(Spencer J Eggers/The Daily Campus)

Nestled within the affluent neighborhood of University Park sits Highland Park High School, an institution whose navy and gold tartan is recognized across the country as a flagship of public school excellence. Located just five miles away is Woodrow Wilson High School, rated Academically Unacceptable by the Texas Education Agency (TEA) in November 2011.

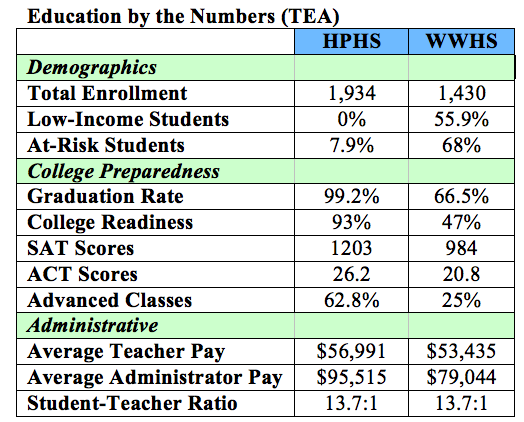

A 2010 to 2011 campus profile by the TEA found that the difference in funds spent per student at the two schools is slight. However, Woodrow Wilson’s population consists of 68 percent at-risk students, compared to Highland Park’s 7.9 percent. In addition, fewer students at Woodrow Wilson pass the state’s standardized TAKS tests.

The discrepancy between levels of public education throughout the Dallas metropolitan area is a widely acknowledged problem — and one that public officials and school districts have continually failed to address.

Economic differences throughout Dallas school districts impact the caliber of education students receive.

Highland Park High School

Newsweek ranked Highland Park High School 31st on their list of “America’s Best High Schools” for 2011.

Highland Park physics teacher Jeff Barrows attributes the students’ success to the school’s familial community.

Highland Park students “aren’t the first in their families. There is a precedent that precedes them in terms of academic stature,” Barrows said. “They’re nurtured that way at home. They are inquisitive because they have been asked to be that way outside of the classroom.”

Thomas Walter, a senior at Highland Park High School, serves as student manager for the school basketball team, is a member of multiple academic clubs and assists teachers in tutoring his fellow students. He agrees that parental involvement is key. Walter said his father, who was once in the Navy and his mother, a former high school English teacher, both contributed greatly to his success.

“I was never really pressured to succeed; I was set up in an environment that self-motivated me to do well,” he said.

Helen Williams, the communications director at Highland Park ISD, emphasized the importance of having a family that encourages education and makes it a top priority.

“You can’t overstate the importance of a mom and dad that value education,” Williams said.

Parental involvement impacts even the most minimal parts of Highland Park’s system. Instead of a school-employed cafeteria staff, parents serve the food. This program has been a long-standing tradition and allows the high school to spend more money on other educational endeavors.

Private funding programs, such as the Highland Park Education Foundation, offer additional finances to those provided by the state and also help mitigate the fall-out from funding shortages. In affluent areas, like Highland Park, the money generated from these programs frequently exceeds the raising capability of many other Dallas school districts.

Dr. David Chard, dean of SMU’s Annette Caldwell Simmons School of Education and Human Development, said the money the education foundation produces plays a considerable role in the high school’s performance.

“This organization raises a tremendous amount of money to support teachers’ education (paying tuition), extra-curricular activities, etc.,” he said. “These things likely impact the effectiveness of teachers as well as students’ motivation to stay in school and work hard in school.”

According to the Highland Park’s school profile, more than half of the students participate on athletic teams and approximately 80 percent of Highland Park students are involved in extracurricular activities. Academic achievement is also made a top priority; in the 2010 to 2011 school year, 69 percent of students who took an advanced placement exam scored a three or higher.

Barrows attributed much of the achievements on the students’ individual drive to succeed.

“There is no brand that is unique to Highland Park. Honors kiddos are honors kiddos,” he said. “They are highly motivated and have a curiosity that says why and a desire to understand it so that they can personalize their knowledge.”

However, Barrows regards the time he spent teaching in an environment where the students were not as motivated as “humbling” and “the hardest thing” he has ever done.

“Addressing the needs of the students who aren’t going to define themselves academically in high school is a bigger challenge,” he said.

For schools that lack adequate funding and parental involvement, motivating students is a more difficult challenge. Teachers are often times forced to jump these complex hurdles without the resources provided to wealthier districts.

Woodrow Wilson High School

Woodrow Wilson High School opened its doors 83 years ago. It is currently one of the largest special education programs in the Dallas Independent School District, with an award-winning performing arts department, mock trial team and athletic program.

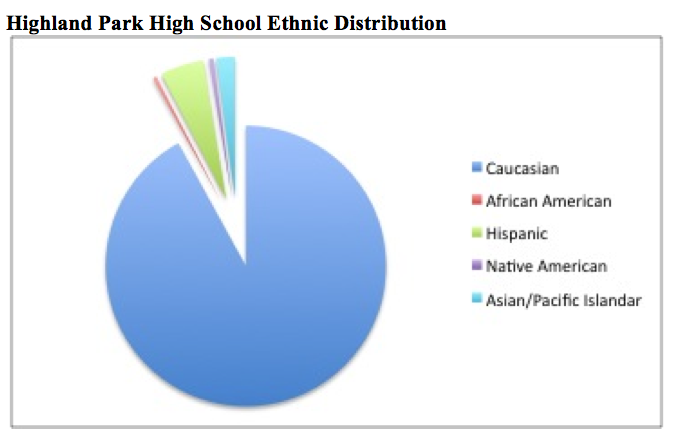

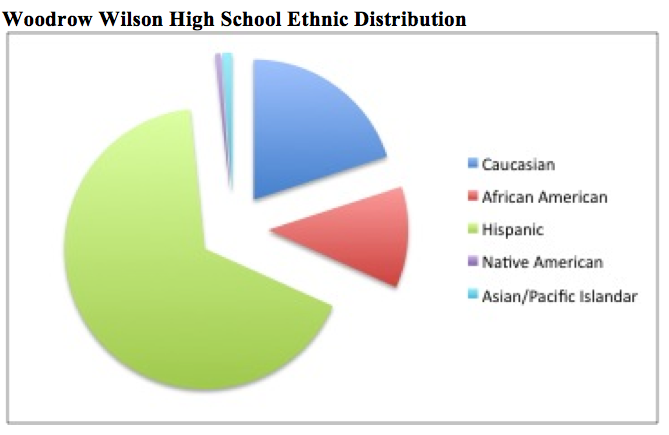

Woodrow Wilson’s student population consists of 80 percent minorities.

According to Dr. Kathy Scherler, the International Baccalaureate (IB) coordinator at Woodrow Wilson, the school’s rich diversity gives students “an experience in what life will be like in the real world.”

Woodrow Wilson is one of four Texas candidate schools for the IB Diploma Programme, according to The Dallas Morning News.

Sophomore IB student Robert Bolt said his parents encouraged him to join the IB program at Woodrow Wilson.

“The teachers are great; they’ll help you with anything. If you want to learn, you’ll learn. If you want help, you have to go ask the teacher,” Bolt said about the program.

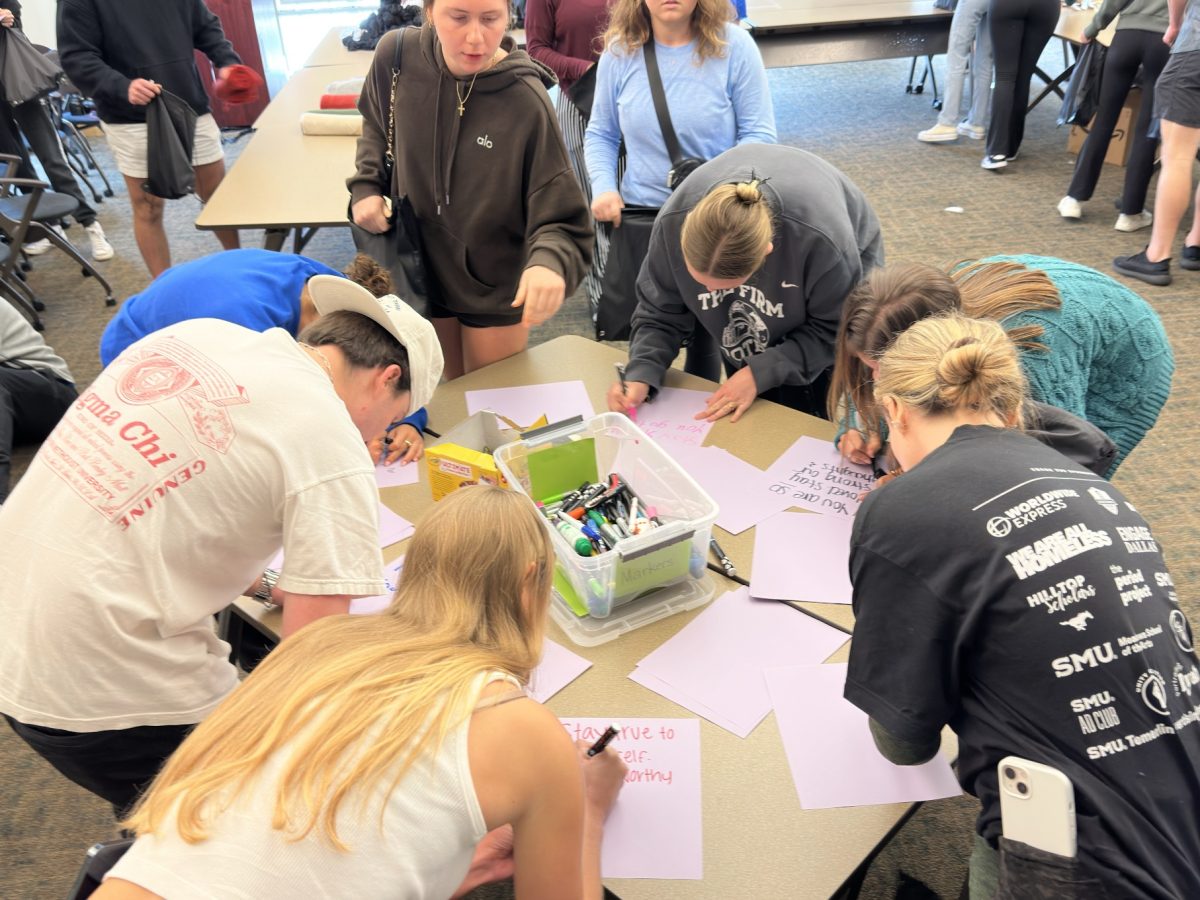

In 2009, the Woodrow Wilson High School Community Foundation was created in efforts to raise funds, grants, scholarships and other programs and projects.

An IB Diploma costs $750 for registration and exams, which many of the school’s students cannot to afford.

The Community Foundation announced in November that the school’s IB program was the first to receive grants from the Ann Jacobus Folz Fund for IB Financial Assistance, which will help cover the high cost of registration and examination fees for 15 students.

The school consistently faces financial hurdles. Recent budget cuts caused the school to reduce their custodial staff to two and to discontinue their Professional Learning Community.

In a recent advisory board meeting, Scherler discussed ideas to meet 10 of the school’s greatest needs which include: technology, elective equipment, green movement, staffing needs, textbooks, staff development, graduation site, partnerships, cafeteria and leadership.

While Woodrow Wilson heavily depends on their PTO and alumni for financial support, the parental involvement is limited due to the fact that a majority of the students’ parents are employed.

Education as a Human Right

Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights considers education a human right and U.S. federal and state laws mandate education, factors of poverty, class and access to an education determine the quality of education people receive.

Dr. Rick Halperin, the director of the SMU Embrey Human Rights Department, blames the discrepancy between schools like Woodrow Wilson and Highland Park on the lack of focus given to economic injustices.

“When economic issues are linked to education, then it’s clear that not all students get the same educa

tion,” Halperin said.

Of Woodrow Wilson’s student population, 55.9 percent come from low-income households. In comparison, a low-income population does not exist at Highland Park.

While both Woodrow Wilson and Highland Park are comprehensive high schools that exceed expectations of the average Texas high school, statistics show a drastic difference in college readiness.

The Dallas Morning News reported 93 percent of Highland Park’s students as college-ready compared to only 47 percent at Woodrow Wilson.

Both schools exceed expectations based on their individual circumstances; the two schools cannot be compared to each other on an equal scale because they have an unequal set of challenges.

“It’s simple. Do we care or do we not?” Halperin said. “Apparently, we don’t, or we don’t care enough.”