Nestled among rows of dense townhomes and upscale mansions across the street from Southern Methodist University’s pristine Dallas campus is a two-story brick building called the Canterbury House. Stepping inside feels like entering an idyllic suburban childhood home, with white paned windows and broken-in leather couches, but wandering just beyond the living room transports you into an entirely different world, a towering chapel with warm, wooden ceilings and rows of young people sitting shoulder-to-shoulder in conjoined chairs.

Every Sunday evening, 20 or so students gather in this building for a night of worship, fellowship and home cooked dinner, something many of them welcome as a break from dining hall food. The building is owned by SMU and chartered to different religious student organizations, but on Sunday evenings, it belongs to UKirk, a campus ministry operating under the Presbyterian Church. It receives its name from “Kirk,” a Scottish word for “church,” and is one of many branches operating on college campuses nationwide.

At the front, Liana Forss, a junior studying biology and dance delivers her first sermon as a UKirk student leader, a personal testimony where she likens her faith in God to a solo mountain hike she completed during a turbulent time in her life. Liana’s testimony is far from traditional. In it, she describes her first queer kiss not as a moment of sin, but one of celebration, self-realization, and joy.

Her story resonates with many people in the room. UKirk is a rapidly growing campus ministry with a strong LGBTQ+ presence. In many places, especially in Texas, queerness and Christianity are diametrically opposed forces, but not here. This emerging group of students holds space in themselves for what many view as conflicting identities.

Liana’s story begins not in Texas, but in Canada, where she was raised Catholic. In Canada, she says religion is not as tied to personal identity or politics as it is in America, but Liana still felt like the black sheep of her family for reasons she could not quite identify at the time. Growing up in musical theater, many of Liana’s early friends and mentors were gay men, and she recalls struggling with the Catholic perspective on sexuality, which contends that any homosexual acts are sinful.

When Liana graduated high school, she attended Oklahoma City University, where she met a passionately Christian friend and fell into a nondenominational women’s Bible study. She enjoyed spending time with this group and felt like it was the first time in her life when she could look up to the people she was learning from. “It was not the most progressive space, but at the time, it felt so wildly different from the Catholicism I grew up with,” Liana says.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Liana transferred to SMU, creating another moment of turbulence in her life. Not long after, she would find herself once again on a mountaintop, like the scene in her sermon, journaling to God. Suddenly, she had a gut feeling- a moment where she felt like queerness was “dropped” in her. “I had no reason to feel that way or to think that,” Liana says. “No femme-bodied person or woman in my life that I could be like, ‘Oh, I have a crush on this human.’” She remembers reading through her old journals looking for any precursor to this realization and finding nothing.

The following semester, Liana found herself in class with a nonbinary person to whom she felt a connection stronger than friendship. Because of the moment on the mountain, Liana says her feelings did not come as a surprise to her. This classmate, who would become Liana’s future partner, was the first person she came out to. “It was just a bunch of little steps that added up to me finally experiencing my first queer kiss that rocked my world and made me realize there’s no going back,” Liana says.

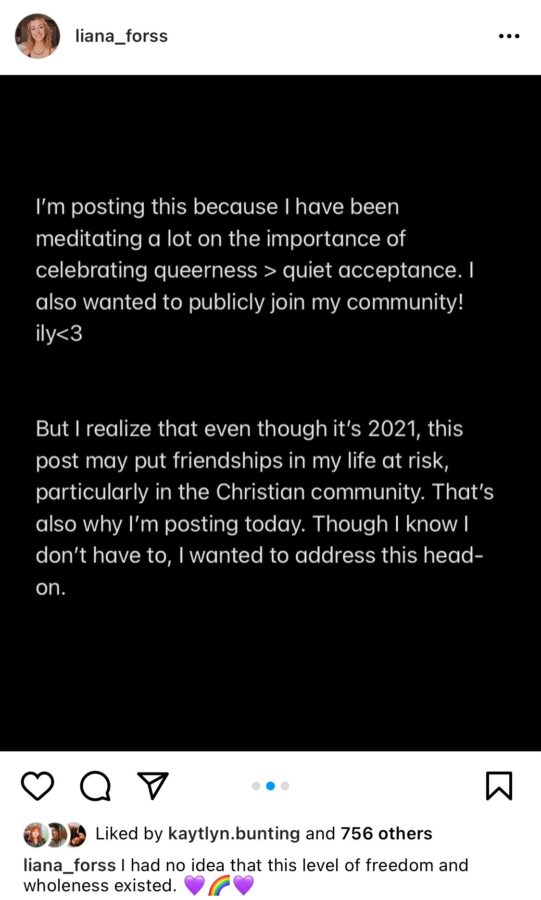

If she was going to date this person, Liana realized she would need to confront the people in her life, and especially in her religious circles, about her identity. That summer, she made an unambiguous Instagram post. The cover photo showed Liana and her nonbinary now-partner kissing in front of rainbow-colored neon heart. The following photos were screenshots of her notes app. “I do not need you to accept this part of my identity,” one slide reads. “I’m not interested in your approval when I have God’s blessing.”

She was thinking of the women in her Oklahoma City bible study when she made the post. “I had that caption in my notes app for weeks,” Liana says. “Depending on when I was feeling fired up, I would go back and alter it.”

She knew it would be shocking, given that she was a leader in that religious community. Through the post, she wanted to signal to them that she had been listening every time they made comments that did not affirm of queer identities. “I wanted to be like, ‘Hey, someone that you know, that you admire, that you look up to in terms of faith, is queer. Period,” Liana says.

Liana acknowledged her post could have prompted one of the women in the bible study to disinvite her from her wedding. After she posted it, that woman messaged her, asking Liana if there was anything she could pray about for her, and saying she was excited to see Liana at the wedding. However, at a time when Liana’s inbox was flooded with messages of support directly acknowledging the post and its contents, Liana felt like the lack of direct acknowledgement was a condemnation.

She ended up attending the wedding and reconnecting with the women from the Bible study, spending most of it explaining how her queerness and Christianity interact. Liana says many of the women wanted to be affirming before she came out, but knowing her added a sense of urgency and reality to those feelings. Some even took her advice and sought out churches with more transparent positions on issues of gender and sexuality.

Liana has noticed a growing disconnect between many practicing Christians’ personal beliefs and those of their churches. “Christians who don’t believe that being gay is a sin still go to these churches that are not transparent about their policies,” Liana says.

In certain sects of Christianity, these discrepancies are causing massive institutional shifts that leave queer Christians caught in the crossfire.

Allison Martin is a senior human rights and religious studies major who knew she was a lesbian from a young age. Like Liana, she turned to faith when coming to terms with her identity. The first person she ever came out to was her youth pastor. Church was her safe haven growing up, and she developed a passion for studying religion so intense that she went to theology camp when she was 14. “So nerdy,” she laughs.

Allison considers herself a Methodist, but has felt some distance from the institutional Methodist church for much of her recent life. In fact, it was at theology camp when she first learned of the conversations that were taking place at the General Conference for all United Methodist Churches regarding her rights as a Christian queer person.

For the past couple of years, the Methodist church has splintered over issues of LGBTQ+ inclusion in the church. At the 2019 General Conference, a 438-384 vote upheld the church’s official position against LGBTQ+ marriage and ordination, prompting those against the position to orchestrate a separation of the UMC into two separate denominations. “I’ve been waiting for this decision to happen for so long,” Allison says.

Allison attended a large Methodist church with her parents, and the developing tension over issues related to her identity placed a heavy strain on her. Her passion for religion shifted focus. “I was really involved in church at the time,” Allison says. “I thought I might be a pastor, actually. I don’t think that at all anymore.”

She was deeply hurt by her church’s refusal to take a public stance on the issue. Allison believes her church’s leadership supports the more progressive position but will not make a statement for fear of alienating congregants and more specifically, donors. “When those decisions are being made, it’s very personal for me,” Allison says.

For queer couples, the question of whether they can be married in a church is one without a definitive answer yet. Allison’s close relationship with her pastor allows her to hope that she can be the exception to the church’s official position. “He has told me that he would risk his ordination to do my wedding,” she says.

Allison wants a church wedding, but she is not completely sure it will be a Methodist one. “At this point, I don’t really consider myself that much a part of The United Methodist Church anymore because of how hurt I have been by this debate around my humanity,” she says.

Allison says she is still invested in if there will be a split in the Methodist Church. She quickly corrects her “if” to a “when.”

Liana and Allison’s distance from traditional church systems drove them together to UKirk’sleadership team. Liana found UKirk in the fall of 2020, only a year after its inception, when it was still a tiny student organization. “There were about six students that regularly attended and participated,” Liana says, “And in the span of a week, I literally ran into three of the six members.”

She had just transferred to SMU during the peak of the coronavirus pandemic and was struggling to make connections on campus. “God saw me floundering a little bit and just threw a lot of people at me,” Liana says.

After a particularly difficult time coming out to her family, Liana turned to Jessie Light-Wells, the campus minister and executive director for UKirk, talking to her on the phone almost every day. “It was a month and a half of absolute hell,” Liana says, “Jessie was my lifeline.”

Through UKirk, students learn an approach to faith that focuses on building God’s kingdom on Earth. “How can we make this place a little bit more like what God hopes and intends for his creation?” Jessie asks. For Jessie, this means crafting an environment of community outreach and inclusion. “The commandments are based on love,” Jessie says. “Not judgement or deciding who is ‘in’ or ‘out.’”

For queer students who have struggled to find their place in scripture, Jessie assures them they belong in God’s story. Even in Genesis, she says, one can find allusions to queerness in the Bible. “If you think about the creation story, there was night and then there was day. There was water and there was land,” Jessie says. “But what about all the things that fall between those things? What about sunrise? What about dawn? What about dusk? What about all that liminal space that exists between binaries?”

She believes that strict binaries, including those regarding sexuality and gender, are not God’s intention. “I read Genesis as saying, ‘God created this and this and everything in between,’” Jessie says. “If you really dig into scripture and the ways in which scripture can be translated, it starts to undo a lot of things that we have internalized about gender and about sexuality.”

Throughout Liana’s faith journey, she felt a pull toward the story of Jesus, which she contends is because Jesus’ actions in the world were queer, queer in the sense that they went against the status quo and broke the mold for what was expected of him in society. “Jesus was a refugee,” Liana says. “Jesus was born to an unwed teenager. Jesus had one of the first reported protest marches in history. Jesus was killed because he was gaining political capital that was threatening to an empire.”

She says it is “mind-blowing” that the stories of Jesus’ life have been used to espouse hatred. “At their core, they are queer, since Jesus was here for the outcasts and the outliers,” Liana says. “And who is that if not queer and POC people?”

However, even people like Allison, who feels confident in her faith and sexuality, still struggle with unlearning some of the dominant ideas about their identities. “I just have to remind myself that Christianity is bigger than this literalistic, homophobic, fundamentalist thing,” Allison says.

Allison works on UKirk’s Hospitality team, which means she arrives early to greet people at the door for Sunday worship and dinner. For some students, Allison is the first point of contact they have with the ministry. She can see how many queer Christians have been hurt by the church, and works to help them unlearn their trauma and welcome them into her community. “I see my role as showing people that it is possible to be queer and Christian,” Allison says. “You can be both, and there are communities where it’s normal to be both.”

Liana believes the Bible grants queer people the ability to experience the amplitude of God’s love, since they also experience the full force of judgement in a broken world. “Queerness should not be something that we have to reconcile with Christianity, but in fact should be a way that we experience divinity in a deeper way,” Liana says.

At Sunday worship and dinner, the energy is celebratory. “There’s definitely a feeling of gratitude- being grateful to be together, and community,” Jessie says. Every week, the group circles up to share joys and concerns. Together, they celebrate each other’s achievements and pray for whatever burdens members of the community face, everything from upcoming tests to families who won’t invite their children home for the holidays.

Jessie says the best part of being back together in person is the lingering: “People love to linger.” Dinner outside of the Canterbury House is always full of lively conversation. “There may be a group of people that’s having a conversation about deconstructing theology next to a group talking about, like, RuPaul,” Jessie says.

UKirk’s message has taken hold in SMU’s campus community. In only two years at SMU, UKirkhas exploded from eight regular attendees in its first year to a congregation of 55 today. Jessie estimates that 50% of UKirk members are queer, a staggering statistic for any student group, much less a religious one.

UKirk is the only one out of 29 SMU student ministries that is openly affirming of queer students. Even though they are the only one with this official position, Jessie is working to build bridges with other campus ministries theologically similar to UKirk. “Even if they’re not affirming, they may have students that identify as LGBTQ+ that may need that support occasionally,” Jessie says.

Photo credit: Jessie Light-Wells.

“We’re really clear from the very beginning that the LGBTQ+ people would be fully affirmed in our community,” Jessie says. “This means they are not just welcome to participate, but also that those people would have no barrier to leadership.”

The issue of queer religious leadership is a contentious one on SMU’s campus. In the spring of 2021, Adam Czarnik, an openly gay student senator noticed that some of SMU’s chartered student organizations operated under a parent company that held beliefs contradictory to SMU’s nondiscrimination policy, which reads, “SMU will not discriminate in any employment practice, education program, education activity, or admissions on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin, sex, age, disability, genetic information, or veteran status.”

This created a situation where it was unclear whether student organizations could continue to receive SMU funding if their parent organization did not comply with the policy. Adam and a handful of other senators drafted a resolution forcing organizations to add statements to their bylaws granting precedence to SMU’s nondiscrimination policy, should a discrepancy with the parent affiliate emerge.

Adam says the senate believed every organization should comply with the university’s standards. “At the end of the day, we’re in charge and we are writing the checks,” he says.

However, that summer, growing discontent from religious student groups over the resolution forced the senate to call an emergency session to revise the resolution. The revision granted an exception to religious organizations for the purpose of officers only. “Nothing in this resolution limits the ability of chartered religious student groups to select their own student officers and non-student leaders in accordance with their religious beliefs,” the amendment reads.

“I don’t like to call it a step back because I still think we made meaningful progress,” Adam says. “I like to look at it as more of a ‘two steps forward one step back’ kind of situation.” Now, it is explicitly clear that any student can join any organization, something that did not exist before the resolution. “Students are paying tuition. They have a right to be a member of every organization on this campus that their tuition dollars are going towards,” Adam says.

In September of 2021, SMU boasted on a blog post that the university was named as one of “10 Religious Schools Living Up to LGBTQ-Inclusive Values” by Campus Pride, a nonprofit focused on attainable higher education for queer students.

Adam only hesitantly agrees with that classification. He believes efforts toward LGBTQ+ inclusion are the result of a passionate and driven student body, not any university-led initiatives.

He recalls an interaction he had with a member of the administration when debates over the amendment to the resolution took place. He told the administrator he could name steps the senate was taking to be supportive of LGBTQ+ students on campus and asked the administration to name things they were doing.

The administrator cited the Bias Incident Reporting Form and the Title IX office, which disappointed Adam. “Not only is it the bare minimum,” Adam pointed out to the administrator. “It is, to my understanding, the bare minimum of what is required by federal law.”

He says the administration is not openly hostile to queer SMU students, but they are also not trying as hard as they could.

Jessie has noticed a similar cultural divide at SMU through her ministry. She says there is a dominant culture of affluence and white privilege and people who do not fit into that narrative who thrive at the university. “It’s not like they’re being pushed to the margins,” Jessie says. “They’re really truly finding places to belong.”

She believes the university is comfortable with the current tension, but within the next couple years, SMU will be forced to contend with some of the changes initiated by its progressive subculture. “If they want to become a more diverse and more competitive school, it’s going to be tense, right?” Jessie says. “Because some of that dominant culture stuff is going to have to be sacrificed to what comes next.”

As the semester comes to a close, UKirk steps away from worship nights and instead offers up the Canterbury House as a place for students to take a break from finals studying. Even on a chilly December evening, the living room is full of students. Some devour the snacks Jessie brought to the house, some work on coloring sheets, some lump frosting onto cookies while Jessie sassily roasts their design work. “Green eyes, nice,” she remarks as one student pushes two sprinkles into the white frosting of an angel cookie’s face. They need this break.

The Canterbury House’s unique architecture- part chapel and part residence- lends itself well to the role it plays in many students lives; this is a place where faith and home become one. For young people rejected by their families, their churches, or their culture, this is a community that seeks to build affirming, supportive non-traditional families.

Liana encourages anyone feeling disenfranchised by the church to seek out a community similar to the one she found and built at UKirk. “There are people out there that have lived that experience,” Liana says. “There are people out there that will not try to fix anything for you, but will just see your experience, know where you’re at, and want to be with you as you walk the road.”