Rolling Stone published an article in Nov. 2014 titled, “A Rape on Campus.” The story accounted a sexual assault at the University of Virginia—the assault itself and the inner turmoil of the victim. The film showed the adversity she faced in seeking recovery, notably the condescension questioning the seriousness of her experience.

The story received remarkable attention, mostly for its striking account of a gory detail that begins to shed light on the harsh reality of sexual assaults on college campuses. In the case of this article, the account was too gory. A Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism investigation donned the article “a failure of journalism.” Its study ruled the story lacked factual evidence to deem it valid. Rolling Stone retracted the article.

Yet despite the degrade in the validity of “A Rape on Campus,” the article still maintains relevancy as a recount of an issue.

More recently, fame reached a sexual assault case at Stanford University. Stanford student Brock Turner attacked an unconscious woman at a fraternity party on Jan. 18, 2015.

Outrage pooled in regard not just to the assault itself, but to the lack of sentencing that the perpetrator, Turner, received. Turner was sentenced to six months in jail, while the upper limit of his sentence could have reached fourteen years—a “measly” outcome, as the New York Daily News called it.

Vice President Joe Biden issued an open statement to the victim of the Turner case. “I am filled with furious anger,” he said, “that our culture is so broken that you were ever put in the position of defending your own worth.”

While these two cases alone account for important steps toward mending this reality on college campuses nationwide—the step towards publicity and attention to the issue at hand—the solution to sexual assault is still to come, if there even is a solution at all.

In August, Stanford University announced that it would ban hard liquor from undergraduate parties on campus. The decision follows the profile of the Turner case.

While alcohol was indeed a factor in the Stanford assault, some still weigh in on the ban with negativity.

“Even schools that are completely dry don’t get rid of the problem of excessive drinking,” said George Koob, director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Following the logic of Stanford officials, this ban means that even by eliminating hard liquor, sexual assault won’t disappear.

Stanford’s ban encompasses a means to an end, just perhaps not the right one.

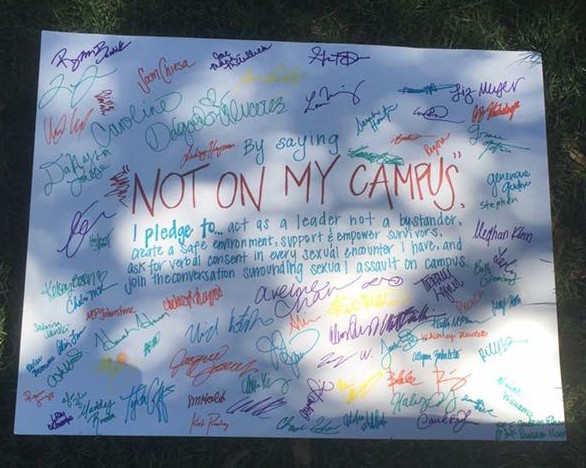

Focusing on the student voice and student-led action for an end to sexual assault, Not On My Campus is an organization that started at SMU in 2013.

The SMU chapter serves the role of both an SMU-specific organization and, since it was the founding chapter, also the headquarters for the rest of the nationwide movement.

Not On My Campus’ main role as an organization is to spread awareness for students, a role that fulfills a need echoed throughout the SMU student body.

“Being informed and understanding the consequences of sexual assault is a main road towards preventing it,” an anonymous SMU student said.

In addition to its role in spreading awareness, Not On My Campus also begins to break down the stigma around the burden on victims.

“We get two, maybe three emails a semester,” SMU student Catherine Pelham said in reference to the informational emails the SMU student body receives after sexual assaults have been reported. But those mere few, “that’s not an accurate representation of how many sexual assaults actually happen,” she said. “I would encourage SMU to thoroughly investigate and report every assault that happens.”

While sexual assault indeed remains a nationwide epidemic, attacking it at specific universities is an important role that Not On My Campus fulfills.

At an interest meeting on Tuesday, Aug. 30 for the organization, President Katie Butler announced the impact sexual assault would have on this campus alone. According to a 2007 campus assault study, 1 in 4 women and 1 in 16 men will be victims of sexual assault during college, that equates to 812 women and 200 men on this campus.

“For me, that’s 812 women and 200 men too many,” said head of Not On My Campus External Affairs, Sara Whiteley.

The SMU chapter also plays a role in training bystander intervention, explained Vice President Jacqui Jacoby, who elicits the role of bystanders as another road to ending sexual assault.

While finding the solution to sexual assault remains cumbersome, Not On My Campus begins the fight at SMU.

Not On My Campus applications are now open at Orgs@SMU for committee chairs. Chairs will work with other inter-campus organizations to promote Not On My Campus and work to end sexual assault.