London Calling (Photo by Marissa Lofflad)

Awakening to mayhem

At the time, the obnoxious guy on the bus didn’t seem that important.

It was 2:30 in the early hours of July 7 in the Piccadilly area of London. Several of us had been out clubbing. The city was in a magical mood.

A few days before, the Live 8 concert—a benefit to focus the world’s attention on African poverty—was held in Hyde Park. Twelve hours earlier, London had been awarded the 2012 Olympics. Now it was time for us, a group of SMU co-eds, to get to our dorm.

As we approached the bus stop, a balding, Middle Eastern man in his early 40s confronted one of the girls with us, making crude sexual remarks. We were relieved when our bus arrived; we figured we’d seen the last of him. We were wrong.

He followed us on to the bus and began screaming in a British accent, “Shut up. You have two choices: Get off the bus or you’ll be sorry.” We were cornered. Luckily, the bus driver heard the commotion and ordered him off the bus. As he left, the man turned toward us and said, “Just wait for tomorrow, you stupid Americans. You are going to suffer the consequences. I will see you on the bus tomorrow.”

We reported the incident to a guard at Regents College, where we were staying as part of a group of 50 SMU students on a five-week, study-abroad program. The guard nodded, and we went to our rooms.

Shortly after 9 a.m. that same day, most of us boarded a train at Euston Station and departed for Ireland. We were sleepy but excited. Then word began to circulate that three bombs had exploded in the Tube, London’s enormous subway system.

Junior Perrin White recalls waking and hearing: “Bombs in London! Bombs in London!”

“I kept running these words through my mind unable to process it as reality,” she wrote in her journal that same day. “Slowly, more students awoke as the word spread. Soon the whole train was alive with cell phones ringing, people discussing what they knew, but above all, a feeling of utter shock.”

The news kept coming in rapid, confused bursts. We had no television or radio or access to the Internet. Much of our information came from worried parents who were calling from the United States, where it was early morning.

We discovered that in a time of crisis, priorities change quickly. Anne Lowery, a junior, believes her life changed in five minutes.

“I got on board the train to Dublin worrying about my homework, my lunch and my clothes,” she wrote in her journal. “Now I sit on board worrying about my life.”

As the train raced through northwest England, new information came in: A fourth bomb had exploded on a red, double-decker bus just 200 yards from the station where we’d left. The close proximity of the attack was frightening for Annalise Ghiz.

“Chills ran down my spine when the news sunk in,” said Ghiz, a junior majoring in journalism. “The bus bomb was right outside our station. We barely escaped a ticking bomb.”

Barbara Kunzinger, a junior majoring in advertising, said the remainder of the journey was the most emotional one of her life.

“The rest of the train ride was a combination of fear, crying and silence,” she wrote in her journal that day. “I am a pretty fearless person, but this had me freaked.”

Before the attack, no suicide bomber had struck the United Kingdom. That all changed on the morning of Thursday, July 7. A photograph published in each of London’s 10 newspapers showed four men entering the Luton railway station, their backpacks filled with homemade explosives.

First-hand views of devastation

Three bombs exploded in the Tube. A fourth bomb blew the top off a bus. The explosions killed at least 52 persons and injured more than 700, according to published reports.

The worst carnage occurred at King’s Cross, a Tube station in the center of London. The Rev. Nicholas Wheeler, a clergyman at St. Pancras Church, arrived at King’s Cross moments after the bomb went off. “It was a chilling scene,” said Wheeler, a tall, intense man with blue eyes peering out of black wire-rimmed glasses. “There was a woman who made it out of the rubble but died of wounds shortly after. They laid her out on Platform One.” Wheeler spent the rest of the day tending to the injured and the dying.

That afternoon junior Meghan Beattie was scheduled to fly from London to Ireland to meet the SMU group. The bombings changed her plans.

“The day of the bombings the streets had hundreds of people walking in total silence,” she recalled. “I saw businessmen and waiters and an old woman with heavy bags all walking side by side without any other options for transportation. The stores were closed. It was a long day of death, loneliness, police and loss in a big city.”

The bombings changed many plans. After arriving in Dublin, most SMU students went to a pub to unwind. But a half-dozen students spent their first two hours in a police station talking to six detectives about their encounter with the obnoxious guy on the bus.

By the next day it appeared that life in London was back to normal. “On July 8 people still seemed hesitant and scared, but it was like they had moved on,” Beattie said. “Buses were crowded, stores were open and packed with shoppers.”

For Courtney Birck, a SMU senior headed back to London by train, it would never be the same.

“I am so scared to go back to London, and I don’t think that I will be able to ride the Tubes at least for a week,” Birck wrote in her journal three days after the bombings. “I cannot stop my leg from shaking, and I really don’t know what to do or what to think. I am just so scared. We have all seen terrorist attacks on TV, but I have never been so directly affected by something like this.”

Refusing to fear terrorists

After July 7, London was a different city as evidenced by the makeshift memorials at the four bombing sites.

The bombing at King’s Cross killed 21 persons, more than anywhere else. Faces of the missing are plastered on the walls. An impromptu memorial has been erected just outside the Tube stop. Visitors from many countries come by to pay their respects, leaving behind candles, brightly-colored flowers, posters, cards and notes. One read:

“Do not despair. We will pick up the pieces and Carry On. Our Determination is greater than theirs.”

Suicide bombers do more than kill and maim. They want to destroy the fabric of a city. “Suicide bombers are silent predators,” said Margaret Stokes, a senior majoring in journalism. “You never know when they are going to attack.”

Entering the Tube used to be routine. Last year, more than 40 million persons passed through the gates at King’s Cross alone. Now it is a perilous decision.

Karim Boularis, a security guard, has always used the Tube during his 17 years in London. But not lately. “I’m too scared and nervous now,” said Boularis, 42, a slender man with a long, salt-and-pepper beard. “You never know what can happen.”

Ariana Farris, a senior majoring in broadcast journalism, would not take the Tube or a bus. “I take taxis everywhere,” she said. “I am afraid of the Tube. And I can’t get on a bus.”

Others are determined to continue their lifestyle. Michelle Hewett, who has lived in London all her life, was back on the Tube a few days after the bombings. “You have to get on with your life,” she said.

The bomb

ers struck the Tube and a bus on July 7. Two weeks later, a new group tried to do the same thing.

A second attack

On July 21, four explosions occurred—three on the Tube and one on a bus. Only one person was injured because the detonator caps—and not the bombs—exploded. Police said the intent was to kill. They said suicide bombers again were responsible.

The first explosion took place near Shepard’s Bush station on a southbound train at 12:20 p.m. A man wearing a dark blue baseball cap then leapt out a window, ran up the tracks and cut over, passing the headquarters of the British Broadcasting Corporation. A few minutes earlier, more than 30 SMU students had left the BBC headquarters and crossed the street. “Once again, we missed a bomber by minutes,” said Raul Magdaleno, a senior.

Initially, all four bombers escaped.

For many, the bombings had gotten out of hand. In Saturday’s edition of The Independent, the headline on the lead story read: “City of Fear.” That same day, police found an unexploded bomb in a London park.

The city editor of the Evening Standard wrote a column saying Londoners had lost all sense of certainty. “There is a Web Site set up for people to say they’re not afraid,” he wrote. “But we are afraid.”

Mayor Ken Livingstone told Londoners not to allow the terrorists to change the way they live. A writer for The Guardian said that is impossible. “Who in London hasn’t changed the way they live, or had it changed for them?” he wrote.

More police patrol Tube stations. More soldiers with automatic weapons guard high-risk areas. More London police walk the streets wearing bulky, bullet-proof vests. And everyone pays more attention to their fellow passengers on the Tube and the bus. “Everyone is a suspect,” said Perrin White.

Fear can produce scapegoats. Many Muslims in London say they routinely are treated with suspicion. Boularis, the security guard, said buses often fail to pick him up because he is Muslim. Others say they are simply being prudent, noting that police said the first group of suicide bombers was Muslim. “Yesterday we were getting on the Tube and a Muslim-looking man was wearing a big backpack like the bombers wore,” said Lisa Nesuda, a 22-year-old senior. “My group moved away from him and others followed. I feel bad about stereotyping people. It is not something I have ever done before.”

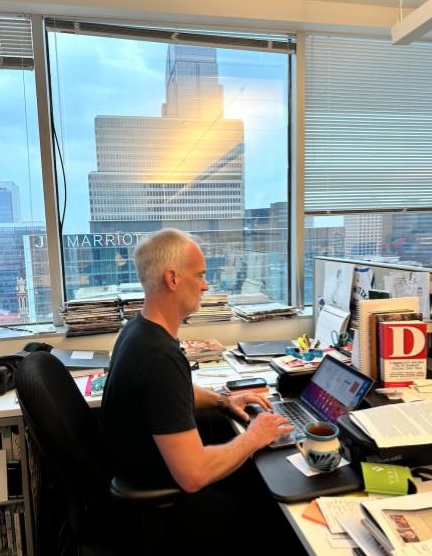

So far, matters have not gotten out of hand. But Michael White, the veteran political editor of The Guardian, says they could. “I would have half-expected white neo-Nazis to have bombed a mosque by now,” he said.

Of course, everything is relative. Suicide bombers struck London twice in two weeks, killing 52 persons. Over 10 recent days in Iraq, 31 suicide bombers killed 238 people. During World War II, the German Luftwafte bombed London and other English cities for months, killing more than 43,000 Brits.

Coming to terms with terror

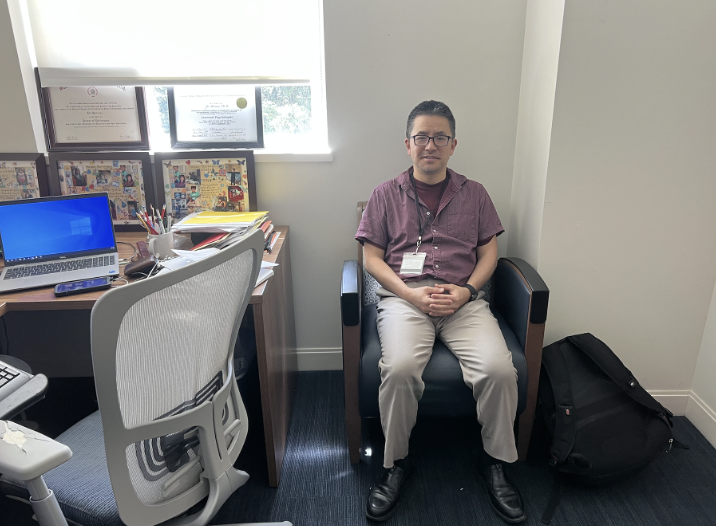

Most Americans have no experience coping with suicide bombers. Now, imagine if you had children to look after. Or 50 SMU students, as did Nina Flournoy, director of SMU’s London program for the past five years. “I look at it as a learning experience,” she said. “We’ve all shared something significant. I can’t predict how it will impact the future of the program, but I can promise we will never forget the summer of 2005.”

Anne Lowery, a junior from Houston majoring in advertising, said the learning experience has not been easy. “This trip,” she wrote in her journal, “has been a loss of innocence.”

Yet most SMU students said they did not regret coming to London. They said the bombings taught them a paradoxical lesson: Terrorism can strike anywhere, but we cannot let fear rule our lives. As Kate Meyer, a junior majoring in corporate communication, wrote on July 7: “I will ride the Tube once again, and I will continue—along with everyone else—to live my life. Living in fear is what the terrorists want, and I will not allow them to have control over me.”

This story was written by the members of Craig Flournoy’s 2005 London Study Abroad journalism class.