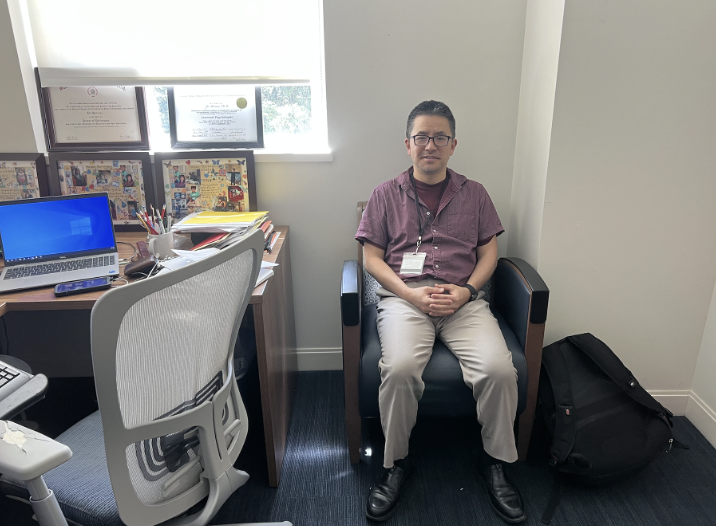

Houston gives a tour of SMU (Photo by Essete Workneh)

It’s a Tuesday afternoon and Matt Houston is scratching one more thing off his to-do list. He is giving a tour of Southern Methodist University (SMU), his alma mater, to leadership students from Texas A&M Commerce. The students are visiting SMU to attend the Tate Lecture Series; as they wait for the tour to commence they huddle around their designated guide, attempting to escape the February chill.

A Man on a Mission

“If you have any questions say, ‘Hey guy in this fly jacket, guy in the sweater, or hey Matt,’ which I prefer,” Houston announces to the small crowd. Houston is dressed in a navy blazer, light khaki slacks, and a white button-down shirt he wears under a red sweater. His brown-rimmed glasses perfectly match his brown belt and brown suede dress shoes. For Houston, success is in the small details. The importance of appearance is a lesson he learned from his older sister, and something Houston credits with changing his life. “That helped me out whenever I met people. First impressions are lasting impressions,” he says matter-of-factly in our first interview. “My image is very important to me, because I represent more than just me when I walk.”

In between monotonous tour references Houston weaves in remarks about rapper Trinidad James-“He’s actually smart, did y’all know he was an entrepreneur? He’s still ratchet though”-and describes the SMU squirrels as “the most gangsta squirrels in the South West region.” During the tour’s 10-minute break Houston gingerly slumps down in a chair, “I’m tired,” he groggily says as he rubs the sleep from his eyes. He just arrived in Dallas after a trip to Austin for the 2013 African American Legislative Summit, and only had time to change clothes before starting the tour. While the 29- year- old Houston’s main job is his role as the executive director of external affairs for Group Excellence, a tutoring and mentoring organization that coordinates programs with schools and community groups, his responsibilities do not end there. Houston is also the chair of the Dallas Black Chamber of Commerce and a member of the Urban League of Greater Dallas Young Professionals (he was president before his term lapsed in December of 2012). In February, Houston was named a 2013 Honoree at the Dallas Business Journal Minority Business Leader Awards.

His Inspiration

Houston started his first business at the age of 13. His father decided he was too old for an allowance and wanted to teach him the value of a dollar. He told Houston he would supply him with a lawn mower and gasoline, but the rest was up to him. Raised by a family of entrepreneurs, Houston took on the challenge with aplomb. While his mother was a teacher, his father received his MBA from New York University and was an investment banker in the 70s before starting his own pallet company. When Houston was born he was considered a blessing to his 40 year-old mother and 43 year-old father. His sister and brother were 10 and 15 years older, respectively, and Houston was always known as the baby of the family. By the time Matt was growing up in the early 90s, his father was at the top of his profession. No longer burdened with the worries of establishing a career, he was able to spend quality time with his son and offer him steady guidance. “The timing was so different, I think that my parents did raise him differently because he had a lot of individual time with them starting at a young age,” said Houston’s sister, Natalie Hunter.

Growing Up

Houston was raised in an Oak Cliff residential neighborhood and knew almost all his neighbors. His mom was a member of the PTA and was heavily involved in his school. As a child he played on sports teams with the other kids in his neighborhood; most people didn’t move around and he was raised with a strong sense of community. “It was the best experience of my life,” Houston said. “It built a sense of giving back, a sense of belonging, a sense of family outside your immediate family. People like that just developed me, it wasn’t a textbook, it wasn’t lessons that I learned from my parents, it was just interacting informally that showed me the importance of people,” he said.

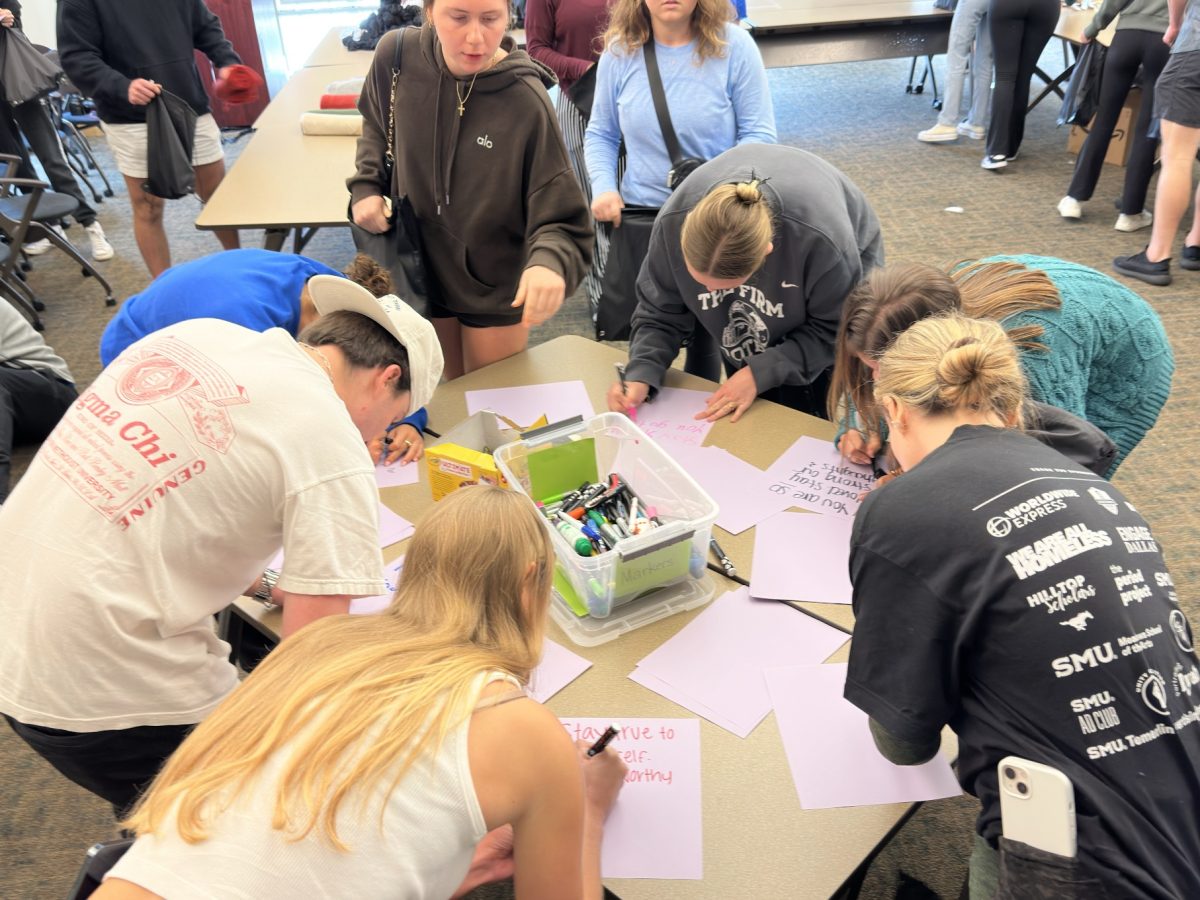

Joining the high school band allowed Houston to discover his passion for leadership. Having been a trumpet player since he was 10 years old, Houston was more of an introvert who was recharged by music and thinking. His role as a band sectional leader for Town View Magnet Center high school made him feel more comfortable in his skin. “I learned the good and the bad of how you motivate people,” he said. When Houston first started as leader he would require members to complete 100 push-ups for dropping a mouthpiece. When those methods sometimes backfired, Houston took a slightly different approach. “I would still make them do laps and push ups, but I’d do them with them,” he said. Houston’s enthusiasm for music has not waned over time. He currently plays New Orleans style music in a band called the Inner City All Stars. The group, comprised mostly of professional musicians, performs four to five times a month and has played at venues like the Dallas City Performance Hall.

After Houston graduated from SMU in 2006 his college friend Carl Dorvil convinced him to take a job with Group Excellence. Dorvil, who founded the tutoring company out of his dorm room in 2004, wanted Houston’s help with expansion efforts. While his parents were skeptical, Houston turned down a job with an investment company and quickly took on the challenge. He was part of the company’s initial expansion success and was excited about the achievement. He began to live the good life of a young, successful, college graduate in Downtown Dallas. In June of 2007, Houston had a rude awakening when his father, whom he considered to be his best friend, died of type 2 diabetes. His father had lived with the disease for 25 years, and his failing heath was one of the reasons Houston chose to go to SMU instead of considering acceptance letters from Morehouse and Stanford. Although the loss was tragic, the family had expected it. But that September they received a bigger shock when Houston’s older brother, Thomas, died of the same disease. He was cleaning his house pool when he fainted and was rushed to the hospital. Thomas had been informed of his diagnosis just a week before his death. Houston was devastated and his priorities began to change. His family losses, coupled with a failed fundraising effort for a friend’s non-profit foundation, gave Houston a major taste of humble pie. “At that time I thought that I was this brand, I thought that I was it and I realized that I’m nothing, so I need to be a servant,” he said.

Houston now relies heavily on the advice of mentors like Michael Rideau, a Senior Vice President of American National Bank of Texas, for guidance. “He was always supportive of his family, but he’s just taken on a more grown up’s role looking after his mom. Certainly when you have something like that it makes your family grow closer,” Rideau said. Houston himself has been a mentor with Big Brothers Big Sisters for a year and a half. During our interview he receives a text from his 15-year-old mentee. “He wanted me to take him to the movies so he could see his girlfriend. Hate teenagers,” Houston said with a chuckle.

The Road Ahead

For now, Houston is placing his focus on his greatest passion, education. “That’s the only way you can change people is to teach them” he said. While Group Excellence has been a for-profit since its founding, it is slowly transitioning into a non-profit, a status that will enable the organization to write more grants. The company makes much of its revenue through contracts with school districts and also has a federally funded program through the No Child Left Behind Act. As of now, Group Excellence is a 500-person operation that has grown to serve more than 50,000 students throughout Texas. Houston’s friend Ariann Cockrell worked as a Group Excellence area director; one day Houston dropped by a tutoring session she was conducting. “He was probably there like 15 or 20 minutes, but every day after that the students would ask, ‘When is he coming back?'” He really did leave a lasting impression on those students that day,” she said.

Still, Houston does not see his situation with Group Excellence as permanent. He has much loftier ambitions. “My plan is to be the most influential American, period,” he says without a hint of sarcasm. “When you have that as your goal, you’re not really satisfied, you can’t really lay back and say, ‘Oh yeah I’m doing great with this Group Excellence thing.” While he acknowledges Group Excellence has been a great stepping-stone, contentment is still out of his reach. “You know your fulfillment when you’re just happy; you’re being purposeful, it’s allowing you to support your family and you’re able to help other people. When you’re doing those three things, that’s when you can sit back and say, now I’m cookin’.'”