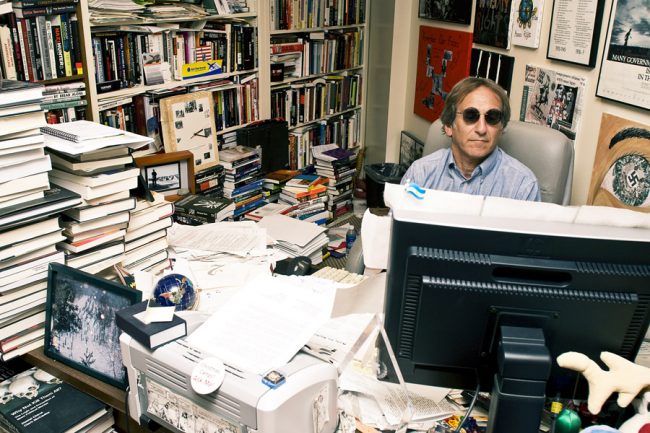

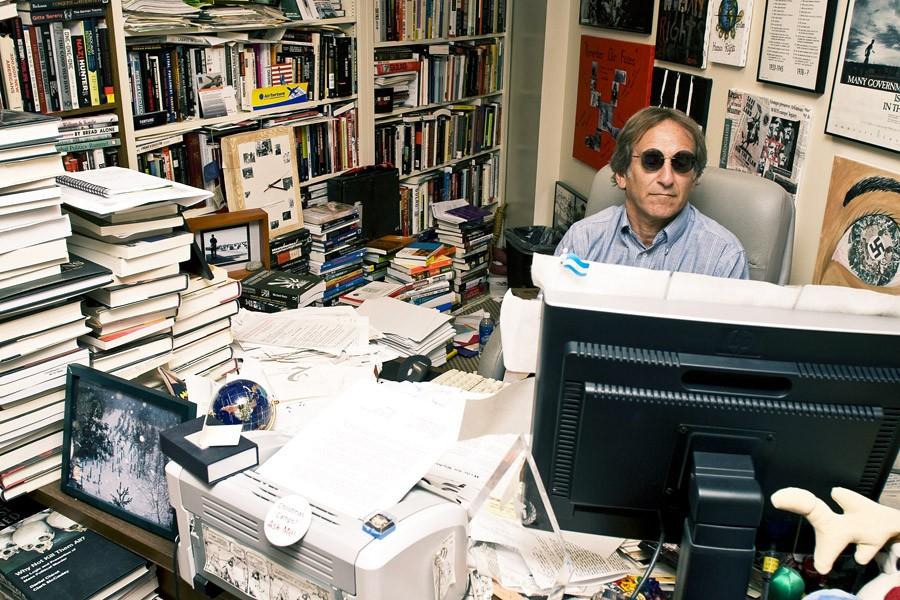

Human Rights professor Rick Halperin works in his office on Tuesday afternoon. CASEY LEE/The Daily Campus

Today, 3,297 inmates are lined up on death row, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. The third largest group of 338 is stationed in Texas. In the U.S., more than 4,500 have fallen victim to this form of punishment since 1930, according to Crime Magazine.

A 20-year-old Czech medical student, Jan Palach, set himself on fire in protest of the communist rule trying to enter his country. One SMU professor, just entering adulthood at the time, was there to see it.

Most students would not think to visit an inmate on death row, witness a lethal injection execution or travel to third world countries and see first-hand the brutality and torture humans are inflicting on others. One SMU professor accompanied an inmate’s pregnant sister to see her brother put to death.

One SMU professor goes to all lengths to ensure everyone is given the respect they deserve.

Meet Dr. Rick Halperin, a human rights educator at SMU.

On this day in history

Halperin will never celebrate another birthday. But it is not for the reason most think. He does not think it is a coincidence his birthday is marked by the cause he is most passionate about.

July 2, 1976, was a night filled with laughter and food, a time spent celebrating with friends, but Halperin does not remember the festivities of the evening. His birthday, instead, will forever be remembered as what Halperin thinks of as a national day of shame.

“When my birthday comes around every year, I just don’t celebrate it,” Halperin said. “I just can’t celebrate that day for my personal reasons when something much bigger and more important to me is at stake.”

Halperin, then 26 and a graduate student at Auburn University, only remembers the TV announcing the Supreme Court had made the death penalty legal again. There may have been a birthday cake, but the details are fuzzy. Only the static on the TV was clear. A night commemorating “America’s Bicentennial” was nothing worth celebrating to Halperin.

“The last item on the news was a small blurb saying the U.S. Supreme Court had re-legalized the death penalty in the U.S. After a four-year hiatus it was back,” Halperin said.

Halperin has relentlessly been fighting for the abolishment of the death penalty for nearly the last four decades. Growing up, his mother told him everyone was to be treated with the same degree of respect; there was no such thing as an inferior person.

“I would say the set of beliefs I grew up with that she instilled in me, the idea that all people, regardless of who they are or what they may have done, need and deserve manners, dignity, respect and understanding,” Halperin said

Today, fighting against the death penalty, Halperin says, is one of his most passionate causes.

“It’s the most important human rights issue to me – in this country or any country that has it,” he said. “I just believe it’s wrong to kill, and having witnessed an execution, it’s an un-debatable point for me.”

Halperin spends what little free time he has fighting for the lives of others. Visiting as many of the prisoners on death row as he can cram in between teaching and fighting for other causes has become routine to Halperin, who spends hours on end chatting with the prisoners during each visit.

Working as a sort of intermediary, Halperin has worked in helping inmates relay messages to their families and fighting attorneys to fight on their behalf. He has even gone so far as to make funeral arrangements.

A member of at least four separate organizations opposing the death penalty, Halperin has witnessed a lethal injection execution in Huntsville, Texas at the request of the inmate. One week after the request was extended, Halperin made the three-hour drive with the prisoner’s sister to see the man put to death.

Halperin recalls the experience to his students in a way the leaves many shocked and deeply moved. As Halperin tells the story about the indifference displayed by the executioners, some students shake their heads in disbelief; others stare transfixed at their professor – a man who stops at no lengths to put himself in these situations in hopes of establishing a sense of equality.

Now 59, Halperin spent his most recent birthday grading final exams from the two classes he taught during summer school.

“It was pretty unglamorous,” Halperin joked.

A Tom Sawyer childhood

Halperin, growing up in the South during the Civil Rights Era, explains being subjected to societal brutality at the age of seven.

“I would only say I was sensitized at an early age to deep-rooted social problems in America,” Halperin said. “I didn’t grow up ever saying ‘I don’t know what’s going on.’ I was surrounded by an angry, hateful society that was tearing into itself and it was hard to be indifferent.”

Growing up, Halperin was a witness to a “pretty terrible racially motivated act of violence.” While no further details were provided, the event caused Halperin to have an epiphany – between the morals instilled by his mother and the events unfolding in front of him – he wanted to be a teacher.

Besides teaching, Halperin is a current member of the National Death Penalty Advisory Committee, as well as the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty.

Since starting with Amnesty International USA in 1971, Halperin has been at the forefront of the organization, trying to abolish the death penalty around the world, while also fighting for women, gays and lesbians, political prisoners, journalists and other professionals under a constant form of assault by reigning governments, in hopes of raising awareness and helping these suffering groups. Before coming to SMU, Halperin was a professor at Auburn University, Ole Miss and Tulane – two state schools and two private institutions all rooted in the South.

“As a human rights educator, the South is the place to be,” Halperin explained. “This is where the bulk of the violations occur in America. This is where people’s hearts and minds are perhaps in greater need of education.”

“I’m on a sense of urgency to help”

Today, Halperin can be found comfortably crammed into a corner office on the second floor of Dallas Hall. He sits surrounded with books that stack from floor to ceiling, videos that look like they are about to collapse under their own weight and paintings, murals and other graphic illustrations by past and present students fighting for wall space.

Bringing an unparalleled history of experience and wealth of knowledge to students each year as part of his Human Rights Education Program in the university’s Dedman College curriculum, Halperin spearheads the program on the Hilltop, making SMU just one of 14 universities in the country to host a human rights program.

Students know him not only for his intense and gripping teaching style, but also for the signature sunglasses he wears rain or shine. Students captivated by his involvement in rallies and protests admire him, those who do not know him, strive to. A man of great interest, everyone who is anyone can identify who this man is.

“I would tell you in all honesty I don’t think of myself as anything more than a human rights educator,” Halperin said. “I’m just trying to help provide information to people who are going to have to deal with these issues in some capacity in their own lives.”

As part of his involvement with the SMU human rights minor, Halperin leads students on yearly excursions to Cambodia and Rwanda, numerous Holocaust sites in Europe and countries recovering from genocide in Africa, among other locations, to subject students first-hand to the terrors other people experience.

“I feel like I’m racing the clock,” Halperin said. “I’m not going to be able to do this work forever. I have a finite time; I don’t want to waste it. I want to reach as many people and students as possible so long after they’re out of my class they can help be an agent of change.”

With topics in his America’s Dilemma class ranging from Middle East struggles in women’s rights to genocide in Africa, Halperin, since coming to SMU in 1985, captivates students with stories, documentaries and personal experiences to teach about the evolution and importance of valuing a person’s basic and guaranteed rights.

Stories about being jailed and arrested on numerous occasions, fasting for days on end and receiving threats from people from all over the world just for putting himself on the frontlines for the benefit of others, are all part of Halperin’s life. Accounts of organized rallies and protests are peppered into class conversations, as he solemnly retells his past experiences.

As a student at George Washington University in 1970 (just four days after the Kent State shootings), Halperin found himself in the midst of a chaotic riot and face-to-face with a policeman releasing a canister gun against his cheekbone. Now partially blind, with no peripheral vision, depth perception or the ability to see colors, Halperin feels blessed just to be able to see.

Participating in non-violent protests is routine for Halperin. Halperin was hit by a blast of acid gas, knocking him unconscious while everyone fled the oncoming riot. The chemical coated his eyes as his vision deteriorated over the 45-minute window it took to get him to a hospital only five blocks away.

“I still see, Halperin said. “There are a lot of people much worse off than I am. I have few grounds to complain.”

Drawing on personal experience – Halperin has inspected prison conditions in Ireland and taken part in investigations to uncover unimaginable living conditions in Texas death row facilities and marching in and organizing several non-violent rallies – the former chair of the Amnesty International USA Board of Directors tells students first-hand the consequences of human brutality and torture that still goes on in our world today.

“Sadly, I think it seems to be a theme in my life is just a constant exposure to or an eyewitness to horrific acts of societal violence,” Halperin said. “I don’t go to these places thinking or wanting to see violence, but as it turned out, I frequently have been at places where violence erupted. It’s a quirk, a coincidence, and I certainly do take those experiences with words and hopefully pictures to students.”

Discrimination can be found anywhere, Halperin explained, but it is at the hands of others that something must be done to put an end to the violence and hate controlling society.

“One person can make a difference,” Halperin said. “I think it’s just imperative for young people to demand that their country be better. If you want a better society, work for it.”