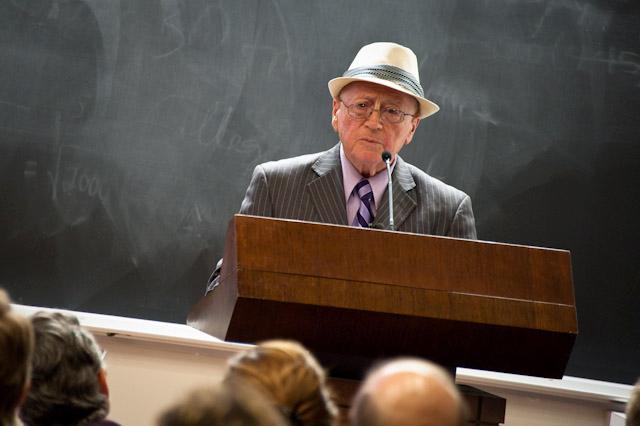

Philip Bialowitz, a survivor of the Holocaust, told his story of the rebellion in the Sobibor death camp during a lecture sponsored by the Embrey Human Rights program Thursday. (Sidney Hollingsworth/The Daily Campus)

Standing before dozens in SMU’s McCord Auditorium, Philip Bialowitz recounts the events that lead to the revolt at the Sobibór death camp.

The story of bravery takes the audience nearly 68 years into the past to a forest in eastern Poland where some 250,000 people were killed by the Nazis.

For the audience, it is a glimpse into history; for Bialowitz, it’s a continuation of the opposition against the horrors of the Holocaust.

“We did not only fight for our lives, we also fought for a better tomorrow,” Bialowitz said.

Bialowitz spoke on the SMU campus Thursday evening discussing his experience at the Sobibór death camp.

His lecture “An Evening with Philip Bialowtz” was sponsored by the Embry Human Right Program as part of the program’s effort to preserve the memory of the Holocaust.

Sobibór was one of three death camps designed by the Nazi to eliminate the trace of the Jewish people.

Of the approximately 600 prisoners at Sobibór, on Oct. 14, 1943, 48 people successfully escaped.

Eight are alive today.

“Its too easy to say he was lucky, the hand of god was upon him,” Rick Halperin, Embrey Program Director, said on Bialowitz survival.

According to Bialowitz, a majority of the prisoners brought to Sobibór were murdered on arrival via gas chambers.

At the age of 17, Bialowtiz was brought to the camp with members of his family. He said when they arrived his brother lied to the guards saying that he was a pharmacist and that Bialoiwtz was his assistant.

Needing skilled labor, the guards kept his brother and him alive while their two sisters and niece were gassed.

When new arrivals would come to Sobibór, Bialowitz was tasked with carrying their luggage and then sorting through it for valuables that could be used by the Nazis.

Meanwhile, the prisoners designated for death were left under the impression they had been relocated and they would be able to write to their families about their new living conditions.

However, they were told they would first need to have their hair cut and then take a shower.

Bialowitz, who was also tasked with cutting hair, said the prisoners were not familiar with what was going to happen to them and were often optimistic.

The women would ask him that their hair not be cut too short.

“I am convinced they did not fully realize the terrible truth until the first breath of poison gas,” Bialowitz said.

Over time, talk of open rebellion started to circulate amongst the workers.

When a number of Jewish Soviet Union soldiers were brought to the camp, the rebellion became a reality.

Utilizing their new companions’ military experience, the prisoners developed a plan that would eliminate the camp’s officials, making it easier to escape into the surrounding forest.

Bialowitz and other young prisoners drew “key Germans” away from the rest of the guards under the pretense of having found valuables during a recent sorting.

When the officials came to look at the findings they were met by the Soviet Jews armed with knives and axes.

Bialowitz remembers that when he saw the dead officers he was pleased.

“I said to myself this is for my sister[s] my niece and the thousands of others who perished in the gas chamber.

While many of the prisoners were killed in the rebellion, both Bialowitz and his brother successfully escaped.

Before the escape, Bialowitz said the leaders of the rebellion commanded the prisoners that if they survived the would “tell the world what happened here.”

Bialowitz, who came to New York after the end of World War II, spent the last 20 years telling people about his time at Sobibór.

For those who have listened, it is evident the Holocaust will not be forgotten.

“I think with his story it makes it very clear it needs to be remembered,” Lauren Zielinski, a human rights graduate student, said.