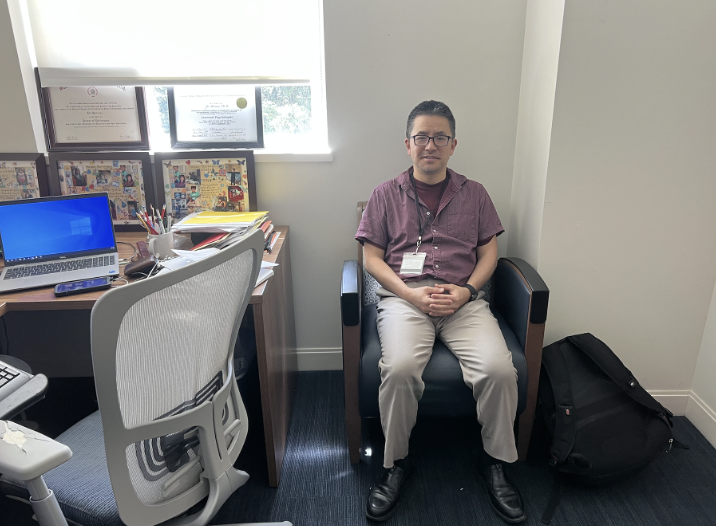

Michael Noble was the first child in the Dallas area to receive the implant. STUART PALLEY/The Daily Campus

Michael Noble was one of 1,000 children born without the ability to hear. For more than two years, Noble never heard his family call him by name. Laughter and cartoons were all common parts of his childhood, with just one exception – he could not hear any of them.

Born on Oct. 4, 1988, Noble was diagnosed profoundly deaf when he was 18 months old, a victim of the most common birth defect in infants, according to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. It would take three years until he would hear his first sound, a conversation between his parents and grandparents.

“I was way too young to really understand why I couldn’t hear. I don’t think that I realized that I could hear,” Noble said. “The idea of hearing was completely distant from me at the young age that I was.”

For years, cochlear implants were routine surgeries for adults with hearing problems, but there were no children in Dallas who had undergone the surgery. The FDA approved the surgery for children just one month before Noble went under the knife. Today, the implant, situated behind his left ear, is the reason the senior at SMU can hear his professors as he sits in classes in the Cox School of Business.

Just before this third birthday, Noble became the first child in the Dallas area to receive a cochlear implant. As word reached the Noble family that the Callier Center and the University of Texas Southwestern were teaming up to perform the surgery, the family took the plunge in hopes of giving their son his first sense of sound. The surgery cost the Noble family about $60,000, followed by intense speech and auditory therapy.

The device rests wrapped around Noble’s left ear and is barely noticeable to those directly facing him. Noble does not hear sound directly through his ear but rather through signals that are transmitted through a wire that is connected to the implant. It was tough in the beginning, but Noble had gotten used to it over time.

“When something completely new has been ‘turned on’ like hearing, it’s overwhelming,” Noble said. “Every day brought a whole new set of sounds for me during the first weeks of having the implant.”

Noble can attend school, drive a car, listen to his iPod and experience the every day sound of a cell phone and coffee shop, all because of his surgery, successful in part because of the Dallas Hearing Foundation. With an intense passion for cars, he drives a green Jeep Grand Cherokee, he hopes to maybe one day combine business and pleasure in the automotive industry.

Today, Michael, 20, a member of the university’s Honors Program, has plans of graduating a year early to pursue an MBA at either SMU or The University of Texas. Original plans of only developing the reading level of a third grader and attending a school for the Deaf are long forgotten. Today, Michael is an intern at UT Southwestern in the Department of Immunology, working as a healthcare management intern. Instead of satisfying the expectations of his peers in the deaf community, Michael has gone above and beyond expectations – living a normal life.

As of April 2008, more than 59,000 adults and children have received cochlear implants, according to the NIDCD. Many members of the deaf community, those who still rely on hearing aids or sign language frown upon the idea of deaf people relying on the device to hear.

When I take the implant off I hear absolutely nothing,” Noble said. “In fact, I get the greatest sleep because of that. I’ve just been really blessed because I wouldn’t be where I am today without the cochlear implant and the help of my speech therapist and my doctors and my parents.”

However, according to Michael, he is among the minority of members in the deaf community to receive the implant. While Michael now finds himself amongst another minority, he is nothing but grateful for this implant. He cannot communicate through sign language as most deaf people do, and has never had to use a hearing aid, or captions during a movie.

“The deaf community is actually against the use of cochlear implants because they think when you’re born deaf that’s part of who you are and you shouldn’t alter that in any way, but I see it in a completely different way,” Noble said. “If I were to try to do anything with them they would shun me. There’s two types of deaf communities now – those who are for using the cochlear implant and those who are against it.”

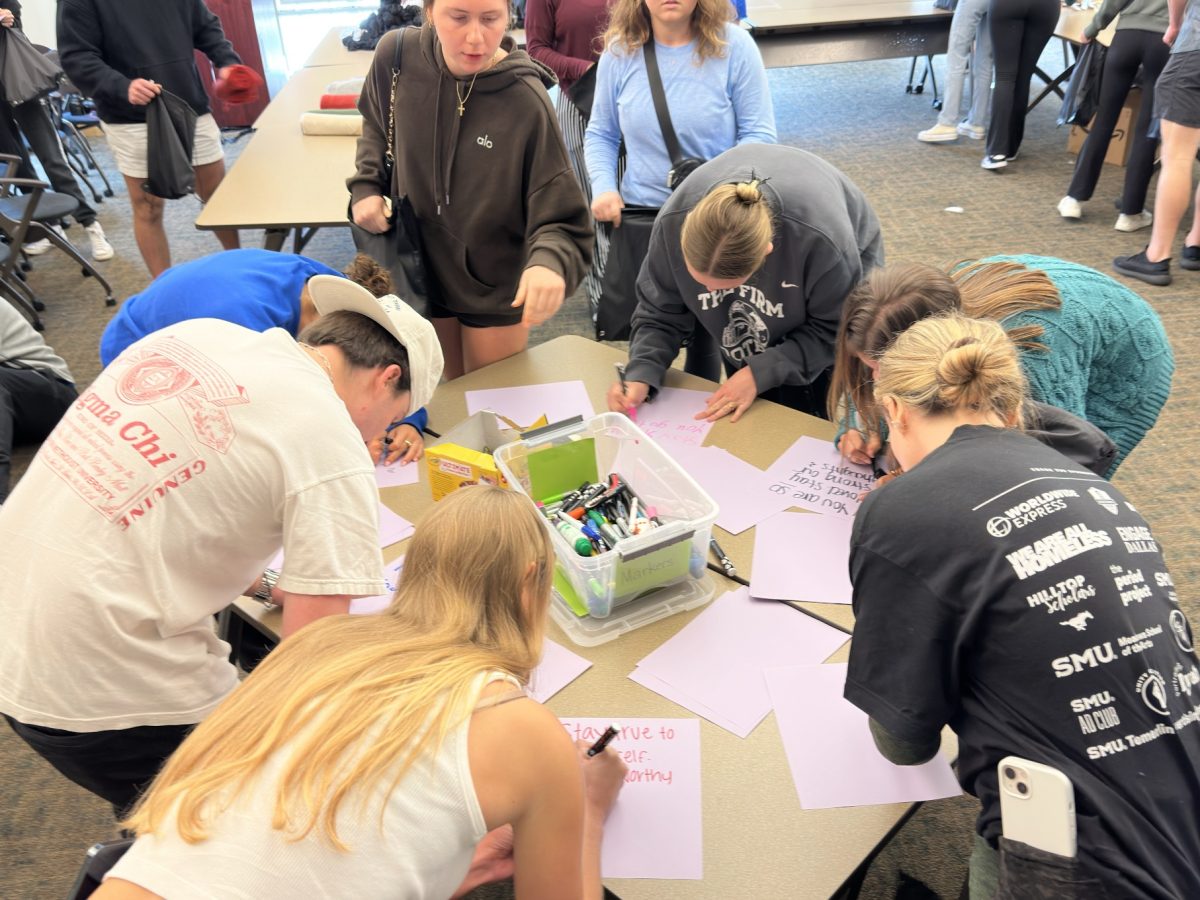

Serving as the “poster child” for cochlear implants for the DHF, the student and his co-implantee have formed a great relationship, as both are actively involved in helping work with the DHF in getting underprivileged children the implant.

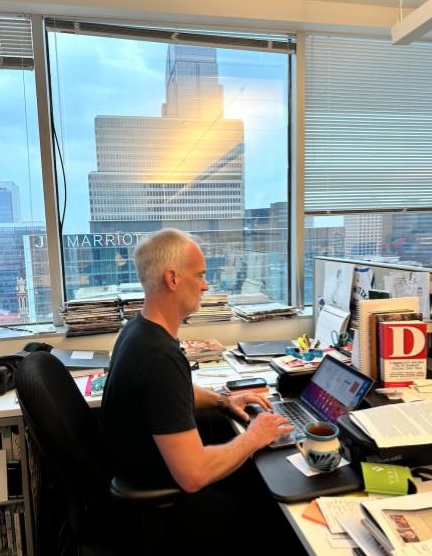

While most people ignore the device, one professor at SMU, Pauline Newton, a rhetoric teacher, knew exactly who Noble was when she spotted him studying in Fondren Library.

“It’s been great to know Michael,” said Newton of meeting the only other person at SMU to have the implant. “It’s a nice network for us at SMU, and Michael is a terrific role model for children and their parents who are considering the cochlear implant.”

Newton, also born profoundly deaf, used to scream as a child in an attempt to hear herself before she got hearing aids. It was not until she was at SMU that she upgraded from hearing aids to cochlear implants.

“When I got the implant I could actually hear more than one thing at a time,” she said. “It sounds strange, but when you’re amplifying a sound with a hearing aid, the loudest sound dominates everything else.”

“The day I got the implant activated, I came home and I turned on the water and put down the food for my dog and I realized I could hear the water and my dog chewing at the same time and I thought, ‘I didn’t think people could do this’,” Newton said.

As an undergraduate student at Hollins University – a small all women’s college in Roanoke, Va., Newton developed an intense passion for writing. Expecting herself to follow in her three brother’s footsteps of going to law school, the San Antonio native instead attended American University for her Master’s and later the University of Tulsa for her Ph.D.

It was her love for writing that brought her to SMU to become a teacher.

“People ask me, ‘How can you possibly be teaching if you can’t hear your students when you’re conducting a dialogue?’ Or, What if there’s some kid in the back of the room trying to take advantage of the fact you can’t hear them?” said Newton of people doubting her ability. “But it’s really funny because my students will say ‘shh’ to that person. It’s a great experience in having them step forward.”

Both Noble and Newton still remain active in working with the DHF. This December, the non-profit organization will host its “Sounds of the Season” Gala to raise funds for deaf children and adults. Since starting fundraising efforts in 2001, the DHF has raised over $1 million.

It’s been a great experience to really do something progressive,” Newton said of working with the DHF. “People think if you have a hearing loss you can’t do anything. You can’t work or hold a job for example. Just because you have a hearing loss doesn’t mean you’re completely deaf. There’s a lot of stigma associated with it so it’s nice to show that there are other options out there. Michael and I are that evidence, and the Dallas Hearing Foundation helps us to achieve basic skills of attending school and excelling at our jobs.”

SMU student Michael Noble pictured with his hearing implant. STUART PALLEY/The Daily Campus