It’s every collegiate athletic director’s dream – national titles in football and men’s basketball in the same academic year.

Indeed, it’s a pretty far-fetched fantasy because it happened only once in NCAA history at the University of Florida in 2007. That year, the football team won its first national title since 1996 and the men’s basketball team repeated as national champions.

The titles not only ensured the university more television time and sexier facilities to entice top-notch recruits, but it also helped recruiting in a broader sense.

In the admissions season following its sweep of titles in the two big-ticket sports, the number of applications at Florida spiked 12 percent and the acceptance rate fell 6 percent. Basically, the school became higher education’s equivalent of the ugly girl who comes back to school with a new makeover-all at once she goes from being dateless to spending Spring Break in Cancún with the popular kids.

It’s no wonder the slideshow on the school’s admissions home page features a fan getting his face painted blue, presumably before a Gators football game. The slide reads “Join the Gator Nation.”

Football syndrome does not just reside in the Sunshine State. The University of Oklahoma has built a reputation as one of the finest football schools in the nation’s heartland, and students declare proud allegiance to “Sooner Nation.” At the end of the national anthem, a chorus of more than 80,000 fans complete the singer’s last line: “…And the home of the…Sooners!”

“Athletic appeal is the number one thing for some people,” said Justin Rosinski, a sophomore at Oklahoma. “People come so they can form a community around athletics and form groups. … Athletics attract a lot of people.”

For this reason, college administrators and wealthy donors pump millions each year into important athletic programs.

SMU’s donors raised Gerald J. Ford Stadium, a $62-million facility, from bare earth in 2000, and they are shouldering football head coach June Jones’ $2-million-a-year salary. Also, the university finished construction of the Crum Center, a $13-million practice facility for the men’s and women’s basketball teams, in February 2008, and is formulating plans to renovate Moody Coliseum.

It’s all part of a philosophy that Athletics Director Steve Orsini has implemented since he arrived at SMU three years ago: better sports means happier fans and more appeal for the university.

“We all know how to spell fun: w-i-n,” said Orsini, flashing a broad grin and a thumbs up.

He witnessed first-hand the impact of athletics on a college campus when he was a football captain on the University of Notre Dame’s national title team in 1977, and several months later watched the Fighting Irish’s basketball team make the Final Four.

SMU, like Notre Dame, is a mid-sized private university, and Orsini hopes SMU’s football and men’s basketball teams soon will be competing for Conference USA titles. In order to get to that point, Orsini has taken the approach of a real-estate agent.

“Athletics are the front porch to a university,” said Orsini. “You don’t have to have a nice front porch to have a good house. But if you do have a front porch, you want to make it a nice one because it gives your house street appeal.”

Empirical evidence supports athletics’ influence

Jaren C. Pope, assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics at Virginia Tech, and Devin Pope, an assistant professor at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania, studied how athletics affect admissions at 330 schools. Their findings were published in the January 2009 edition of the Southern Economics Journal.

After gathering admissions data from 1983-2002, the Pope brothers concluded that a national title in football or basketball typically results in a 7 or 8 percent increase in applicants. Making the Top 20 in football results in a 2.5 percent increase, while a Sweet 16 appearance in basketball results in a 2 percent boost.

“We found that in an increased pool of applications, there were both low and high SAT scores,” said Pope. “Schools can exploit their success by selecting more high-quality applicants from the pool.”

The study also noted that athletic success tends to provide a bigger boost at private universities. The football program at Texas Christian University, another private school in the metroplex, experienced a boost from its growing reputation in football.

The Horned Frogs burst onto the national scene in 2005 when they finished 11-1, including a stunning upset victory at No. 5-ranked Oklahoma on national television. The increased exposure likely aided a substantial jump in the number of applicants from 8,677 in 2006 to nearly 12,000 the following year.

Just three hours south on Interstate 35, the University of Texas has been in the top 20 of the NCAA Football Bowl Subdivision (formerly known as Division-IA) postseason rankings every season since 1999 and has built a formidable men’s basketball program. Since the turn of the century, applications have soared nearly 56 percent and the admissions rate has plummeted 19 percent.

Granted, the jump likely isn’t entirely due to athletic success. Many universities have seen applications rise due to a growing population of college-aged students in the middle of the decade. However, Texas’ steady growth began before the boom and TCU’s applications came back to earth in 2008 when the football team cooled off.

The drawback of big-budget athletics

For every university president who anxiously pumps a continuous stream of cash into athletics, there are more critics who argue that big-time sports hinder a university’s academic reputation.

Robert Maynard Hutchins, president at the University of Chicago from 1929-1945, is perhaps the most famous critic. He abolished all 20 of the university’s varsity athletic programs including the tradition-laden football team, which had won a national title in 1905 and enjoyed citizenship in the nationally recognizable Big Ten Conference.

When asked why he pulled the plug, Hutchins famously said, “A college racing stable makes as much sense as college football. The jockey could carry the college colors; the students could cheer; the alumni could bet; and the horse wouldn’t have to pass a history test.”

Hutchins’ sentiments are echoed by others in academia. An article published by Irvin B. Tucker III in the Atlanta Economic Journal in 1992 concluded that, while a nationally recognizable team may attract more applicants, students are less likely to graduate because they likely will spend valuable weekend study hours at the stadium.

Other critics argue that universities dramatically lower admissions standards for blue chip athletes, creating a conflict between athletic and academic missions. A study by the Atlanta Journal Constitution in December 2008 concluded that athletes at 54 of the nation’s most powerful schools score much lower on the SAT than typical students – often by several hundred points.

The school with the biggest gap between football players and students: Florida (356 points). Florida also was crowned “Biggest Party School” in the Princeton Review’s 2009 rankings of America’s colleges and universities.

Staying out of the spotlight

On the other end of the spectrum are Ivy League schools. If Florida and Oklahoma have the most welcoming “front porches” in college football, the Ivy League schools are Clint Eastwood in “Gran Torino,” pointing the barrel of a shotgun at neighbors and asking them to get off their lawn.

These elite academic schools have not competed in the FBS since 1981, when they withdrew in a dispute over television contracts. They do not offer athletic scholarships or compete in the Football Championship Subdivision (formerly Division I-AA) postseason.

Nonetheless, their admissions departments have become much more selective in the last quarter-century.

Yale University’s admissions rate was less than 9 percent in 2008, compared to nearly 20 percent in 1982. At Cornell University, another Ivy League school, applications have increased a stunning 85 percent and the acceptance rate has fallen 11 percent since 1982.

Much of the growth likely can be attributed to the growing academic clout of the Ivy League’s schools. While Florida and Oklahoma were battling for the 2009 Bowl Championship Series title, Harvard University, Princeton University and Yale were clamoring atop the U.S. News & World Report’s “Best Colleges 2009” rankings.

Building a brand

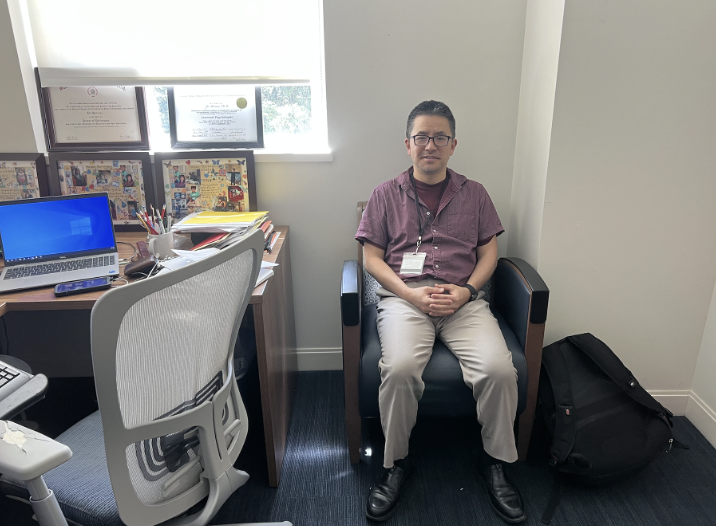

Back at SMU, Orsini can’t help but each day be reminded the importance of athletics. Floor-to-ceiling south windows in his office suite atop Gerald J. Ford Stadium overlook the football field and an east window near his desk faces Moody Coliseum.

It is not that he needs to call attention to the fact that the football and men’s basketball teams haven’t experienced much success in the last 15 years, despite numerous rebuilding efforts. But Orsini knows as well as any that some front porches are not renovated overnight.

“We’ve got to have some of the most patient fans in America,” said Orsini. “I hope we can build our brand. … I’m not talking about athletic branding; I’m talking about SMU’s branding.”

If the last several years are any indication, the university has made clear it wants its branding to involve athletics. It’s just a question of how long the renovation project will take.