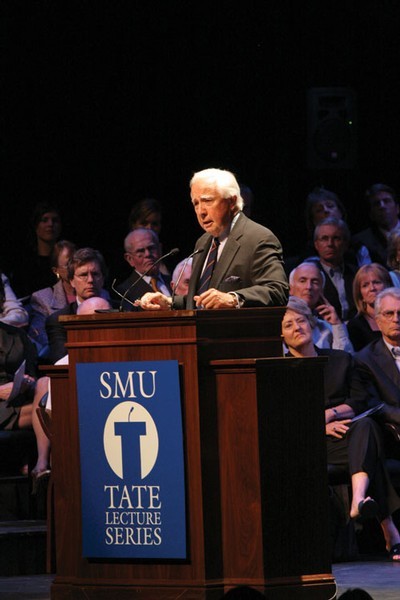

McCullough speaks at Tate Lecture (Photo by John Schreiber, The Daily Campus)

The Tate Distinguished Lecture Series hosted Pulitzer Prize-winning historian David McCullough Tuesday, as he spoke at both an afternoon student’s forum and an evening lecture.

McCullough is best known for his recent New York Times bestseller “1776,” a history of the year told through the stories of many different men who all marched with George Washington. He has written numerous books and is also the television host of Smithsonian World and The American Experience.

According to McCullough, his greatest insights into the lives of historical figures come from examining what these people loved.

“Some people ask me if I feel like I know George Washington,” McCullough said. “I feel I know him quite well because I’ve taken a broad look at what he loved – architecture, design. He never wrote an autobiography, but his creation of Mt. Vernon is in many ways his autobiography.”

Although the historian did discuss familiar historical figures, his speech was more motivational than pedantic. Particularly, he emphasized the importance of merging the teaching of the arts with the teaching of history.

“Information isn’t learning,” McCullough said. “It’s valuable, it saves time, but it isn’t learning. If it was leaning you could be educated by memorizing the ‘World Almanac.’ If you memorized the ‘World Almanac’ you wouldn’t be educated – you’d be crazy. Information is in poetry, art, music and drama. Shakespeare is as much a part of history as Napoleon. When we forget about art we’re leaving out so much that is life.”

He went on to reference the amount of information about ancient Egypt gleaned from the study of its art and the emotional connection to the Civil War that is inspired by Walt Whitman’s poetry. McCullogh claims that information is truly learned when one develops a spiritual tie with it.

“I believe you can’t really learn something unless you feel it,” McCullough said. “Just knowing something doesn’t move the spirit. You have to know with your heart. The arts are all about heart and feeling and they endure much longer than anything else we do.”

McCullough encouraged combining the teaching of these two fields, especially in elementary education where “minds are like sponges.”

“They can learn anything fast,” McCullough said. “But bringing in art makes them learn it much faster and they will learn more.”

Another dominant topic of McCullough’s speech was the state of public education in America, focusing specifically on the quality of teachers.

“We must do something about the quality of public education, and in order to improve quality we must go back to a real liberal arts education where teachers are required to major in a subject, not just in education.”

This stance was met with a flurry of applause from the audience and McCullough extended it later in the speech.

“We have to do a better job at educating our teachers,” McCullough said. “If you don’t know a subject, you’re also more dependent on textbooks. And it’s sad but an actuality that most textbooks we subject upon our children are just dreadful. It was as if they were designed to kill interest in history. It doesn’t have to be this way.”

McCullough described how his own initial interest in history and his motivation to write history books came from reading a multitude of historical novels as he was growing up.

“I loved reading historical novels, but I kept wondering, ‘What of this is true?’ And it kept nagging at me,” he said.

He aims to write history books that are as compelling as the fictional novels he was so entranced by as a child. McCullough feels there is much more to history than stale quantitative data.

“History is an anecdote to the hubris of the present,” McCullough said. “It encourages patience, fosters optimism. It is a source of strength in times of trouble.”

McCullough feels that it is not only the responsibility of schools to instill in children a passion for history, but it is also a duty of parents.

“We should be talking about history – taking our children to historical sites, art museums and great plays,” McCullough said. “History ought to be alive. It should never be boring. We should bring back discussing history at the dinner table. We should bring back the dinner table.”