Once every three weeks, seven individuals aged 20 to 40 meet for an hour of music. Through improvisation, interaction, singing and drum playing, they learn ways to overcome barriers posed by their mental and physical disabilities.

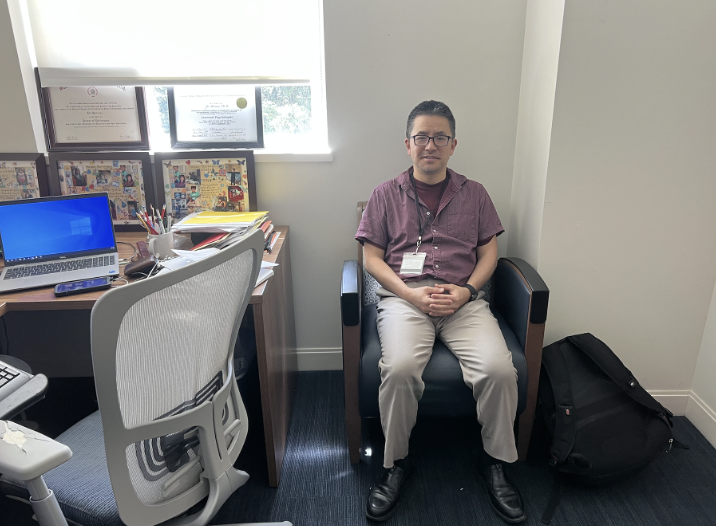

Their session is part of a four-year music therapy program headed by Dr. Robert Krout and offered at Southern Methodist University. The program’s small size is one of its main characteristics. Four students are currently enrolled in the program and work as therapists as part of their practical experience.

Clients, who attend sessions at no cost, get a beneficial input. Each individual, Krout said, will come to a session with a specific set of goals depending on the disability. But the general objective is to develop specific skills, such as communication, and provide mental order and direction in individuals who are unable to represent themselves verbally.

Progress in the clients’ communication level is measured through a series of risks in which they are asked to experiment new actions until they become part of their environment.

Zach Laviola, a two-year old autistic child, attends weekly music therapy sessions at SMU. His therapist, Robyn Kress is a senior student. Both Krout and Kress expressed positive remarks on Zach’s progress during the therapy—a progress made possible by Zach’s ability to remember and imitate sounds played through instruments.

Living within a music environment gives Zach an orientation. Krout explained: “Progressively there are times when you’ll see him in the music therapy where you wouldn’t say, ‘Oh, that’s a child with autism’ You would say, ‘That is a child interacting creatively in music.’ And the disability is not the most evident. Music can be a real equalizer.”

Kress considers Zach a “special” child for his playful interaction with music. Zach possesses the advantage of growing in a musical environment where his older siblings sing and play the piano. “He’s just naturally musical,” Kress said.

In a Channel 11 report, Mara, Zach’s mother, recognized some changes in Zach’s interaction with his surroundings. She explained: “He [Zach] has changed from a child who didn’t seem to have any interest in the world to a child that’s joyful, happy and giggling. When he hears music, he just comes alive.”

In the therapy program, Krout works with cases of autism, Down syndrome, mental retardation and developmental disabilities. In all cases, he conducts individual and group sessions, depending on the need of the clients.

According to the American Music Therapy Association, people diagnosed with autism respond well to music therapy because they show a high interest in the discipline. Kress added, “Autistic people respond to music because they’re unable to differentiate their environment. They perceive their environment as complete chaos and music is a unique way to add structure to their environment without forcing it to them.”

But sometimes, Kress said, autistic people don’t respond to music therapy because they are not interested or don’t have prior experience with music they can relate with.

The orientation and mental order individuals acquire is meant to endure in the future. Orientation, Krout said, can be reached by using a variety of skills during a session. Cognitive skills and improvisation are used within a creative process to give the clients the opportunity to socialize and listen to each other.

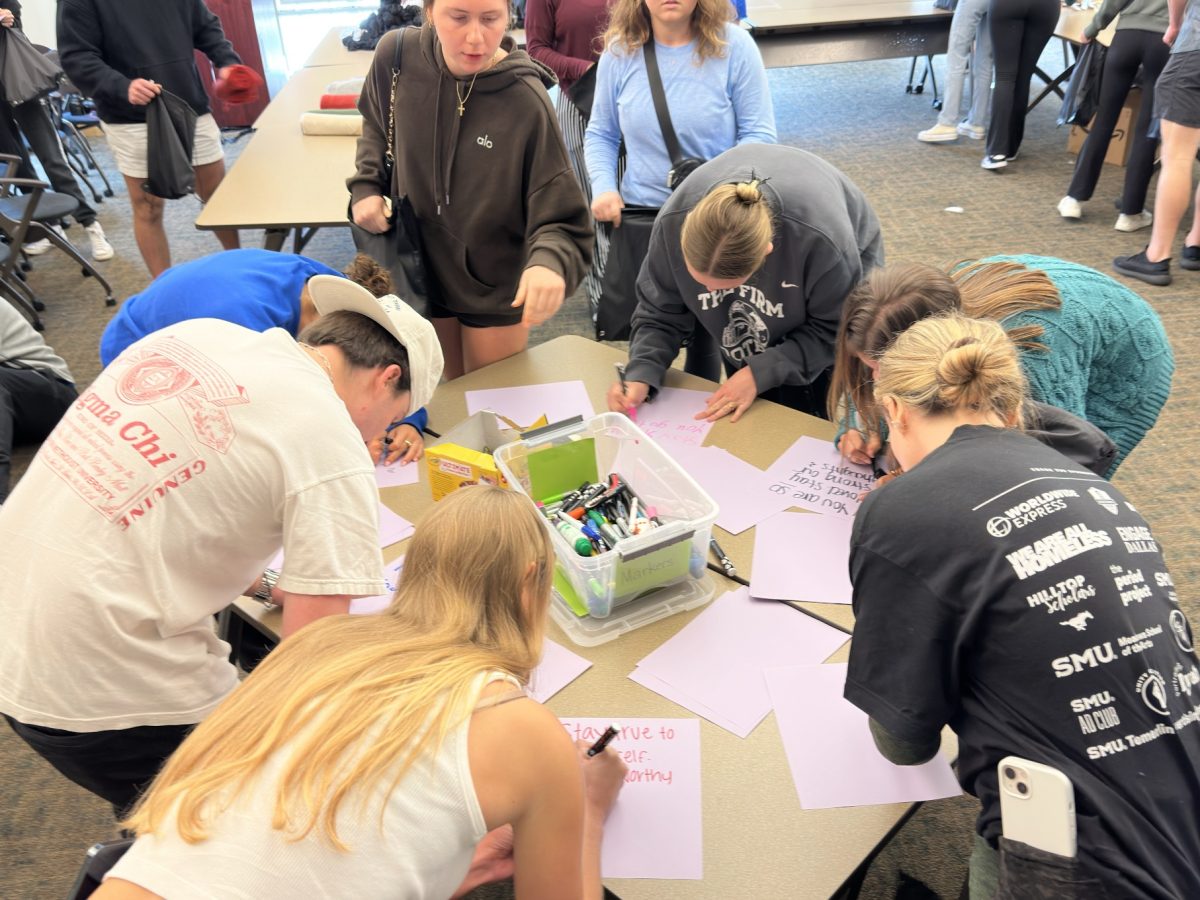

Individuals with developmental disabilities practice cognitive skills through singing, talking and playing the drum. Krout holds a group session with seven clients having different impairments, from Down syndrome to developmental disabilities. The session starts with the “Hello Song” in which clients take their turn to tell what they did since the last session.

Through this activity, their interaction and joyfulness comes up. For confidentiality reasons, the clients’ names have been made up. Michael looks excited; even though he’s been busy with work, he happily announces he’s going to England. “Across the ocean,” Michael emphasizes to the class.

A flow of energy runs through the bodies and minds of these individuals. Through music, their disabilities become hidden and they become more prone to success. Krout said, “We use music experiences that are accessible to the skill level of the client and then we use the creative process at the level they’re at as a way to communicate.”

In this group session, the clients are Beatles and Beach Boys’ fans. To enhance their level of participation, Krout makes them choose a song from both bands. While he plays the guitar, they follow, singing, clapping hands, snapping fingers and tapping the floor with their feet in a synchronized movement. Krout asks them to switch pattern of movement, allowing each one to take risks in the process.

Everyone tries to follow the group while Krout invites each individual to reciprocal listening. At one point, Krout plays “Sloop John B” by the Beach Boys on his guitar, and Michael helps him follow the songs’ notes by turning the book’s pages. Everybody sings the refrain following a different vocal style, a different body movement, a unique facial expression and yet recognizing the familiarity with the song.

Michael takes the risk of a new action, turning pages, sometimes turning back or slow or fast. At the end of the song, he seems tired as if turning pages exhausted him. Before playing “Eight Days A Week,” the next Beatles’ song, Michael said, “It’s really hard to turn pages. Can we do something without turning pages?”

Krout recognizes the struggle and shares his view in an empathetic way. “It’s hard work being a page turner.”

Even though it may not be evident, improvisation is led by the clients. Each individual is not forced to follow a specific music pattern; Krout adapts the session’s activities to the client’s mental and physical disabilities and keeps the interactive process flexible and dynamic.

However, difficulties may arise depending on the client’s case. Currently, Krout’s tough task is working with an eight-year old boy affected by autism.

Interaction with musical instruments didn’t provoke any reaction at the beginning, until he learned about the boy’s fascination with toys that turn on and off. One day, Krout brought a guitar toy to the session with buttons producing sounds and different pitches until they turn off. The toy brought a different reaction and the boy started interacting with music.

“I sat next to him, with my guitar, a real guitar. When that [toy] was playing, I would be playing along with it. When that would stop, I would stop. We were making music together. Even though for him was just turn that on and off, it was cause and effect.” Krout had witnessed the first, meaningful response from the boy.

For Kress the first sessions are difficult because the relationship with the client hasn’t started. “The first couple of sessions are sometimes awkward. It’s hard to catch the client’s attention, to get them to behave because they’re unaccustomed to it.”

The energy saturating a session is something Krout recognized as difficult to get in other environments. The liveliness that vibrates in each session slowly disappears by the end of the 60-minute session when the group formed by those seven people decides to play the “spring song.”

On the ending note of the session, Krout takes turns dancing with some of the clients following the rhy

thm of “All My Ex’s Live in Texas” a country song by George Strait. Everybody dances and hears the music beat. Michael plays the drum; Steve pulls the strings of a guitar and listens to the sound produced. The flow of energy dissipates and the group has experienced the therapeutic process.