Crisis management

An article in Tuesday’s edition of the Wall Street Journal noted the conspicuous absence of corporate communications courses in MBA programs and business schools in general. Specifically, the Wall Street Journal piece cited crisis communication and reputation management as two areas typically not included in the standard MBA curriculum.

The article’s author, Ronald Alsop, points out that business schools tend to offer courses in crisis communication when the subject is timely, i.e., after a major corporate crisis. The fact is, in today’s business environment, there’s a “major” crisis almost every day, hence the need for a college-level crisis class every semester.

Don’t believe a crisis management course is necessary? Just ask our friends down at Baylor and Texas A&M or the folks at the NYSE, Texaco, Snapple, Six Flags, Duke Medical Center, Worldcom, Tyco, Denny’s, HealthSouth, NASA, the Olympic Committee, the Catholic Church, the New York Times, or Firestone. Rush Limbaugh, Pete Rose, Martha Stewart, and Kobe Bryant might have an opinion, as well. According to one study, 70 percent of all major corporations have experienced a crisis, and the percentage is increasing.

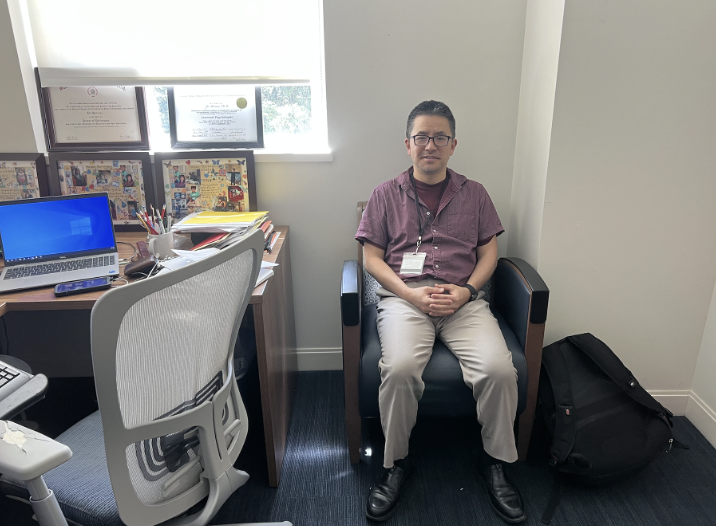

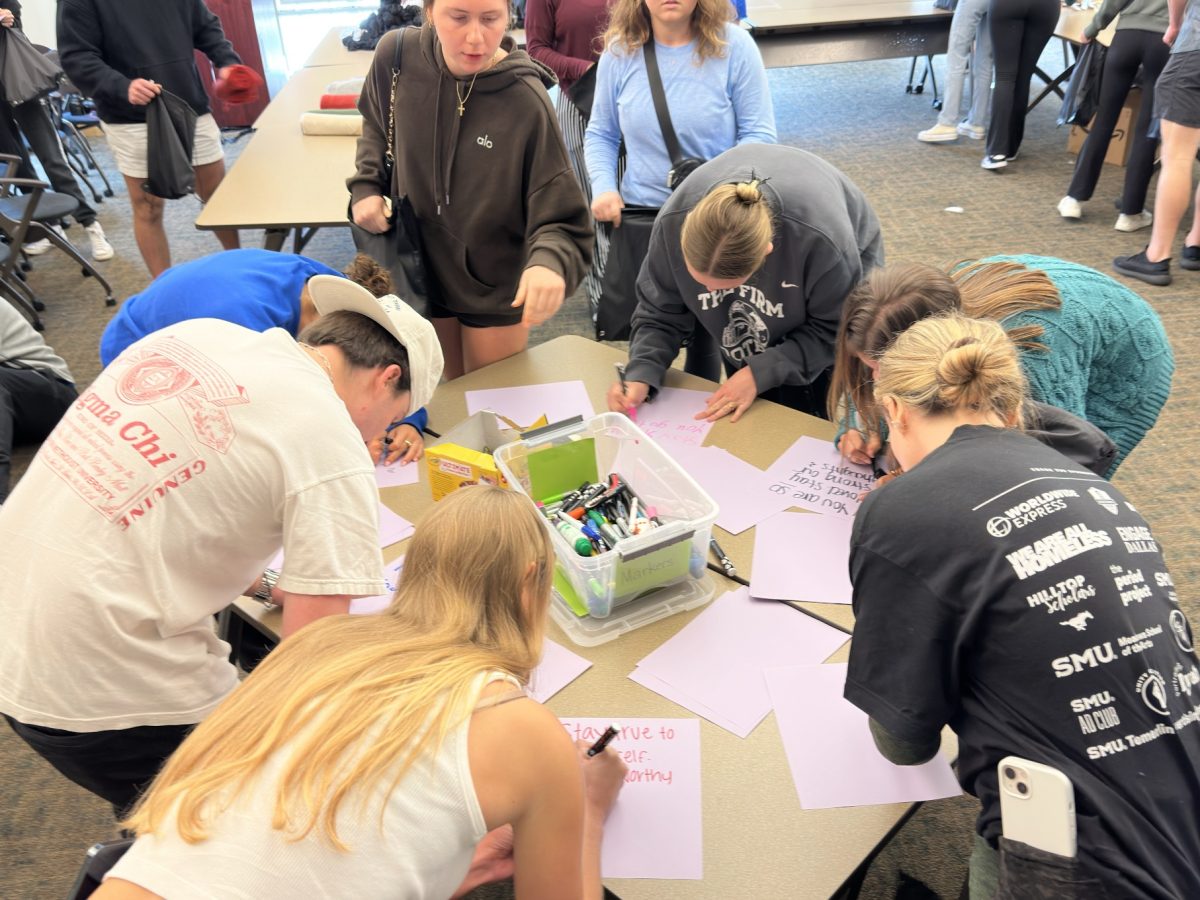

What’s interesting is that SMU’s Division of Corporate Communications & Public Affairs (CCPA) has, for more than five years, offered a course in crisis management, usually in both the fall and spring terms. Designed to provide students with strategies and tactics for systematically preventing or modifying the impact of negative events on the organizations they work for, the crisis management course consistently ranks as one of the Division’s most popular courses.

Crisis management is closely linked with credibility, trust, and reputation, which is driven by a person’s or an organization’s actions and experiences over many years.

As a result of the growing number of institutional scandals, unreasonable corporate salaries, and outright lies of our most respected institutional leaders, Americans claim they don’t know who to trust anymore.

The same surveys show that Americans tend to trust organizations that assume responsibility and accountability, visibly show concern for customers and employees, are actively involved in the community, communicate openly with stakeholders, and are transparent and direct in times of crises. Strategic communications professionals, well-versed in reputation management, have been advising their CEOs and clients to do these things for years. As our students learn, trust and credibility exist because of performance and action, not “spin” or “hype.”

As noted in the Wall Street Journal article, the problem with concepts such as reputation and trust is that they’re intangible. But, as noted in a 1999 article in The Economist, “The value of a business increasingly lurks not in physical and financial assets that are on the balance sheet, but in intangibles.” By intangibles, the magazine is talking about key assets such as brands, employee loyalty, public trust, corporate credibility, goodwill, social responsibility, relationships, and organizational reputation. Unlike other assets like inventory, these are difficult to measure, thus judged to be less important.

But CEOs see the value. According to one survey, 96 percent believe reputation is important to their companies. Nearly 80 percent believe a good reputation helps sell products and services. And 60 percent believe a good reputation helps attract good employees. In the words of Warren Buffett, “If you lose dollars for the firm by making poor decisions, I’ll be understanding. But if you damage the firm’s reputation, I will be ruthless.”

Over the last 10 years, business leaders have realized that reputation is a legitimate strategic concern. Fortune magazine’s annual reputation issue is an example of this realization. Studies have found that the companies on Fortune’s “Most Admired” list invest more in the strategic communication function than other companies. There is greater support for it internally; they devote more resources – both financial and human – to it; and they provide more direct access to their executive officers. That’s because strategic communication can influence the intangibles like no other department in the company. In fact, intangibles – reputation, perceptions, credibility – is what our business is all about.

The emerging role of strategic communication is also evident at highest levels of American government. Many of the most trusted advisors to recent U.S. Presidents have hailed from the communication field. SMU alum Karen Hughes, still considered to be one of President Bush’s most trusted advisors, has enjoyed a long career in political communications strategy. Karl Rove ran his own public affairs for 20 years before joining the President’s staff. Mike McCurry, David Gergen, George Stephanopoulos, Michael Deaver, and Victoria Clarke – all communications strategists – have played significant roles in the White House over the last two decades.

Corporate recruiters consistently rate communication as the most important attribute for MBAs. Today, most chief executives spend the majority of their day working on communications issues. They’re communicating with employees, investors (and potential investors), analysts, members of the news media, customers, and business partners. For the most senior members of an organization’s management team, it’s less about business theory and more about communication and persuasion theory.

It seems that, to most business schools, corporate communication means lessons in memo-writing and instruction in public speaking. No wonder business students have negative perceptions of the field. Crafting business letters and getting tips on voice projection is pretty tactical stuff. Unfortunately, it has little to do with what’s actually being taught in SMU’s communication division.

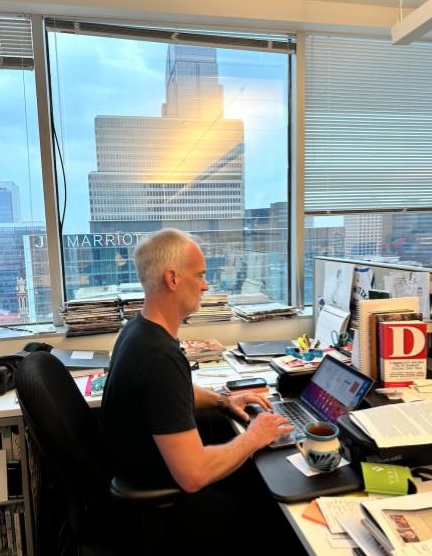

I’m a graduate of SMU. I’ve worked for nearly 20 years for a number of organizations, big and small. For as long as I remember, communications professors and practitioners have urged their students and interns to take as many business courses as they can. It seems that business students, many of whom have their sights on someday running a company, might well be wise to begin taking a serious look at what’s going on in the communications field.