Crowds of children dressed as Disney princesses, hippies and TV stars swarm the streets of neighborhoods to trick-or-treat every year on Oct. 31, in an effort to acquire as much candy as possible.

Yet, roughly 2,000 years ago, it was likely that people stayed indoors to avoid crossing paths with ghosts and witches, who were returning to Earth on the darkest night of the year.

Originating as a mix of ancient Celtic practices, Roman Catholic religious rituals and European folk tradition, Halloween has transformed over the years from a Pagan festivity into a secular holiday.

The Celts, who lived in modern day Ireland, Scotland and France, celebrated their new year Nov. 1, which marked the end of summer and the harvest as well as the beginning of winter in the Gaelic calendar.

However, historians can only speculate about what took place on the night of Oct. 31.

History Professor Jeremy Adams had one speculation of what it was like.

“It was a special and strange time,” he said. “It was the night that the doors between the two worlds stayed open, and peoples’ bodies and souls could pass back and forth,” he said.

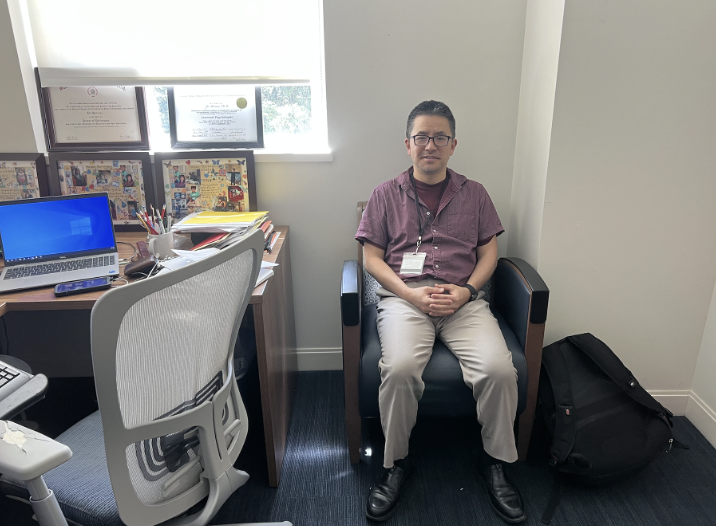

Trick-or-treating may have originated from a method to avoid lingering spirits, according to SMU Sociology Professor Adrian Tan.

“Since spirits would roam the Earth, many would leave treats outside by their doorway to deter spirits from coming in,” Tan said. “They would also dress their children as ‘demons,’ so that spirits would skip entering their homes thinking that there were other spirits already in their house.”

The night before the new year, Oct. 31, the Celts celebrated the festival of Samhain (pronounced sow-in).

Samhain, which means “summer ends,” was celebrated over several days, marking the end of the lighter half of the year and the beginning of the darker half.

Hence, the thematic colors of black, representing the night and darkness, and orange, representing the changing colors of the leaves, were born.

Some say that ancestors, in the form of ghosts and witches, would come back to Earth to sanction law cases that were unsettled.

“It was a big day of reckoning,” Adams said. “It’s always been spooky.”

Others believe that the Celts would wear animal skins and ghost masks while gathering around bonfires, making animal and crop sacrifices in honor of the fertility Gods.

The Celts were superstitious, believing that the spirits killed their crops and helped the Druids, Celtic priests, tell the future.

The Druids were more than just Celtic priests; according to Adams, they were also legal experts. Druids were among the few who walked from house to house settling legal cases on the night of Oct. 31.

Though Adams is unsure where the tradition of trick-or-treating originated, he believes it is possible the Druids and other legal experts might have collected treats from the houses they visited as a fee for their legal expertise.

Roman occupation, from 40 AD to 475 AD, as well as the spread of Christianity, influenced the Celtic traditions.

The modern tradition of bobbing for apples was most likely the result of the combination of Samhain and the Roman’s Pagan Festival of Feralia. During this festival, the Goddess of Pomona, whose symbol is the apple, was honored.

In the seventh century, the Roman Catholic Church, under the reign of Pope Boniface IV, declared Nov. 1 All Saint’s Day and Nov. 2 All Soul’s Day in order to incorporate Christianity into what was then a solely Pagan festival.

“[All Saint’s Day] was the Christian reverence to the dead,” Adams said. “It competed with the Celtic holiday of the previous night.”

All Saints’ Day was commonly referred to as All-Hallowmas, making the Celtic celebration Samhain All-Hallows Eve, which eventually became Halloween.

Halloween disappeared during the Puritanical period of the 16th and 17th centuries, because “it was seen as the work of the devil,” Tan said.

However, in the second half of the 19th century, millions of immigrants, especially the Irish, fled to America, bringing with them their Halloween rituals.

According to some people, modern-day trick-or-treating stems from the Irish’s tradition of dressing up and going to different houses asking for food or money.

Superstition also came to America with the Irish and Scottish belief that on Halloween, women could foresee their future husbands, according to Tan.

Scottish women would write “their suitor’s name on hazelnuts and would throw them into the fireplace. If the hazelnut burned without popping, the person whose name is on the hazelnut is the future husband,” Tan said.

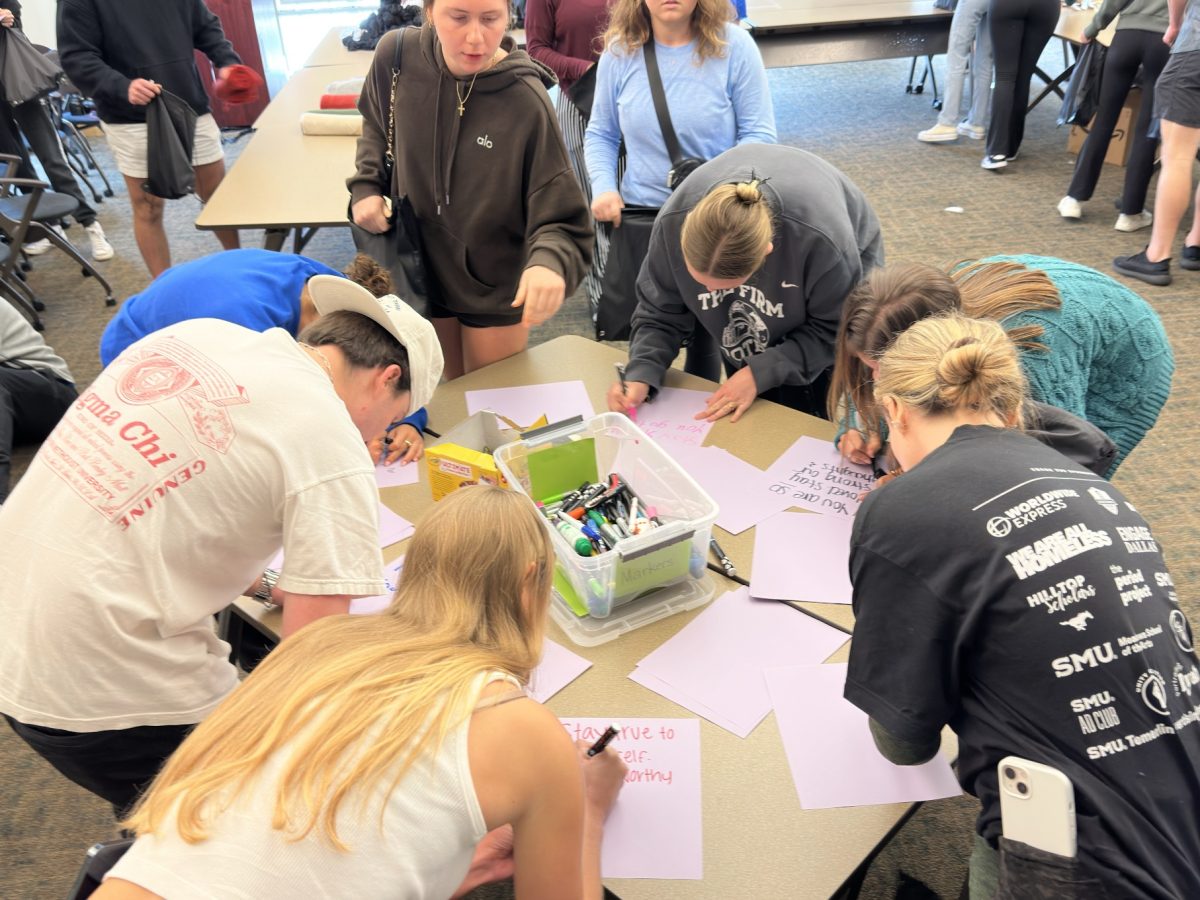

However, in the late 19th century and early 20th century, the focus of Halloween turned from ghosts and witchcraft to festive parties, where dressed-up children and adults could gather to play games, such as bobbing for apples.

With this change, Halloween began to lose its religious and superstitious ties to the Celts.

By the 20th century, Halloween was a secular holiday celebrated within communities and schools. Vandalism and crime became an issue in relation to Halloween and is still an issue today with theft and pumpkin smashing.

With the rise of consumerism in the 1930s, stores began selling mass-produced Halloween costumes. SMU junior Kendra Eaton already has her outfit planned.

“I can either be creative with my Halloween outfit and make it myself, like I am this year, or I can go to a Halloween store and buy one,” Eaton said. “This year Sarah Grayden and I are reppin’ our hometown by dressing as Lakers girls.”

While adults and children still enjoy dressing up, some even go as far as dressing up their pets.

Junior Phoebe Berndt plans to buy her dog, Addy, her first Halloween outfit this year.

“My dog’s nickname is ‘Addygator,’ so I am thinking of dressing her up as an alligator,” Berndt said. “I already have the outfit picked out.”

According to the National Retail Foundation (NRF), the No. 1 costume for adults is a witch, which goes back to the Celtic beliefs, while the No. 1 costume for children is a princess.

Halloween is the country’s second largest commercial holiday, after Christmas, with consumers spending an estimated $5 billion in 2009, according to the NRF.