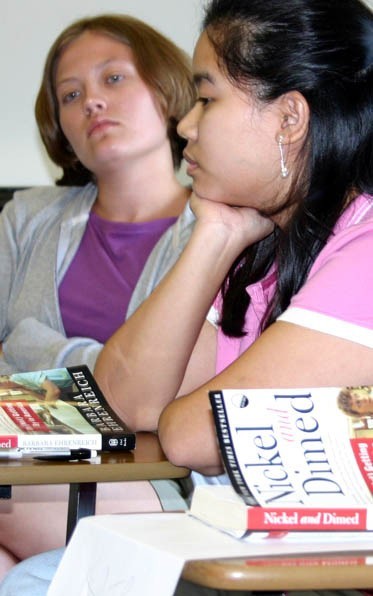

Freshmen common reading puts face on hard statistics (Photo by Ben Briscoe, The Daily Campus)

Within the first day of picking up Barbara Ehrenreich’s “Nickel and Dimed,” this year’s freshmen common reading, I did not think I would have a strong reaction to it. However, just days later I began to be disturbed. In the 221 pages of the non-fiction work, Ehrenreich, the author of 12 other books and an essayist for “Harper’s Magazine,” takes a hard-hitting look into the lives of the working-class poor in order to determine if it is possible for a family to live on minimum wage.

What disturbed me about the book is not that it was the first presentation of the problem that I had encountered. I have long known of the statistics that support Ehrenreich’s main argument that wages are simply too low and rent is too high, but the author puts a human face to the numbers. She allows one to easily connect with the problem by leaving her middle-class life behind and diving headfirst into the lower-class culture. It was the story of the individual that raised such emotions in me.

Through her trials and tribulations as a waitress, maid and Wal-Mart employee, Ehrenreich discerns that the only way to make it in the world of minimum wage is to work two jobs. Even then it is often hard for her to scrape by.

But Ehrenreich does not just draw on her own personal experiences; she also tries to convey the standards of living of her co-workers as well. She tells stories of her hard-working friends who have to live in their cars because there simply is no affordable rent to be found.

While some critics of the novel, such as Laura Miller of Salon.com, have argued that Ehrenreich only uses the text to advance her agenda, it was clear to me that the only agenda she held was to simply report what she experienced exactly how she experienced it. While their was undoubtedly some bias that a lifetime of preconceptions can bring, I feel it was minimal.

While the topic may seem dull, “Nickel and Dimed” is full of sarcastic wit and entertaining insight into a culture that is a far cry from that of many in the SMU community.

The one major drawback to this book is that Ehrenreich never presents a clear, or even subtle, solution to what she calls the “state of emergency” that is the large population of working-class poor. While this was a disappointment to me, it should be noted that in an interview with commonwealthclub.org Ehrenreich claimed, “I am not sure what the solution to this crisis is, but I knew I could contribute to the remedy by simply portraying the problem to people smarter than me in the position to fix.”

“Nickel and Dimed” is a quick read that will challenge you emotional and mentally as Ehrenreich presents a culture that turns out to be foreign to her target audience—the middle class.