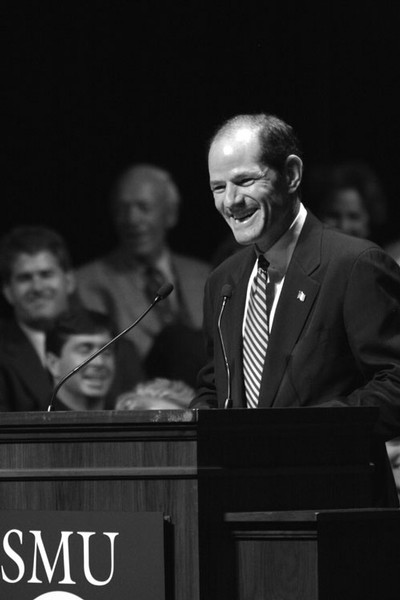

Eliot Spitzer visits Hilltop (Photo by John Schreiber, The Daily Campus)

New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer spoke at the Turner Construction Student Forum on issues ranging from his political future to federalism and the Constitution.

The first question asked was if Spitzer had any ambition to be president one day.

“I’m not running for president, I’m running for governor of New York – but thanks for the implicit praise,” Spitzer told the questioner.

Spitzer said his job as attorney general has brought him “no greater joy” than representing the people’s interests. He was elected to the office in 1999.

During his time in office, he has exposed conflicts of interest in Wall Street investment banks and cracked down on illegal trading practices.

“When you defend the integrity of the markets, you create growth,” Spitzer said. “Good enforcement is pro market and pro growth.”

Spitzer addressed a growing problem in financial markets – the unregulated growth and potential abuse of hedge funds. Spitzer said his office has been prosecuting more cases involving hedge funds, but it’s because of the market manipulation that occurs with the fund that makes the actions illegal – not the structure of the fund itself.

Another area Spitzer is focused on is Internet regulatory law. Spitzer said current laws pose problems, because it is nearly impossible to have any enforcement online. He mentioned cases where they could not reach overseas operators who were violating state law.

However, Spitzer said most of his time and his office’s time is spent representing the state of New York in more mundane cases. He said the state typically has 30,000 cases pending against it at any given time.

Spitzer spent a good amount of time on federalism and the constant battle between the state and federal governments on certain legislation.

He specifically mentioned cases when his office was trying to bring charges against firms who had ripped off investors. He said that while his office was attempting to prosecute, members of Congress in Washington were trying to push legislation to protect the firms.

“They were hazardous to the integrity of the process,” Spitzer said.

He then decided to go public and galvanize support for what his office was doing.

“The public responded by asking their congressmen why they were defending people who took advantage of them,” Spitzer said. He won, and the legislators dropped the bill.

When asked about the effects of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, the legislation passed as a reaction to the corporate scandals of the time, Spitzer said the bill’s results are mixed.

“Any law that passes Congress unanimously is inherently flawed,”Spitzer said.

He said there are good parts that require better financial reporting and accounting practices, but there have been imposed regulatory costs that have prevented some smaller businesses from going public.

Spitzer thinks state governments have backed away from giving businesses all types of incentives to relocate.

“For many years there was a descent to the lowest common denominator in terms of incentives, but I’ve noticed a move in the other direction recently. The scandals have made states smarter,” Spitzer said.

Spitzer currently lives in Manhattan with his wife, Silda, and their three children.