Lauren Metzinger sits in her engineering class, pulls out her notes, and waits for her teacher to appear. Metzinger, a junior mechanical engineering major, can only recall having two women professors in the engineering department throughout her college experience.

Like in most of her classes, the teacher she is waiting for is male.

Although Metzinger thinks Lyle School of Engineering is a great place for female students, she wishes she had more female role models in the classroom.

“I think it is important to see an example of who you could be,” Metzinger said.

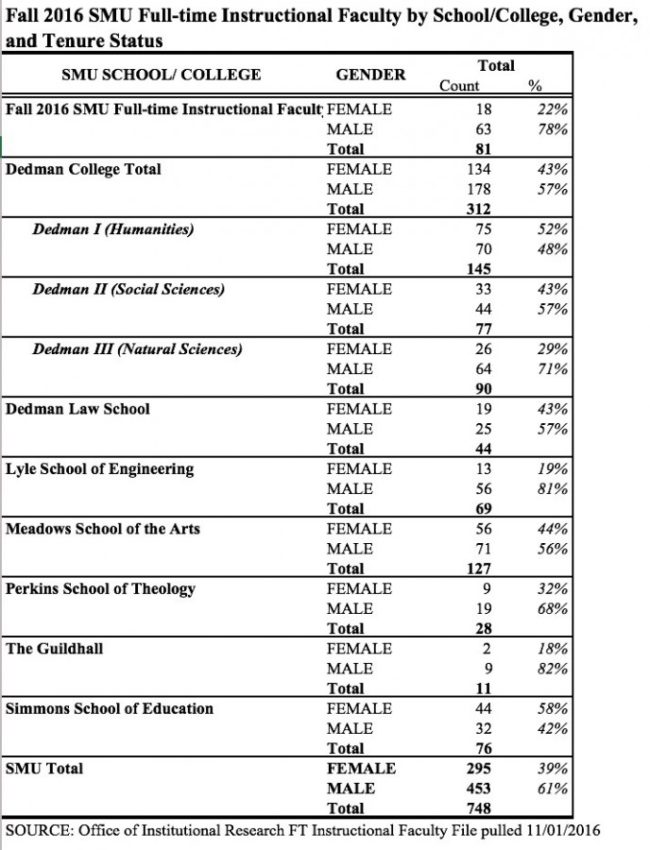

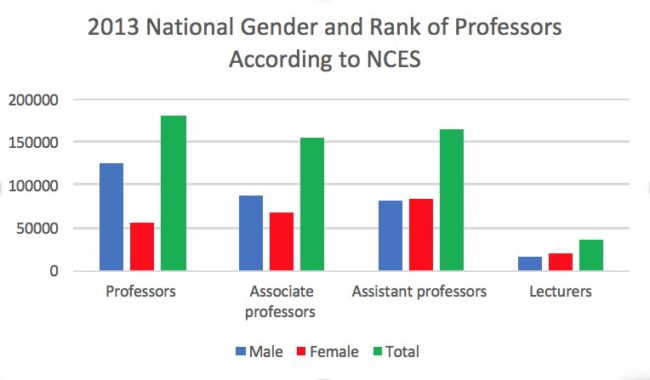

Nationally, 35 percent of professors at all academic ranks are women. SMU is just under the national average; 34.5 percent of lecturers, instructors, assistant, associate and full professors are women. Meadows School of the Arts has the most full-time female faculty at 44 percent. Lyle has the fewest. Just 19 percent of full-time faculty are women.

According to the National Center for Education Statistics 56 percent of students enrolled in colleges were female in 2014. The number of college women is expected to increase by 17 percent, while the number of college men is expected to increase by just 11 percent by the year 2025.

Today, SMU undergraduate students are split almost evenly: there are 3,242 female students and 3,245 male students.

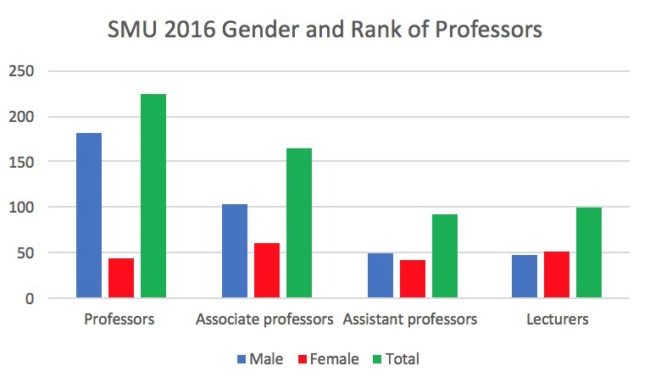

The area of most concern for SMU is the number of tenured female professors. Across the nation 45.7 percent of assistant, associate, and full professors are women. Only 26.7 percent of tenured professors at all three ranks at SMU are female.

The members of SMU’s President’s Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW) believe that the university should work to increase the number of female faculty. The PCSW creates an annual report for President R. Gerald Turner expressing the concerns of female faculty, staff, and students at SMU.

“We define it as problematic for President Turner that women are not represented to the degree that they could be in all of the disciplines,” PCSW faculty co-chair and associate sociology professor Sheri Kunovich said in a recent interview.

The gender gap almost closes when comparing the percentages of male and female teachers at lower ranks, which gives concerned faculty some hope. Women make up 52.5 percent of SMU lecturers, meaning they are not on a tenure-track. Women make up 45.6 percent of SMU assistant professors, which is the first rung on the tenure track. The percent of women begin to drop off at the associate professor level, the rank preceding a fully tenured professor position. The lowest percentage of women is found among the fully tenured professors. Only 19 percent of full professors are female.

“The worry for us as a commission is that if we are able to successfully recruit female faculty, are we also able to provide them with a professional environment that they can be successful in and be promoted,” Kunovich said.

Research, teaching and service are all considered when professors are offered tenure. Research is regarded most highly, but women participate more often in service than men. Maribeth Kuenzi, an associate professor in Cox School of Business, enjoys service but understands that it takes time away from her research.

“The committees need to have diversity, so if there are only one or two women, they get picked always to be on the committees,” Kuenzi said. “There are more men to go around at the higher ranks than there are women.”

Julia Cantú president of the SMU Feminist Equality Movement, a student organization designed to further gender equality, and Kunovich both suggest redefining the weight of each component necessary to become tenured.

“If women are choosing to focus more on service and teaching, then maybe that should be taken more into consideration,” Cantú said.

President Turner’s first goal of the 2016 – 2025 10-year strategic plan includes the objective of recruiting, promoting, and retaining a more diverse faculty. This could mean an increase in women faculty members at SMU.

Lyle has already taken steps towards achieving this goal.

Engineering associate professor Aurelie Thiele began working at SMU in August 2016. While she was being interviewed for the job, she was told that her department had a low rate of female professors and that the department wanted to change that.

“I think they do try to recruit more women but you never want to be there just because you are a woman,” Thiele said. “You don’t want special treatment.”

Another solution is to increase the number of female graduate students in fields such as engineering and business.

There is a worldwide movement that focuses on getting young women interested in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) programs. STEM campaigns created an influx of undergraduate students interested in these fields, but it will take time to see these young women in the graduate or doctoral programs.

“We are changing at the bachelor’s level and it takes time to change at the master’s and Ph.D. level, so culturally we have to look at what is the pool to choose from and, then, SMU has standards.” Kuenzi said. “We don’t want to bring in a female just because she is a female, if they are not a good teacher or if they can’t do their research.”

Thiele believes female faculty should serve as role models to undergraduate women considering careers in academia.

“The real challenge is, if you want to have more female faculty members in 20 years, you need to provide the female students today with role models so they can start thinking that they could also do this job,” Thiele said.