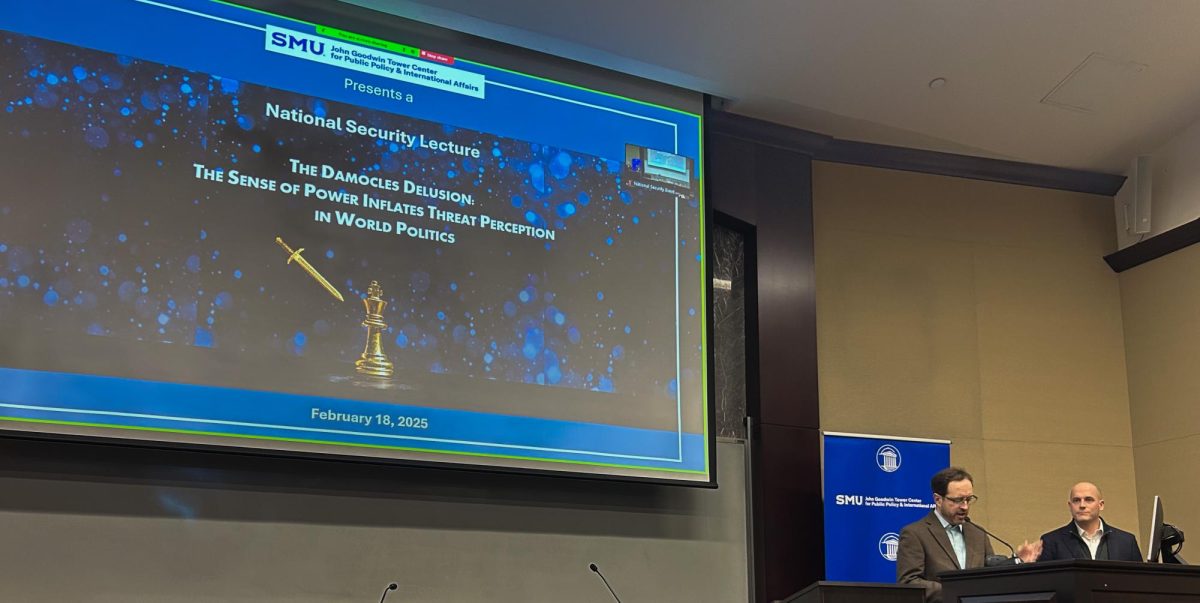

Commanding the attention of a full audience, Caleb Pomeroy spoke about the dynamic between power and individuals’ threat perceptions in the Walsh Room at SMU’s Underwood Law Library on Feb. 18 at the SMU Tower Center’s first National Security Program event of 2025.

Pomeroy boasts an impressive resume as a published researcher and assistant professor of political science, global affairs and public policy at the University of Toronto. His rapt audience laughed, grumbled and sighed along with Pomeroy as he led them through a rather daunting analysis of the psychology of power and its tangible impacts on international relations.

Starting with an explanation of power, defined as relative capabilities, specifically military and economic strength, Pomeroy asserted that “power paradoxically makes leaders worse at power politics.”

Jumping straight to the impact of his argument, Pomeroy noted increased objective power has an inverse relationship to psychological security.

“Why do we care about the psychological effects of power,” Pomeroy questioned. “Well, as [Stefano Recchia] mentioned, a basic premise of international relations is that the stronger you are, the safer you should be. And it turns out in psychological terms, it’s exactly the reverse.”

Drawing from a 2021 survey of 880 adults in Beijing, Pomeroy found that persons assigned high levels of respective power had higher threat perceptions than those assigned low levels of power, despite both groups being presented with an objective level of threat.

From a series of interviews in 2020 with 245 Russian elites, Pomeroy discovered that there is a positive correlation between perceived power and perceived national security threats.

“If you feel that Russian power is on the rise, you’re more certain that the U.S., NATO, and Ukraine pose a security threat to Russia,” Pomeroy said.

Pomeroy ended his presentation by calling attention to the United States and China, suggesting that both countries see themselves as superior powers which could perpetuate heightened threat perceptions leading to mutual harm.

Faced with Pomeroy’s unsettling conclusion that those in power fall prey to skewed threat perceptions, attendees were eager to ask Pomeroy questions.

Stefano Recchia, the director of SMU’s Tower Center National Security Program and event moderator proposed one alternative explanation.

“States that are powerful might feel dissatisfied with their recognition that they get from others in the international system,” Recchia said. “You’re not getting what you’re due and so that makes you view others as hostile and potentially threatening.”

Sophomore Victoria Valderrey asked Pomeroy if embracing democracy worldwide to lower threat perception could be a solution in international relations. While others, like Kevin Dou, alluded back to the U.S. and China relationship asking, “If you were to be an advisor advising members of the Politburo and you’re aware of the phenomena you were just discussing, what tweaks would you add to the briefing process.”

Overall, Pomeroy offered a closer insight into current political affairs that allows students to better analyze current global events.