Law clinic assists needy (Photo by Austin Kilgore, The Daily Campus)

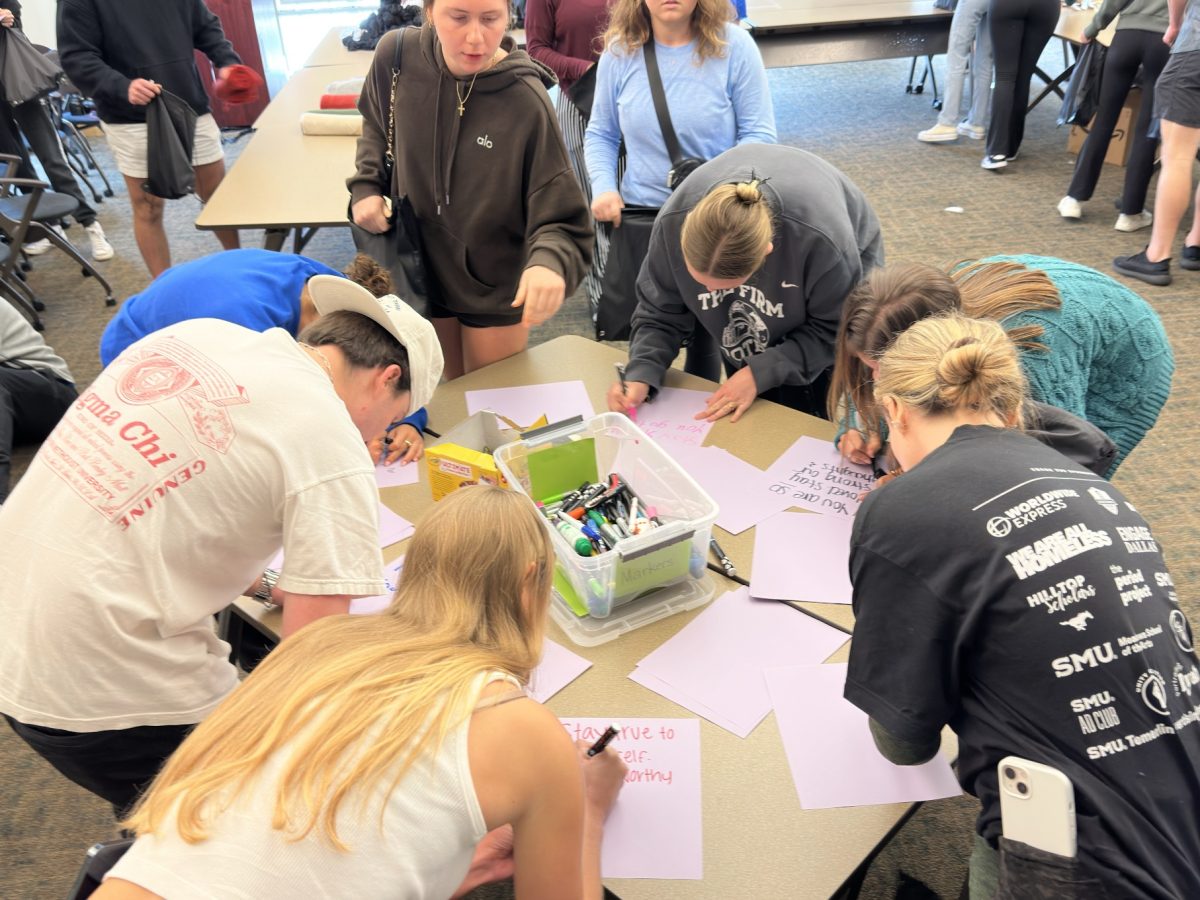

Unbeknownst to most of the undergraduates here, the basement of Storey Hall hides a well-kept secret: the SMU Legal Clinics. The clinics provide legal aid to members of the community that cannot afford other representation. Each semester approximately 50 applicants are chosen to participate in this class that takes the students far beyond the classroom.

Each clinic has the same prerequisites – 45 credit hours of law classes, specifically including the course “Evidence” – and students are assigned to the clinics by a lottery system. Applicants rank the clinics in order of preference and all the names are put into a metaphorical hat. The first name chosen receives his first choice clinic, and so on until all of the spots have been filled.

The Criminal Justice Clinic takes on 12 students each semester for the criminal defense class under the supervision of Associate Director Mike McCollum, LL.B., and two other supervising attorneys. Unlike some introductory classes, there is no shallow end to this course.

“The second week we were here I got to try a case in front of a jury. I didn’t think I would ever get to do that in my whole career,” Rashee Raj, a second-year law student in the Criminal Justice legal clinic, said.

Typical caseload for a student in the clinic is 12-15 misdemeanor cases at any given time, according to current participating students, and include cases of D.W.I., possession of marijuana, indecent exposure and assault. The student attorneys have to go to the courts and request new cases for themselves when their caseloads are looking light.

Students in the Tax Clinic, overseen by Director Larry Jones, J.D., on the other hand, usually handle about eight clients at a time, each of them having issues to resolve with the IRS. Cases range from audits to appeals of previous rulings to collection issues, but whatever the case, the goal of the Tax Clinic is to resolve the cases before they go to court.

Some cases can be resolved fairly quickly, but collection cases involving frozen bank accounts and garnishment of wages can be more complicated.

“Collections cases take longer … there’s more fact-finding,” Monica Parish, a third-year law student and one of 10 student attorneys in the Tax Clinic, said.

The biggest clinic by far is the Civil Clinic, run by Co-Directors Maureen Armour, J.D., and Mary Spector, J.D., which accepts 20 students every semester and divides them into two groups, each group reporting to its own supervising attorney.

Civil litigation includes things like landlord-tenant disputes, civil rights cases and consumer cases. The class meets twice a week to learn about the body of law that relates to the types of cases they are working on.

Though the actual class material varies by clinic, all course grades are based on performance, which includes everything from research to speaking before a judge and jury. But at this point, this isn’t just a class and for these students and it’s not just about the grades.

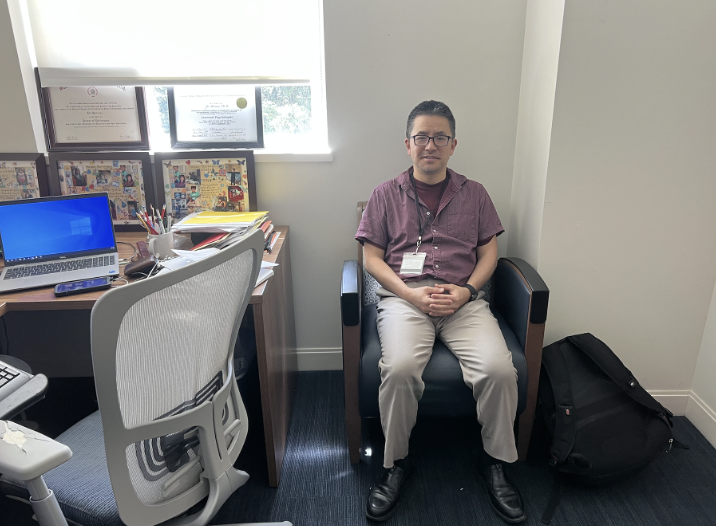

In the W.W. Caruth, Jr. Child Advocacy Clinic, headed by Director Jessica Dixon, J.D., the student attorney’s representation can literally alter the entire course of the client’s life—their clients aren’t adults, like in the other clinics, but children.

Once Child Protective Services removes a child from the home, usually for neglect or abuse, the court has up to 48 hours to appoint a guardian ad litum, or someone legally representing the child. In this case, the student attorney becomes the child’s voice in the courtroom.

Within 14 days of removal, a court date must be set where the state must either prove its case or return the child to its parents. During those 14 days, the child’s attorney researches the family’s history, interviews the parents, child and any foster parents, as well as supervises visits between the parents and child.

As guardian ad litum the attorney’s sole job is to find out and advocate the best interest of the child.

“The ultimate goal is to place the child in some sort of permanent setting,” Nick Peters, a second-year law student working in the child advocacy clinic, said.

Photos of smiling children lining bookcase shelves testify to the lasting impact the attorneys have on the community, but the children aren’t the only ones affected by the work of the clinics. Third-year law student Adrienne Ellis graduates this May and plans to go into commercial litigation at Kerrington Coleman, but says she would love to do child advocacy as her pro-bono work.

Though the students in the clinic have not graduated, they are getting a chance to really practice what they have spent years learning about in the classroom.

“Everything is so theoretical to this point … then you realize it’s all do-able,” Nisha Moreau, a third-year law student in the Civil Clinic, said.