Three minutes of pure darkness.

That’s what most people think of when they conjure up the image of a total solar eclipse.

In reality, the celestial event, and its earthen celebrations, have a history of being a bit more lively.

To better understand the relevance of this particular eclipse, The DC sat down with physics professor Joel Meyers to understand more about the significance of this epic astronomical event.

“Humans have been studying eclipses […] even before written records,” Professor Meyers shared with the DC. “One of the earliest eclipses that we think has a record was observed in 3300 BCE […] by people in Northern Ireland.”

Meyers explained that mankind has a long history of seeking to find their place among the sky and stars.

“What goes on in the sky […] is very visible to a lot of people. That has inevitably influenced the culture and the way that we try to understand our place in the universe.”

In 2017, the SMU Physics department hosted a flock of students, staff and spectators to view the partial solar eclipse on Aug. 21 of that year.

But this is nowhere near the first time SMU has celebrated a solar eclipse.

In February of 1979, Dallas saw another total solar eclipse.

More than four decades ago, a small group of SMU students, backed by contemporary professors Charlie Ballison and Harold Blum, held their version of a watch party on campus.

Why is Dallas seemingly a prime location for eclipse viewing? Meyer says this circumstance is purely coincidental.

“The northern hemisphere gets more total eclipses than the southern hemisphere, which has to do with just the tilt of the earth and where the landmass is basically.”

Though Dallas tends to lie in the path of prime viewing for eclipse totality, it’s important to cherish the scarce and sacred nature of this otherworldly episode, Meyer said.

“Total solar eclipses are relatively rare. The last total solar eclipse visible from anywhere in the contiguous 48 states was 2017, and the next one after April 8, won’t be until 2044,” Meyers said.

Though Ballison and Blum’s eclipse viewing in 1979 was mainly for pleasure, they still queried if the eclipse would affect temperature or illumination changes in Dallas.

“Total solar eclipses offer even more opportunity for scientific investigation than partial eclipses,” Meyers explained.

In 1979, Professor Ballison charted the moon’s movement across the sun, and Blum measured the sun’s radiation at various stages.

“The sun has a very strong influence on the weather […] however, it’s very difficult to do experiments where you can turn off the influence of the sun,” Meyers explained. “Eclipses offer a natural sort of natural experiment […] to see what happens when the effect of the Sun is locally turned off in some regions and to determine then how the atmosphere responds both in temperature and pressure and wind speeds.”

“You’ll notice during the total solar eclipse that [the] temperature will noticeably drop,” Meyers said.

This year, the SMU physics department plans to project an image of the eclipse into the rotunda of Dallas Hall via telescope, to allow for optimized viewing, even for students who don’t have eclipse glasses.

“We will record the Eclipse and do some astrophotography with the video and images we take from that. There will also be some physicists on him answering questions about the Eclipse,” Meyers said.

These viewing festivities have drastically evolved from the mirror projection on a home movie screen utilized by Dr. George Crawford in 1979 to help eclipse viewers observe the phenomenon.

The curiosity about celestial bodies shared by the eclipse spectators of the 1970s is not unlike our modern-day inquisitiveness.

“Just to see it alone awakens the imagination,” Dr. Crawford said to KXAS/NBC Fort Worth reporter Pat Couch at the time of the 1979 eclipse. “One begins to ask the question: ‘How does the universe actually move?’”

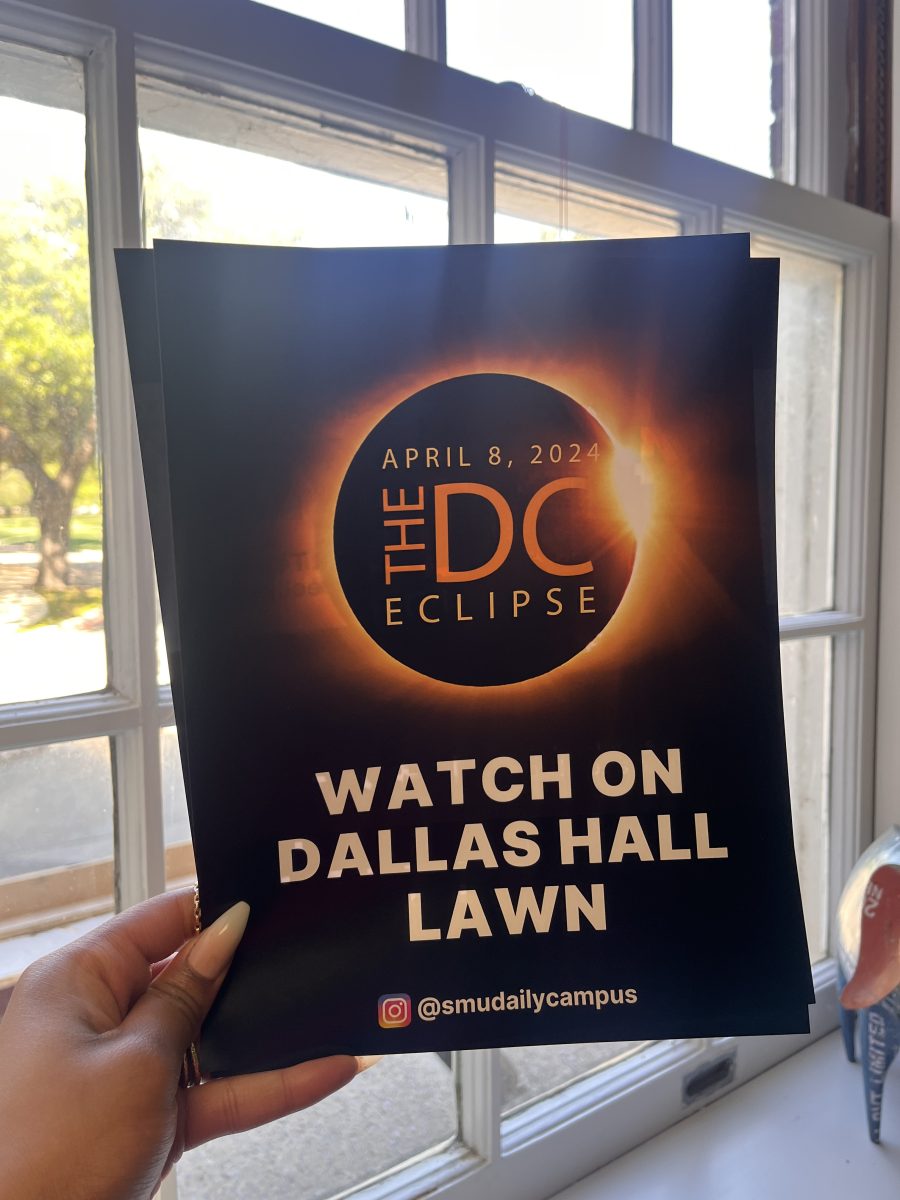

On April 8, the solar eclipse totality will begin at 1:40 p.m. and last approximately three minutes. There will be a host of festivities on Dallas Hall Lawn presented by the SMU Physics department as well as by The DC to celebrate the dawn of another eclipse on the Hilltop.

“I strongly encourage everyone to step outside to experience the whole eclipse, not just the four minutes of totality around 1:40,” Meyers emphasized.

Stay up-to-date with eclipse news on the DC’s Instagram @smudailycampus.