Editor’s Note: The following is Part 1 in our “Hidden on the Hilltop: SMU’s Culture of Secrecy” series, which examines the secretive nature of various operations at SMU.

For the rest of the series: Part 2a, Part 2b, Part 3, Part 4

On the same day that head coach June Jones and the football team strode aboard a chartered 767 bound for Hawaii and the university’s first bowl game in 25 years, SMU President R. Gerald Turner glumly reported college football was in crisis. Worse yet, Turner wrote in a Dec. 19 Washington Post editorial, the business of college athletics “is on a path toward meltdown.”

Turner said he and other college presidents could avert financial catastrophe only if they went public with athletic budget information. In Turner’s words, “The first step will need to be true transparency regarding athletic spending.”

SMU officials have yet to fulfill this promise.

Despite repeated attempts by The Daily Campus in late January to get basic revenues and expenses for the SMU Athletic Department for the past five years, officials declined to release any information. Brad Sutton, assistant athletic director for media relations, said,

“The department does not do that.” Travis Wolther, the department’s manager of financial reporting, called the budget “confidential information.”

Turner told The Daily Campus athletic officials should give budget information to campus groups with what he called “leadership responsibilities.”

“If you’re writing an article, we’d have it available,” he said. “Whether it’s just out to be wallpaper somewhere, I don’t have any desire to do that.”

Some students have a problem with the restricted access to the budget.

“I think it should be available to all students since we pay so much to go here,” sophomore Jenny Pender said.

Other students questioned why SMU wants to keep the information so quiet.

“Anything that’s kept so confidential seems strange,” senior Courtney Jones said.

Using the SMU Faculty Senate Web site, The Daily Campus independently obtained athletic department records for the past six years. They show that during those years the SMU Athletic Department lost more than $93 million. This is equal to 40 percent of all tuition and fees paid by students in 2009.

Some students said they were stunned by the losses. “That’s shocking,” freshman Alex Williamson said.

It wasn’t supposed to be like this. When Turner hired Steve Orsini as athletic director in 2006, one of his main goals was to improve the financial situation of the athletic department, Orsini recalled in an interview. Orsini, a former CPA, had the “business expertise that will help us build resources and fan support,” Turner said. Since then, the financial situation of the department has changed – for the worse.

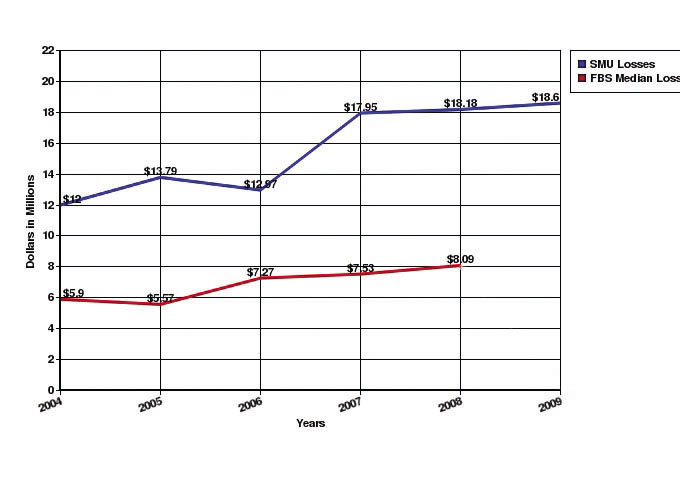

From 2004 to 2006, before Orsini was hired, the department’s annual deficit ranged between $12 and $13 million. Since Orsini’s first full year at SMU in 2007, annual athletic department losses have ballooned to $18 million annually – a 50 percent increase. This jump in losses is something Orsini says he can’t explain.

“I can’t answer that,” he said. “I don’t know.”

Most college athletic programs lose money, primarily because of football. What’s different about SMU is that the athletic department loses a lot more money than most.

A 2009 NCAA report looked at SMU and 118 other Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) schools. Ninety-four lost money. The median deficit for these 94 colleges was $7.27 million in 2006, $7.53 million in 2007 and $8.09 in 2008. By comparison, the SMU Athletic Department lost $12.97 million in 2006, $17.95 million in 2007 and $18.18 million in 2008—more than twice the median deficit for the 94 schools.

Despite the athletic department’s refusal to provide this information, Turner said the figures are readily available for interested parties such as SMU students and their parents.

“The issue on transparency is, ‘Are the basic components of the operation of your athletic program made available to the constituents of your campus?’ And our answer is yes here,” he said.

A search of the SMU Web site suggests otherwise. The athletic department site contains no budget information. A search of SMU using “athletic deficit” turns up scattered references to the department’s losses. But in virtually every case, these figures—reported by SMU administrators to the Faculty Senate—are significantly lower than the department’s actual losses.

Orsini and other officials told the Faculty Senate in October 2008 the athletic deficit for the past year was $7.4 million, not $17.95 million. In April 2009, the athletic department told a Senate panel its 2008 deficit was $7.2 million, not $18.18 million. That same month, the department told the Faculty Senate its estimated 2009 deficit was $6.3 million, not $18.6 million as reported on university budget documents.

How do Orsini and other administrators come up with these figures? At SMU, athletic scholarships count for roughly a third of the athletic department’s expenses due to the high cost of tuition. Orsini, with the support of top SMU administrators, does not count athletic scholarships as an expense for his department. “What the university says is: ‘We’re not burdening the athletic department with that,’ ” Orsini said.

The NCAA includes scholarships, or grants-in-aid, as an athletic department expense. So does the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics, a national watchdog group seeking to reform college athletics. Experts who have spent years studying the business of college athletics—including Dan Fulks, a Transylvania University accounting professor and research consultant for the NCAA, and Jay Weiner, a sports journalist and author of a recent Knight Commission report—said scholarships should be included when calculating the bottom line for athletic programs.

“Grants-in-aid are an expense, indeed,” Weiner said. “Across the Football Bowl Subdivision they account for 16 percent of athletic departments’ costs.”

Few know this subject better than President Turner, who has co-chaired the Knight Commission since 2006. He said it is accurate to include scholarships as an athletic department expense. “Yes, it is fair, absolutely,” he said.

Fulks and other experts said universities often use student fees or tuition increases to help cover the costs of athletic deficits. In 2008, student fees across all FBS schools (those comparable to SMU) accounted for 6 percent of the median total revenues for athletic programs, according to a 2009 NCAA report Fulks authored.

“Students should be well aware of what it costs the university to operate the athletic program and what it costs them directly through student fees,” Fulks said.

“College Sports 101,” a recent report by the Knight Commission, points out the dangers of taking money from a university’s general fund and putting it into athletics.

“With costs in athletics rising faster than in other areas of university operations, it is not clear how many institutions can continue to underwrite athletics at their current level without allocating significant funds that could be used for teaching, research, service, student services, or other core functions,” the report states.

Political science professor Matthew Wilson, who sits on the Faculty Senate’s Athletics Policy Committee, echoed this concern.

“Every dollar that subsidizes athletic operations could be subsidizing new faculty positions, or scholarships for students, or research infrastructure and grants,” Wilson said.

Weiner said colleges usually say little about this. “Most students or parents don’t know of these shifts from central funds to athletics,” he said.

Students at SMU were no exception.

Senior advertising major Caroline Hill was angry her tuition helps pay for a program that loses $18 million a year.

“That makes me upset,” Hill said.

Williamson said he now realizes why he has to pay so much to attend SMU.

“Well, now I know where more of that big tuition goes,” Williamson said.

According to Orsini, there was no conscious effort to increase spending when he started as athletic director. However, expenses, not including scholarships, increased from $13.7 million in 2006 to $21.3 million in 2008 – a 55 percent increase.

SMU is not alone. In October 2009, the Knight Commission interviewed university presidents across the country about the hidden threat posed by athletic deficits. Several expressed concern about the spike in athletic spending. One put it this way: “The problem is, it’s such big money. It’s an arms race that’s self-perpetuating.”

The Commission found that eight out of 10 university presidents agreed with Turner’s call for transparency, meaning readily available budgets that also are accurate.

Weiner said not having a full understanding of athletic department expenses allows deficits to skyrocket.

Some SMU students did see an upside to the increasing deficit.

“I don’t think it’s a horrible thing,” senior finance major Megan Tague said. “It sucks right now, because our teams aren’t good, but if our degrees are going to mean more in the end, then it’s OK.”

This is a way of looking at athletic departments as investments to attract students and faculty to the university, Orsini said.

“Athletics is like a front porch to a home. You don’t have to have a front porch to have a nice home, but if you’re going to have a front porch, have it look attractive so people will want to check out your home. In this case, having an athletic program that’s attractive to potential students that may want to come to SMU,” Orsini said. “Universities are willing to invest in that aspect to get a return, which is more people wanting to come to your school.”

Fulks said the real area of concern that they have found at the NCAA is the growth rate in spending.

“We don’t want athletic spending to grow any faster than the entire university’s spending,” Fulks said.

Between 2007 and 2008, records show, total university expenses at SMU grew 9.6 percent, while total athletic expenses grew 20.5 percent.

Orsini said he hopes that an increase in wins by sports teams, like football, will bring in more revenue to curb the costs of the department. He said the deficit is still a concern of his and Turner’s, just like whether or not a team is winning.

“It’s an ongoing evaluation about lowering the support of the university towards athletics,” Orsini said. “We talk about that just like we talk about, ‘Hey, the men’s basketball program lost a tough one last night.’ It’s an ongoing challenge, just like wins are.”

SMU estimates that in 2010, its athletic department will lose another $18 million.

The blue line represents the SMU Athletic Department deficit in millions. In 2007, Athletic Director Steve Orsini’s first full year at SMU, losses ballooned to $18 million – a 50 percent increase. The red line represents data from an NCAA report that looked at SMU and 118 other Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS) schools (formerly known as Division 1-A). Ninety-four lost money. However, SMU’s athletic deficit has been more than twice the median deficit for the 94 schools since 2007.