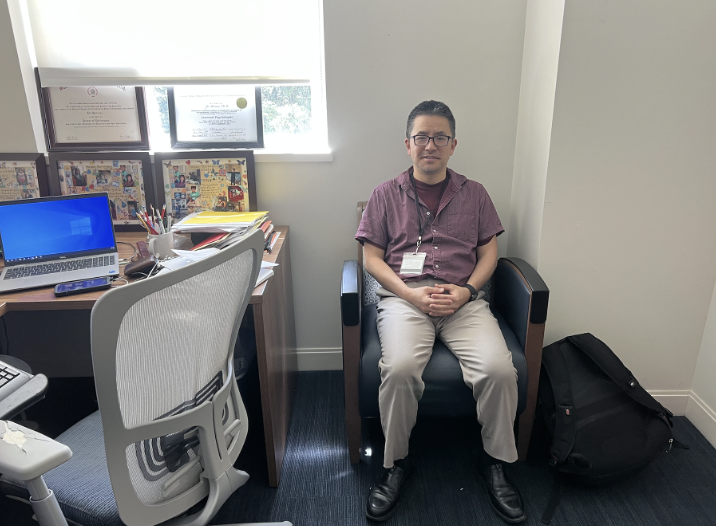

Kael Alford, an adjunct Meadows professor, is a photojournalist. (Courtesy of Photowings)

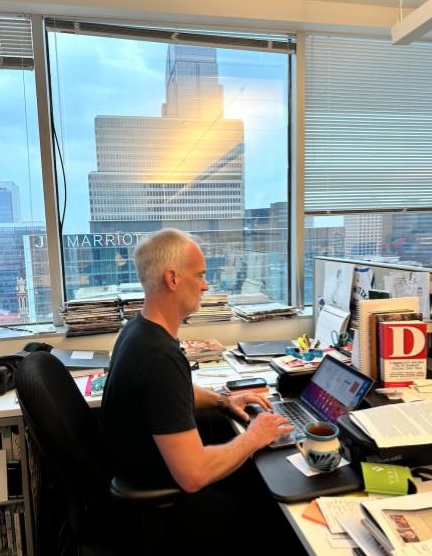

Although the Meadows School of the Arts sometimes seems like a world of its own, for adjunct professor Kael Alford it’s just another pit stop on a never ending journey across the globe.

Before coming to teach at SMU, Alford went from the Balkans to the Netherlands, and finally to Iraq before returning to America. Her return, however, was not a mark of slowing down.

“I was kind of a restless person – always pushing the boundaries of any social situation I was in,” Alford said.

This restlessness has been a defining characteristic of Alford’s career as a documentary photographer, writer and journalist. It even affected the way Alford chose her professional pathway, which didn’t necessarily begin with the idea of photojournalism.

“I always imagined I would be a writer. I still think of myself as a writer,” Alford said.

Alford specialized in English and anthropology at Boston University, but eventually went on to achieve her masters in journalism at the University of Missouri. It was during the latter half of her higher education that Alford grew to enjoy photojournalism.

However, Alford’s choice to pursue documentary photography wasn’t a complete surprise.

“When I was young, I was always exploring my neighborhoods – anything in walking distance. The exploration in my childhood made me interested in photojournalism as a career.”

The theme of exploration runs through the catalogue of Alford’s work: particularly her photography documenting the Iraq War and soil erosion on the Louisiana coastline. Both series attempt to uncover a side of the story that may not be accurately represented in the media. These stories, though nearly invisible to the outside world, get airplay through Alford’s lens.

“I think her philosophy is that of what I consider to be the great documentarians, which is make the unseen visible through whatever it takes,” professor Michael Corris said.

To get a good grasp on the unseen, Alford has employed extreme measures in the past. For her photography during the Iraq War, Alford managed to negotiate a visa at the consulate in Jordan three weeks before the invasion of Baghdad.

When asked why she put herself in such danger, Alford emphasized the importance of shedding light on both sides of the issue.

“There’s the story the government tells about what’s happening on the ground, and you can count on that narrative being false in some way or another,” Alford said.

Although the situation in Iraq called for a distrust of the local government, Alford’s work in the Pointe-aux-Chenes and Isle de Jean Charles areas of Louisiana point to a much more personal connection.

“[Her] position is one that’s politically informed, but she’s looking at the areas not getting a lot of media coverage. She’s drawn to those areas,” Corris said.

The unseen element of Alford’s work in the Gulf includes the forgotten Native American and French populations that still reside on the disappearing lands. Alford can trace her heritage to these populations through her maternal grandmother’s family and her work resonates with an attachment to the fading area.

“These are places literally washing out to sea. I like to imagine this is as a footnote of these communities’ history,” Alford said.

While Alford’s freelance work and personal projects have taken her to a mix of countries across the world, her photography is meant to wade through the confusion of conflict and provide a glimpse into the lives of civilians on the ground.

“Her ability to find the human element and spirit amongst decay, destruction or chaos is a gift,” teaching assistant William Binnie said.

When it comes to the photographic process, Alford admits the limits of her journalistic training.

“Journalism’s more limited because of the contract between the audience and the photographer. The audience needs to know you’re not intervening in any way,” Alford said.

This shift from documentary reporting to a more personal approach comes to light between Alford’s two books Unembedded and Bottom of ‘da Boot – which focus on Iraq and Louisiana respectively.

“[Alford is] not afraid to get out and go somewhere. That’s my idea of documentary photography in the context of journalism,” Corris said.

Alford’s time is currently consumed by her responsibilities as an adjunct professor, her project on the Louisiana coastline and workshopping around the country. Regardless of her time commitments, however, Alford remains dedicated to exploring mysteries in the world.

“Artists do what they do because they have questions they want to answer. Art gives them the space to explore those possibilities,” Alford said.