Pictures from five decades ago line the walls of a new exhibit at the Dallas Holocaust Museum. Among the paintings are renditions of dormitories in the Jewish ghettos, underwater worlds, quaint cottages, and dreams of home. These are the drawings of children confined in the Terezín ghetto.

The museum on Record Street has opened a new exhibit, “Every Child Has a Name,” which details the experiences and suffering of the 1.5 million children who were hauled off to brutal concentration camps.

Founded in 1984 to educate the community and commemorate the lives of the 6 million Jews who were slaughtered after being tortured, malnourished, experimented on, and separated from their family members, The Dallas Holocaust Museum allows viewers to examine the horrors of genocide.

The section of the exhibit titled “No Child’s Play” provides viewers a glimpse into the lives of Jewish children. The section features toys children played with prior to the Holocaust and while confined in ghettos, including teddy bears, hoola hoops, Mickey Mouse dolls, wooden toys, and a Monopoly set.

Another section of the exhibit consists of pennies arranged in tubes of varying sizes, used to represent each child who lost his or her life in the Holocaust.

The penny collection started in 2006 with a group of students from Memorial Preparatory School in Garland and soon became a city-wide effort. The museum finally reached its goal of 1.5 million pennies last fall, but officials quickly realized the sheer volume of pennies would overwhelm the Dallas Holocaust Museum’s small building. The majority of pennies now sit in a vault in the bank, but 117,000 fill the tubes in the exhibit.

Julie Meetal, the artist behind the penny structure, explained that the tubes are fashioned to represent the smoke stacks so synonymous with concentration camps.

“The number is lost sometimes, because its just a number,” said Meetal. “We wanted to show what that actually looks like.”

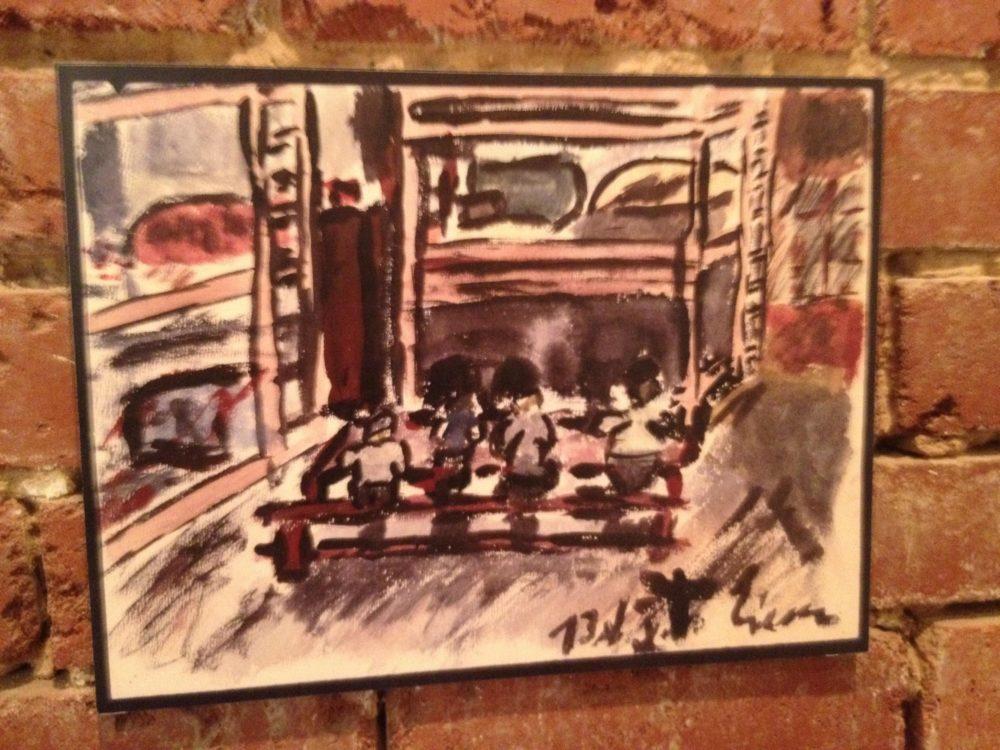

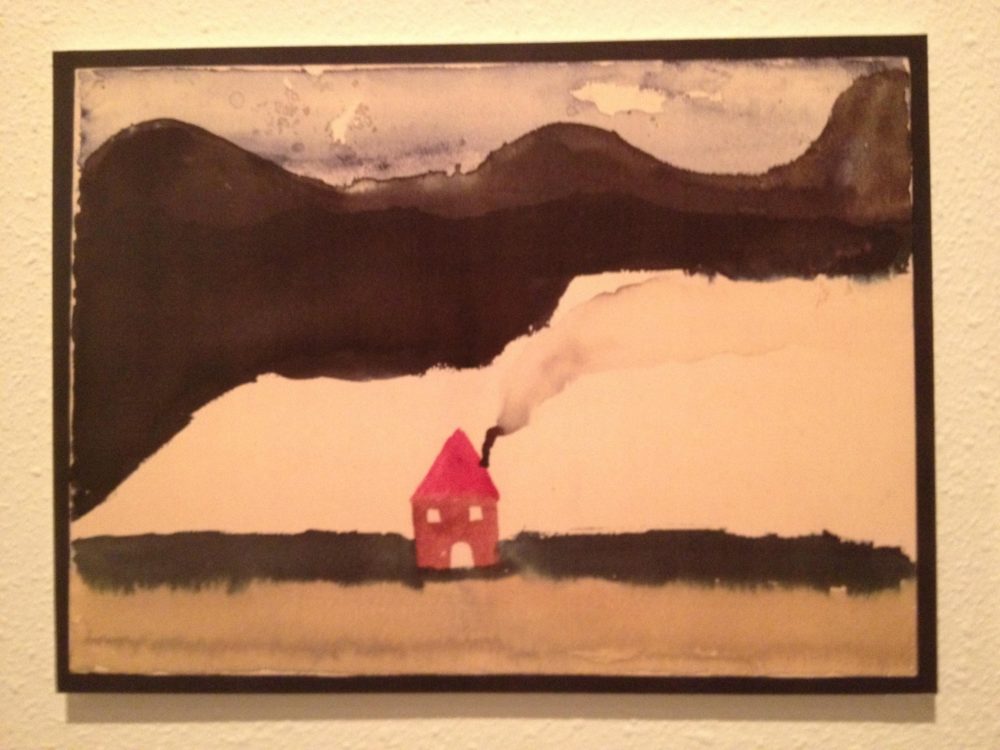

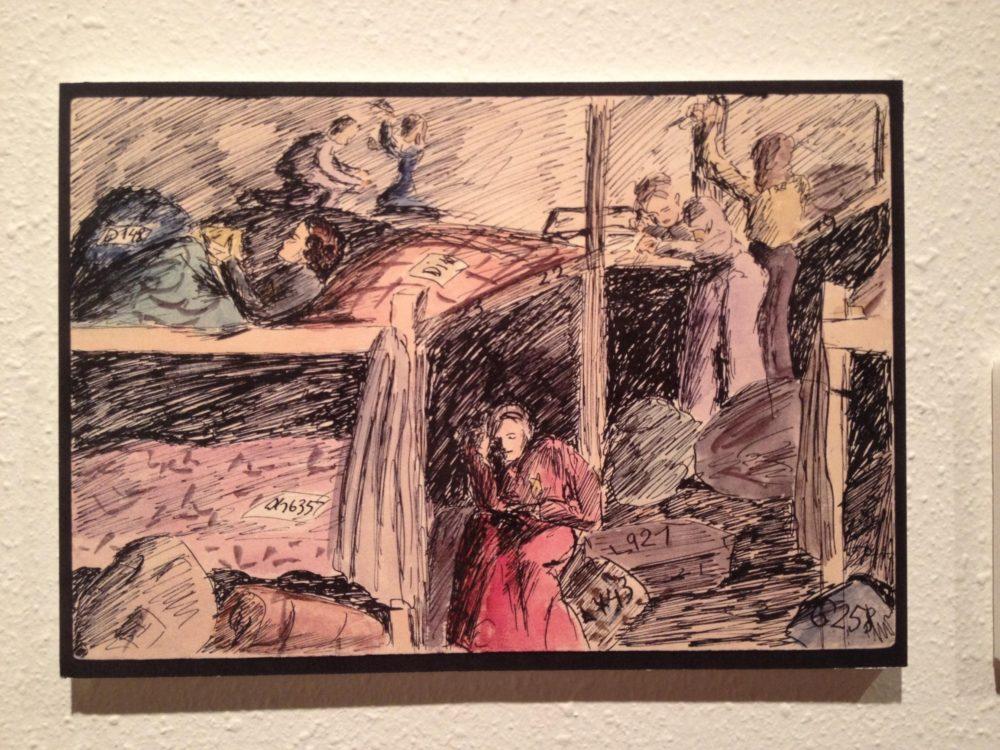

The third installment in “Every Child Has a Name” is a collection of artwork and poems from the children of the Terezín ghetto in Poland, which was home to approximately 15,000 children between 1942 and 1944.

To distract from the horrors of war and provide a semblance of a childhood for these thousands of displaced children, the adults there created a school. Under the Nazi regime, only crafts, drawing, and singing could be taught, but slowly, sciences, history, languages, and literature crept into the curriculum under the radar.

When Friedl-Dicker Brandeis, a drawing instructor at the school, was selected for transport to a concentration camp in 1944, she hid two suitcases full of the children’s artwork and poetry, which were brought to the Jewish Museum of Prague after the war ended.

There they sat for ten years, before they were rediscovered and displayed.

Museum-goers are enveloped in art as they enter the small room, with walls splattered with reproductions of paintings and sketches. Speakers softly play a score of the opera “Brundíbar,” written by Hans Krasa, a prisoner of Terezín.

Rick Halperin, director of SMU Embrey Human Rights Program and chair of Amnesty International USA, describes the exhibit as not only moving, but also timely.

In an interview in his cluttered office on campus, Halperin explains that the great phrase that came out of this tragedy was “never again.” This begs the question: Why have the horrors of the Holocaust not vanished? Almost seven decades later, genocide still occurs, he said.

Similar abuse, maltreatment, and cruelty inflicted by adults on infants and children has happened since in places like Rwanda and Cambodia and currently in Darfur.

Because genocide is still an issue in today’s world, the Dallas Holocaust Museum’s Director of Education and Programming Kathy Chapman created a “Holocaust/Genocide/Tolerance” curriculum for teachers.

In addition to teaching the Eight Stages of Genocide, the curriculum promotes respect for individuals and aims to prevent polarization and bigotry.

“Because of the amount of bullying, even on the elementary level, this information and curriculum is essential in 2012,” said Chapman.

Meetal agrees that there is currently very little education about the Holocaust in classrooms. She chooses to educate through her art.

“When I see someone, of any age, get emotional and affected by my art, I know I am doing what I was supposed to do,” she said. “It’s all about education so that something like this can not happen again.”

The message of “Never Again” is ubiquitous in the museum, and especially in the new exhibit. As viewers pass the wooden dolls shelved behind a sheet of glass, and the tubes of pennies climbing towards the sky, a feeling of “what if?” creeps into the art-filled rooms. The chilling glimpse into Jewish children’s semblance of normality throughout the Holocaust makes for a stirring exhibit.

“What will it take for us to say ‘enough,” Halperin said.

The exhibit is open through March 18. For more information, visit www.dallasholocaustmuseum.org.