Sam Rodick scrolls around on Netflix looking for “Doctor Who”, hoping to continue bingeing his favorite TV show, before the realization dawns on him that the show has disappeared from the platform without warning.

It’ll be years before he can watch it again.

“Often I find that films and TV shows that I have seen on my preferred streaming platforms seem to be missing from their libraries not soon after I first see them,” Rodick said. “I sometimes feel that I spend the same amount of time trying to find the movie or TV show, as I do watching them.”

The dawn of streaming promised to end the bureaucracy of channels and commercials, replacing them with a digital Eden where complete collections of film and TV await the viewer’s every caprice. Humanity was quick to forsake the DVDs and Blu-rays of a bygone era for this superior media distribution technology.

Streaming services revolutionized the way people consume movies and TV shows. However, this advent has introduced a new financial strain on Hollywood.

Now, supplemented by the decline of DVD and Blu-Ray revenue, streaming services have started purging content from their platforms.

“If [movies and TV shows] are on streaming, that’s where they live,” SMU Professor Derek Kompare, chair and associate professor of film and media arts said.

“In the past, there’d be a lot of other stops possible along the way in the lifespan of a film or TV show. With streaming, […] that really collapses that into one [financial] path.”

For streaming, this is a smart financial plan. Removing shows that companies deem worthless can be written off as a tax deduction. However, this also destabilizes the future of movies and TV shows, pushing them closer to the border of obsoletion.

“We’re going through a return to the pre-home-video days,” Kompare said.

The Silent Era introduced the novelty of film, yet had not considered the importance of film preservation. Films were often made, distributed, and then either recycled or destroyed once they stopped showing in theaters. Due to this, the Library of Congress estimated that only about 25 percent of films from this era survive today- many of which only survived outside of the United States thanks to large-scale, accidental preservation efforts in countries like the Czech Republic.

Kompare predicts future film and media historians will face the same predicament in subsequent decades.

“It’s going to be a lot like the Silent Era,” he said. “It’s going to be like ‘well, we know this thing was made’ when you see a description and when we see a listing of it, but there are no copies available.”

SMU’s archivists Scott Martin and Jeremy Spracklen work in the G. William Jones Film & Video Collection department and are quite familiar with the struggles that accompany film’s preservation dilemma.

“The Library of Congress estimates that 75% of all silent films that were produced are no longer available, but this only highlights a tiny portion of the issue,” Spracklen said. “So many more independent, educational, corporate and industrial films that shifted tastes and human behavior have also been lost or have yet to be ‘re-discovered.’”

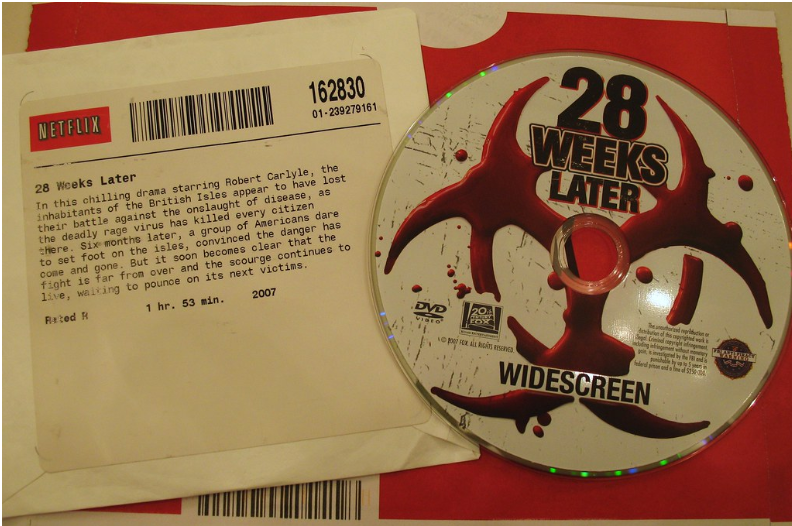

Before streaming was released for the masses, the media world was once revolutionized by VCR, and its successors: DVDs and Blu-Rays. Suddenly, the general public was no longer beholden to watching movies and TV shows during their air time or release date. Now, people can collect a physical version of the media and play it at their leisure.

“The VCR came along in the late 70s and early 80s,” Kompare said. “Now you can go to this place, rent them or buy them right and have this emotional kind of [connection]. That […] carries over into the DVD era.”

Not only did the VCR provide a multi-billion dollar industry, but it also served as a means of mass media preservation.

The plight of today’s streaming ecosystem is that DVDs and Blu-Rays exist in a precarious state. In August, Forbes reported that Disney was halting its sales of new DVDs and Blu-Rays to Australia – it had already done so with Latin American and Asian markets.

“We just assume for a long time that [DVDs] are the way it’s going to be, and that if you really care about something you emotionally invest in that you build up a collection you build a physical library like we would with books, films and TV shows.” Kompare continued. “Streaming totally blew that all up.”

Despite the streaming explosion, DVDS and Blu-Rays have clung on to some popularity thanks to a niche community of worldwide collectors.

“After [Disney halted Australian DVD sales], Disney announced that they’re releasing Mandalorian, WandaVision, and Loki on home video and DVD and Blu-Ray, which goes against what they had originally said a couple of years ago,” Kompare said.

So, what does this mean? Essentially, the future of our media is in the hands of its consumers. Media companies will follow the money.

Demanding the preservation of our media becomes especially pertinent as older digital media, that has limited or no physical copies, exists in a perpetual legal state of chaos due to streaming wars and company mergers.

“Who owns what and who is ultimately responsible for stewarding and preserving and protecting these works is a difficult knot for anyone to untangle,” Martin said.

“There’s [movies and shows] where the ownership may change and they bounce around, and it becomes uncertain who actually legally owns it,” Kompare said. “So they’re in this kind of lost zone, you know, it’s kind of a crapshoot, whether or not they’re going to survive.”

Kompare used a 90s TV show, “Homicide Life on the Street”, as an example. The show was based on David Simon’s reporting on the Baltimore Police Department’s Homicide unit. Its last physical release on DVD was more than a decade ago.

“The ownership of it is kind of in this limbo, so it’s never been on streaming,” he said. “So if you’re just looking at streaming, it literally doesn’t exist on streaming – it isn’t there.”

“So that’s the concern,” Kompare continued. “Are they ever going to come back?”

In late 2022, when journalists first started to truly report on Hollywood’s economic woes, media companies were undergoing the first of likely main streaming purges. For example, in October, streaming services removed shows like “The World According to Jeff Goldblum” (Disney), “Girl, Interrupted (1999)” (Netflix), and all four seasons of “Killing Eve” (Max) from their platforms.

Cinephiles and casual fans alike at this point may feel hopeless. The task of conserving and protecting media may feel Sisyphean. However, to save our media is to save our history. It’s an act of love.

Media is worth fighting for.

“Our moving image history reminds us of what we liked and what we were like, for better or worse,” Martin said. “I think that’s the benefit of all this: connecting us in a direct way to our stories that is immediate and relatable and intensely empathetic.”

SMU’s archivists see several pathways to helping preserve our digital media. They suggest backing up any digital home projects and supporting physical media when possible.

“A good personal rule is if it’s a movie you like, buy the physical copy if you can,” Martin said. “Also consider donating all your physical media and digital files to an archive,” he said.

Kompare also has advice for the next generation of media consumers. He says that students should try to learn about what will happen to their favorite media and pressure companies to protect what they have.

“Anything [students] are interested in, they have to look into what’s going to happen to it,” he said. “None of this preservation happens just by nature.”