Entrances made accessible to students after the first threats were limited and included only the student entrance and the front entrance. (Natalie Yezbick)

As Highland Park High School continues to be plagued by disturbing threats from an anonymous source or sources, it is the students who say they are bearing the brunt of the situation. From reports of long lines to exit the parking garage during a bomb threat, to bullets left in bathrooms, to rumors about who is behind the alarming text messages and notes, Highland Park High School students are sounding off.

The school has heightened University Park Police presence at the school and has brought in the FBI since the first threatening note was found in January. Subsequent notes have been left on the school’s campus and cell phone text messages have been sent to students. HPISD’s Communications Director Helen Williams was not able to comment on the details of the investigation.

The most recent incident occurred on March 27 when a student found two bullets in her book bag. Later that day, it was discovered that the bullets came from the student’s home, according to Williams. HPISD is considering this an “isolated incident” and is working with the student and her parents, she said.

According to an official timeline from HPISD, students began receiving threatening cell phone text messages starting on March 7. After a long gap in communication, more text messages were sent between March 19 and 21.

Highland Park High School junior Liam Fegan knew students who had received text messages and described them as “explicit.” The texts contained offensive language, and Fegan said the messages stated that a bomber was going to “blow up the school.”

“Students will randomly in class say that they got a threatening text message,” said Trevor Drew, a senior and Highlander String Orchestra member.

Senior Lilly Kopita, who will attend the University of Tulsa in the fall, had classmates who received text messages. Kopita said the texts were “threatening that something’s gonna happen, someone’s gonna die, someone’s gonna pay.”

Williams could not comment on the content of the messages and could not give any details on what was being done to trace them. She could also not comment on whether investigators believe the threats are coming from a single individual or more than one person.

Police have conducted searches of students’ cell phones, reading their text messages for possible leads. According to a safety update posted online from HPISD, the district said they are only conducting searches of students’ phones when they have “reasonable suspicion of prohibited conduct.” HPISD said it is “telling students beforehand that certain locations, such as lockers or vehicles parked on school grounds, are subject to random search.”

Security Updates

Bullets found on Feb. 27 prompted heightened security measures, which included increased police presence at the school.

“What used to be a very free, nice, calm environment is now very tense,” said Kopita.

Initially, sophomore Gaby Gear was grateful to get a small reprieve from busy school days due to early release times, but now regrets that, saying, “We have our privileges taken away.”

Students face stricter rules concerning when they can leave the classroom. They cannot leave to go to the restroom during the class period without a faculty escort. Students believed this protocol would be lifted on March 25, but that has not yet happened.

“Police, administrators, volunteers, asking us where we’re going, what we’re doing,” said Kopita. “No one can go to the bathroom because no one wants to have to do that.”

Kopita has experienced first-hand the inconveniences these new rules place on students. During her lunch period, she went to the cafeteria to get a snack and then to the library to prepare for upcoming tests. “I got stopped by four people asking me where I was going, what I was doing, and why I’m not in class… You feel like you’ve done something wrong even though it’s not your fault.”

According to Williams, the multipurpose athletic facility is the school’s evacuation site. Students were told that they would gather in this facility with their teachers while police sweep the school instead of being told to leave like on Jan. 17.

“Now that all of the students know [the meeting place], the student can just put the bomb in there,” said Trevor Drew.

An evacuation drill was scheduled for Friday, March 22, but it was canceled for reasons not disclosed to the students. Williams could not comment on why.

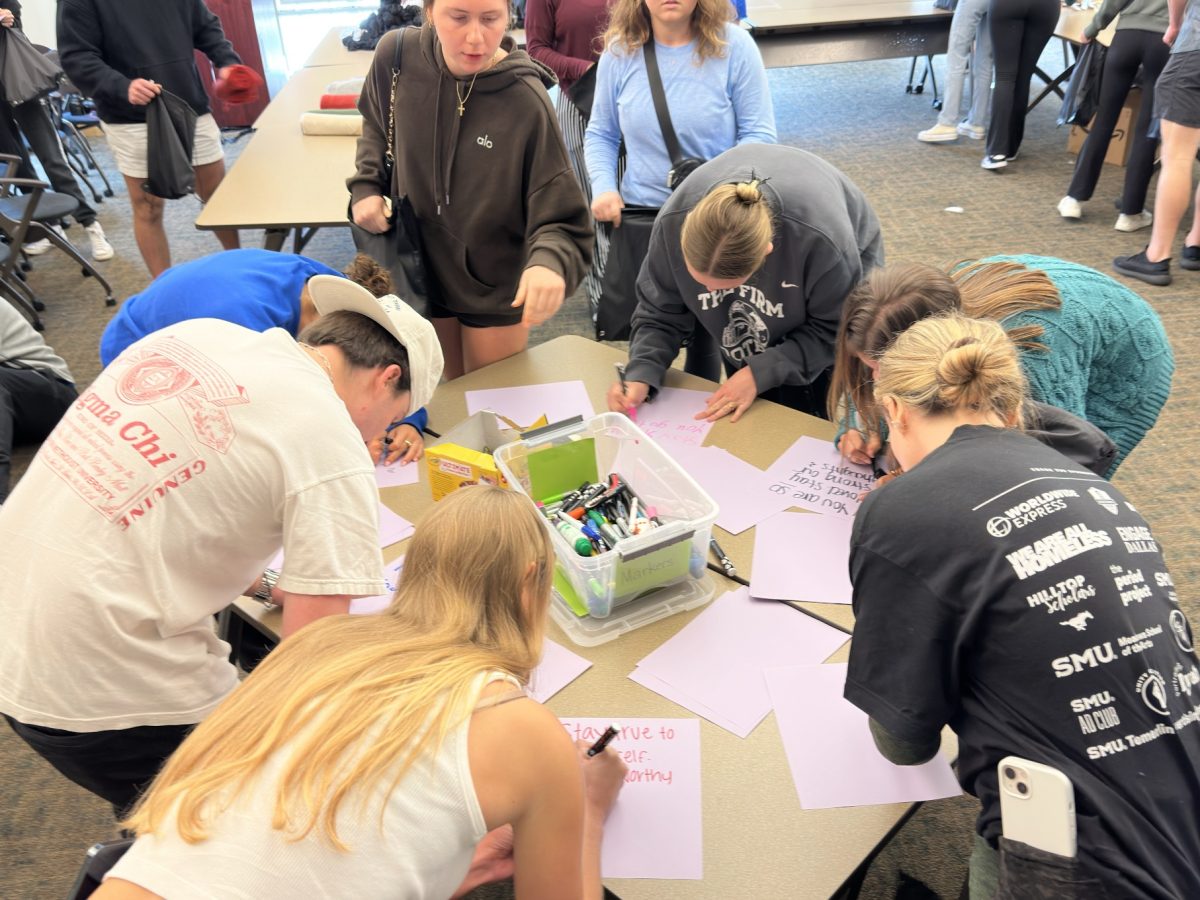

Lunch Room Rumors

Each student has his or her own idea of who is behind the threats.

“That was all everyone talked about before spring break,” said sophomore student council member Abby Loncar.

Fegan thinks most students believe the suspect is a freshman. He has heard of some teachers agreeing that only a freshman would take something like this so far.

“In my mind, I think it’s a total hoax. No student is smart enough [to do this]… or stupid enough,” he said.

Drew agrees. “I personally think it’s someone who is really wanting attention, and I think it’s a cry for help.”

“They don’t care about authority at all… if the FBI can’t figure it out, this kid is a genius,” said Loncar.

Affects on Academics

Due to all of the missed classes, teachers attempted to squeeze days of teaching into the class periods before the vacation.

“The week before spring break was actually hell,” said Loncar.

“It’s really hurt me,” said Fegan, citing the upcoming AP testing as a huge stressor.

“Students want the person to be caught. Students are behind,” said Kopita.

A Threat Timeline

The first physical bomb threat note was found on Jan. 16 in a boy’s bathroom at the school, but administration decided to keep classes in session. The following day another note was found, and students were dismissed an hour early from school.

Students were told that day what Loncar described as, “basically, just like, ‘Get out,'” at the beginning of eighth period. “There were people running out of school.”

As students left the school, a vehicle pileup occurred as they exited the parking garage. The youngest drivers, mostly sophomores and freshmen, park on the upper levels. Some of them were stuck in the garage for more than 45 minutes, according to Fegan, who rode to school that day with another student who had an upper level parking spot.

Kopita was grateful for her senior parking placement.

“I was able to get out of there in 3 to 4 minutes. If you’re on the fourth floor, you are definitely going to be stuck up there for a very long time,” she said.

A third note was found the next day, but classes continued. The school was quiet until a fourth note was found on Feb. 26 when it was evacuated and students were dismissed around 11 a.m.

“All of a sudden, all of us are sitting in our chairs, the intercom goes out, ‘Sorry for the interruption, y’all need to leave,'” explained Kopita.

The following day a box of .22 caliber bullets were found in another boys’ bathroom. The school went into a lockdown for 90 minutes before releasing the students around noon.

The students “thought, ‘The person wouldn’t try this again.’ But they did,” said Kopita.

Drew was in the classroom across from the bathroom where the bullets were found. “We are all like, okay, this is actually serious.”

“I was kinda freaked out. I was texting people, ‘Goodbye, love you,'” said Loncar.

Gear echoed Loncar’s emotional response, saying, “I was freaked out during the lockdown.”

On Feb. 28, a day after the lockdown, a fifth note was found at the top of a stairwell. Williams could not release the content of the note, but Drew described it as a list of 30 to 35 students that the writer of the note said would be killed. Many of the students listed were in the same extracurricular group at school.

Panic and Parents

Loncar estimated that there were 700 absences during one of the bomb threat episodes and said students wrote “I’m scared” on the sign-out sheet as their excuse for leaving school. Kopita confirmed this number and thought there may have been even more students that left school on their own accord or because their parents pulled them out.

“I told my parents, ‘I don’t think anything bad’s gonna happen,’ because if it was, it would’ve already happened. If anyone wanted to do anything bad, they should’ve just blown up the parking garage,” said Kopita.

“Parents knew nothing would happen,” said Fegan, but this didn’t stop some from going to the school to protect their children. He remembers one assistant principle personally dismissing over 500 students as their parents waited in the cafeteria.

“A lot of people don’t believe it, [but] some parents lost it,” said Loncar.

Both Fegan and Loncar stayed in class during the bomb threats and described classes with only three to seven students in them.

Despite all of this, many students continue to support HPISD and the police’s efforts to catch the perpetrator.

“You can’t be mad at the administration,” said Kopita.

“I have a duty to my school to fill them in on anything,” said Fegan. “I think the school knows what they’re doing and how to do it.”