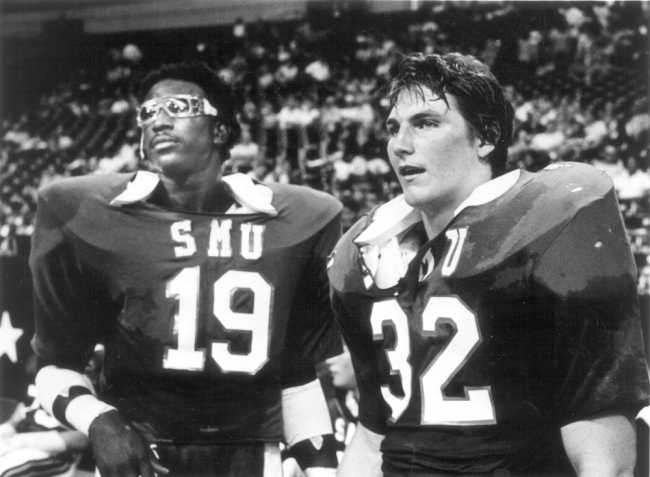

Eric Dickerson and Craig James remain two of SMU’s most accomplished college athletes. Collectively referred to as the “Pony Express,” Dickerson and James started playing Mustang football in 1979. (Courtesy of SMU)

The controversy surrounding Pennsylvania State University’s former assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky has gotten people talking about collegiate athletics and the law.

Sandusky, who is accused of sexually abusing young boys, has affected the Penn State football program in a number of ways — from the program’s reputation to its future. Although Penn State’s case is a criminal one, athletic scandals come in a variety of forms, and 24 years ago, SMU athletics experienced a scandal of their own.

“The Death Penalty,” which bans NCAA schools from competing in a sport for at least one season, halted the Mustang’s football program in 1987 and 1988, straining the spirit of SMU and the Dallas community.

A few years prior, SMU’s football team was one of the top teams in the country.

Although many football teams were involved with illegal recruitment, SMU was the first to make headlines.

The SMU Sports and Entertainment Law Association hosted two speakers on Friday that brought light to the “paying to play” topic, something that is at the forefront of ethical and legal issues in college athletics.

Kyle Conder, senior associate athletic director for compliance, joined Thaddeus Matula, director of “Pony Excess,” sharing both the legal and creative sides of the issue.

According to Matula, the Southwest Conference was the most penalized conference in the country, most of those infractions coming from SMU.

“It was a very dirty conference,” he said. “But, in that era, everything started ramping up in the 1970s.”

He stated that in the ‘30s and ‘40s, it wasn’t illegal to provide players with benefits.

“This was obviously before Dallas had the Cowboys,” Matula said. “SMU was Dallas’ team.”

Dallas was busting with money in the late ‘70s to early ‘80s when the scandal came to fruition.

“SMU decided it was time to play with the big boys,” he said. “And it got out of hand.”

However, SMU was not the only school that was doing this.

“SMU has the unfortunate distinction of being caught and not being able to distance itself institutionally from the violations,” Conder said.

According to Conder, institutional decisions are a big part of what dictates a school’s future after scandals.

“The institution made the decision we have to stop these payments, but we are going to try to control them,” he said when describing SMU’s scandal in the late 1980s.

Conder then went on to explain how SMU did not permit recruits to make campus visits after “The Death Penalty” until they had been admitted or they were clear qualifiers by the NCAA.

The importance of institutional decisions can translate to Penn State today.

“If Penn States’ attitude is look we are going to clean house with the coaching staff but otherwise it’s business as usual here, in terms of recruiting activities and the amount of resources we provide for the program, it [their recruiting] may not change very much,” Conder said.

Just as SMU got through its’ scandal, Penn State will too. It’s just a matter of time.