By Megan Sunderland

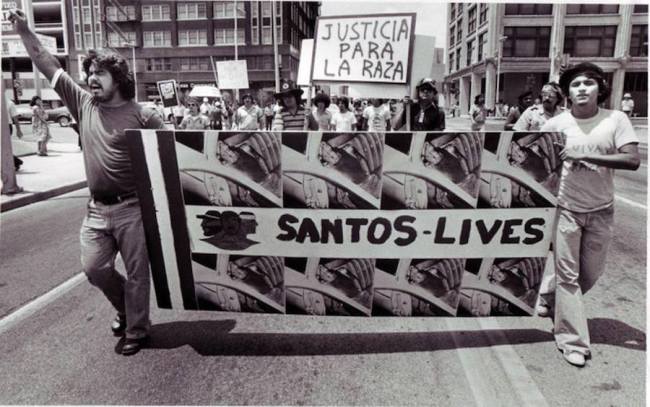

In 1973, the Senate’s hearings on Watergate began, the Supreme Court decided on Roe v. Wade, and “Schoolhouse Rock!” premiered on ABC. 1973 was also the year that 12-year-old Santos Rodriguez was fatally shot by a police officer in Dallas, an incident that is largely unknown to the citizens of the United States, even those of the city, today.

Dr. Rick Halperin, a professor and the director of the Embrey Human Rights Program at SMU, was working on his master’s degree at the university when the incident occurred on July 24, 1973.

“I was shocked at the killing of that young boy. I was certainly not shocked that the riot happened four days later, but the killing was just beyond egregious,” said Halperin.

On that morning in 1973, Rodriguez and his 13-year-old brother, David, were dragged from their home by police, handcuffed, and forced into a police car to be questioned about stealing $8 from a soda vending machine. At one point, Police Officer Darrell L. Cain placed his gun to Rodriguez’s head to coax the boy into giving information. He fired the gun once without discharging a bullet, but his second pull of the trigger released the bullet that killed Rodriguez. Through fingerprint evidence, the boys maintained their innocence.

Though Cain received a mere 5-year sentence, and only served half, Rodriguez’s death sparked the first and only race riot in Dallas’ history. As the story of the killing has begun to fade from the memories of many Dallas citizens, SMU is establishing the Santos Rodriguez Memorial Scholarship to honor and preserve the boy’s memory.

Jose Santoyo, a student involved with creating the scholarship, is in his first semester at SMU as a junior majoring in human rights. Before coming to the university, Santoyo received his associate’s degree from Navarro College in Corsicana, TX, and says that he is “considered a community activist and advocate.”

“I got involved because of the story, the Santos story, how this young boy’s life was taken away at a very young age, with him not even having the opportunity to finish school,” Santoyo said.

He explained that he feels a personal connection to the story because, for some time, Santoyo was unsure that he would be able to complete his education with his undocumented status.

Santoyo came to the United States from Michoacán, Mexico when he was 8 years old. In 2013, he was given the ability to work and obtain a social security number and driver’s license through Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a program that gives some who are undocumented the opportunity to become legally employed.

The scholarship was announced in conjunction with the unveiling of the new Latino Center for Leadership Development (LCLD) on March 14. The LCLD contributed $100,000 to the scholarship’s fundraising campaign, and allocated $20,000 “so that we can have a scholarship to go live this year,” said Santoyo. Those funds will also extend into the 2016-2017 school year.

The goal of the campaign is to secure a $300,000 endowment that will be accessible by December 2016. One student will be chosen each year to receive the $10,000 scholarship annually through their fourth year at SMU, which will be dispersed in increments of $5,000 each semester.

Each recipient of the scholarship must be studying human rights, and should be someone who “would represent, and I don’t say this lightly, but represent, with dignity, the name, the legacy, and the family of Santos Rodriguez,” said Halperin.

The Rodriguez family was not formally apologized to for the boy’s death until September 2013, when Dallas Mayor Mike Rawlings apologized on behalf of the city. According to Santoyo, Rawlings was the first public donor to the campaign, contributing $10,000.

Many are working diligently to heal the deep wounds of Rodriguez’s death that have remained open for over 40 years. However, it seems that there has been a recent rise in media coverage of police brutality around the country.

“Not young boys handcuffed in a police car, but we still have lots of shootings by police of unarmed people of color ever since then,” Halperin confirmed.

Ultimately, the scholarship will bring forth positivity from Rodriguez’s story, something echoed by Roberto Corona, the Community Outreach Coordinator for the Embrey Human Rights Program.

“I think that there is also a story of hope, you know, that we can make from something horrible in the history. We can take that as an example and make something beautiful,” said Corona.