I like to win just like any of the rest of us, whether it’s Saturday afternoon at Ford Stadium or in the stock market. It feels good and has definable benefits, but it’s not all it’s cracked up to be. Winning has its downside too, and defeat does not cancel meaning.

Some time ago we here at SMU confused multiple purposes of play with the singular goal of winning, thereby mistaking a relative value for an absolute one. For a time, we suffered greatly for our misapprehensions. As we regard the larger purposes of athletic competition within an academic framework (as distinct from professional sports played primarily for profit and then for gladiatorial glory), it is proper to keep in mind the limits of “binary imagination,” the idea that there are only absolute winners or total losers and that one can distinguish the two by the final score.

Binary thinking reduces life to an either/or simplicity and casts human complexities in flat-screen dimensions. Consider the indices we live by: the sweep ratings on TV, NYSE and NASDAQ, the GRE, MCAT and the ubiquitous SAT.

It was Jim Schutze, years ago when Dallas still had two daily newspapers, who likened professional, para-professional and semi-professional sports to “the cultural and municipal equivalent of a tractor pull.” So far, our SMU Mustangs have escaped the application of that analogy, but we know it was not always so.

Similarly it is important not to fall prey to what left-of-center guru Norman Lear calls “Triumphant Lombardy-ism,” the philosophy of the now-deceased football coaching icon who proclaimed, “Winning isn’t the most important thing; it’s the only thing.” Of all publics around, we in the academy know the fallacy of that limited vision. I know of no one among us today who would lay claim to tenets that assert, “If I’m not an absolute winner, I’m a total loser.” There emerges in this short-term, bottom-line climate the paralyzing fear that doing one’s best is an insufficient outcome. It is accompanied by its necessary corollary: Winning alone is the only norm for successful performance.

Of all the institutions of higher education around today in NCAA Division I-A athletics, surely we at SMU understand the fallacy of that perspective. We enjoy winning, to be certain. Sometimes victories remain elusive. I have great confidence that we will win football games in the future and perhaps, just perhaps, at the end of some season, accept an invitation to a bowl. Given the number of bowls out there, the odds will shift at some point in our favor. But in the meantime, we are well-counseled to keep our balance.

Sports are not the locus of the moral lapses in our day. Our social malaise is much deeper than the Astroturf on the practice field, far broader than the span of end zone goalposts. It’s important to remember that it’s not winning or losing that really builds character, but how we play the game. Sounds trite, doesn’t it? However, sometimes truth is like that.

Consider this story: We were a proud basketball team at Garden District Academy in New Orleans back in 1960. We were young, inexperienced, unskilled, but we loved the game. For two years we played only teams that bested us. We lost EVERY game! On weekends we’d have “came close” parties instead of victory dances. Our first win was a forfeit in 1963. The visiting team forgot the game!

In our third season we fought to our first real victory – two points in double overtime! -but not before one fateful Tuesday night at St. Mark’s gym on North Rampart. Those kids must have played basketball in their cribs. Save for the five foul shots we made, they would have skunked us instead of simply beating us to pulp. As it turned out, we lost 106 to five. Needless to say, we all survived, graduated and endured the temporary pain of that dark night. From this vantage point, I cannot say that such an experience was as enjoyable as a ton of victories might have been. But it may have been just as useful.

Binary imagination is alive and well today, and it must be identified and named. Some time ago one of the “winningest” coaches in college football was annually hung in effigy by otherwise proud supporters. He posted consistent winning seasons and bowl-game victories like clockwork but had occasional difficulty besting his archrival, Bear Bryant’s Crimson Tide. Forced out at LSU, he became commissioner of the Southeast Conference. That’s binary imagination with an ironic twist.

In the face of any human-generated absolute, other values collapse under the disproportionate weight of a win-dominated value system. Sometimes recognizing and then naming the fuzzy, indistinct shapes at the edges of those disproportions requires sheer courage. Clear-headed decision-making in such environments requires uncommon levels of calm discernment. Einstein correctly noted that velocity distorts perception and bends reality itself. Bend an ear to the rest of my story.

A few years ago, a dear colleague and I led a work camp at the St. Mark’s retreat center near New Orleans. One afternoon we traveled across Lake Pontchartrain and stopped at St. Mark’s Community Center. For the others it was an interesting stop before supper. For me it was a pilgrim’s return to a poignant personal shrine, a moment that mediated meaning – meaning in an event long since passed but strangely present. The tart taste of defeat was fresh as last evening, but there was also joy. In that gym that afternoon I felt once again the excitement of playing, and perhaps more important, the certainty and anticipation of yet another game.

In that moment I recognized something I had long forgotten: the possibility, yes, just the possibility that defeat can become a sacrament, redemptive in and of itself, an authentic means of grace that brings new understanding, new meaning, new configurations to life.

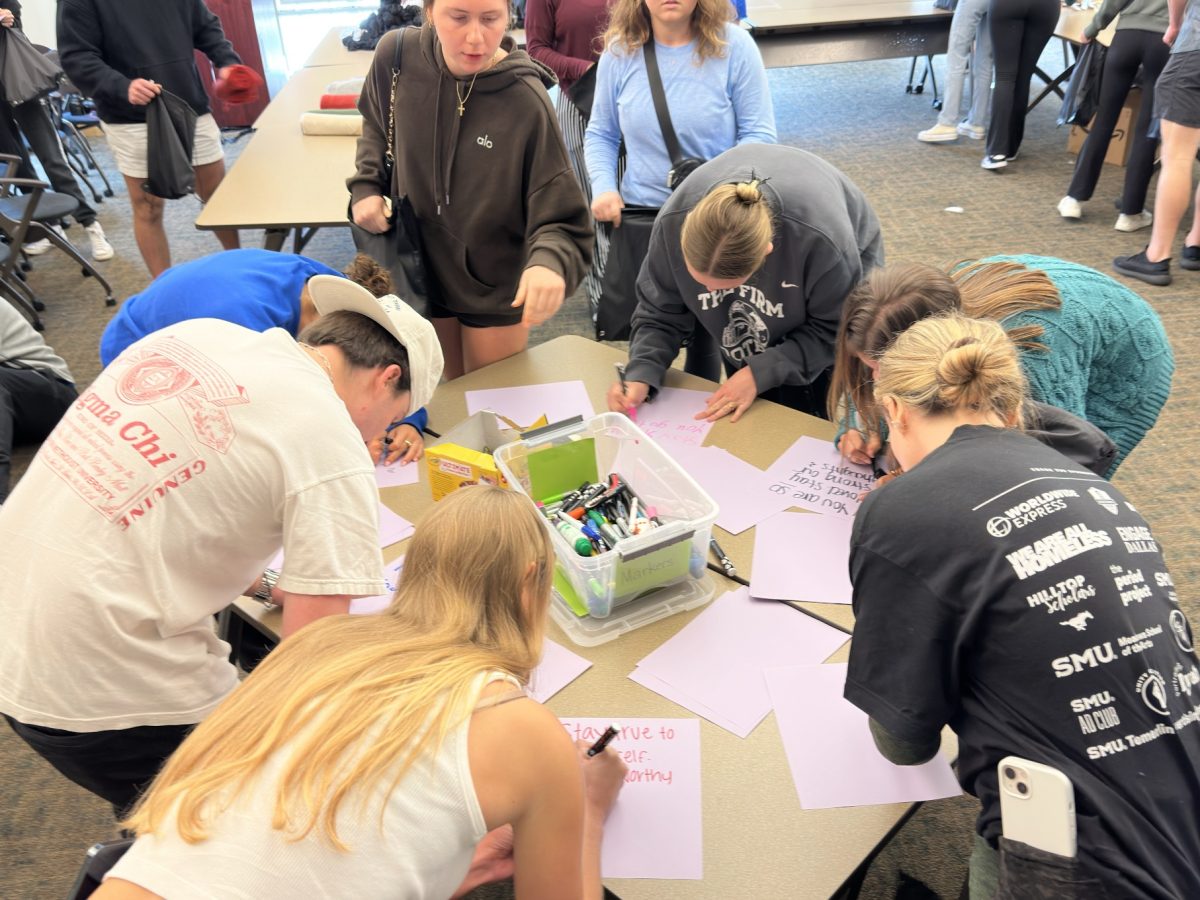

Maybe as an academy of higher learning ours is not the vocation solely of winning, on whatever the playing field, but that of being faithful to our callings as teachers and learners, researchers and scholars, and as coaches. In our own way we are each crafters of young spirits who, I trust, will at some point come to understand the importance of balance and, yes, both the value of winning and the potentially redemptive power of defeat.

Pony up!

About the author:

William M. Finnin, Jr., Th. D. is the Chaplain and Minister to the university