tones. The photo used to calibrate the color balance, called a “Shirley card”, was a dark-haired white woman in a fur coat. As a result, people with darker skin tones were often left looking sickly and grey or rendered a featureless shadow in photos.

This wasn’t an issue for the film company Kodak until it began to receive complains from manufacturers of wood and chocolate who were upset that their products were being misrepresented. To ensure there was justice for mahogany chairs and milk chocolate, Kodak developed a new type of film, Kodak Gold Max, which they boasted was “able to photograph the details of a dark horse in lowlight.” The company also offered more Shirley cards, representing a more diverse range of skin tones. This change did not occur until the ‘90s.

“The idea of the Shirley card, and of Kodak specifically building racial bias into the film formula was not even being discussed when I was an undergrad in the year 2000,” Lisa McCarty, assistant professor of photography at SMU said.

Even after changes were made to the technology, it wasn’t until very recently that the issues of implicit bias in technological innovation were brought to the forefront of the public eye. Much of the attention that has been drawn to the issue has been due to advocacy by Black photographers.

“It took the Teju Cole piece and the Sarah Lewis piece to really open up the discussion publicly,” McCarty said, referring to two New York times pieces authored by Black photographers focusing on racial bias in photography.

Most people aren’t using film cameras to take their Snapchat or Instagram photos – they are using their smart phones. Despite the advances in technology and the photo filters that many platforms offer, people with darker skin are facing many of the same issues for many of the same reasons.

Snapchat is infamous for filters that handle dark skin very poorly. Assuming the filter recognizes your features as a face, your skin and irises are usually lightened, your nose shrinks, your eyes grow: you’re anglicized in real-time. Instagram’s filters are slightly better in that they do not fully reconstruct a person’s face. They do, however, fully reconstruct undertones, leaving people with dark skin with various shades of mottled blue, grey, and green in photos.

Looking undead in a group photo does pale in comparison to issues like systemic oppression or structural violence. But, ultimately, it is still a reminder that the world we live in is calibrated for white people, and that if you have darker skin, you will be forced to navigate that in what feels like every aspect of your waking life.

“It’s embarrassing,” Crayton said. “Just thinking about how I’m probably the butt of some joke because of that photo. I wanted them to take it down to be honest.”

In a world where your image is so intricately tied to both social capital and self-worth, the lack of care for darker skin seems very pointed.

“It’s painful,” Slaughter said. “It’s like another slap in the face. It makes you feel like no one cares about you.”

The best way to fight this is to be cognizant of the issue. Look at the dark-skinned people in your photos before you post them and ask yourself: “Is that what they look like in real life? Is that what their skin looked like when we took this photo? Is this what they look like on their social media pages?” People with dark skin do not want to look sickly. They do not want to look grey. They want to look like themselves.

Take your photos in good light, preferably sunlight. Fluorescents aren’t good for anyone, but they give dark skin a particularly off putting cast. If there isn’t enough light, flash is not the balm many treat it as. The distance between the camera and the subject is too great for the flash to do anything but cast unflattering shadows. When putting filters on people with brown skin, tend towards warmer ones that bring out the reds, yellows, and oranges in our skin. Be careful of filters that are high contrast, as they make the light parts of the image brighter and the dark parts of the image darker, which can cast entire parts of our faces in shadow.