“We don’t all have the privilege of tracing back our lineage because, newsflash: we were stolen!” said junior Abena Marfo with a roll of her eyes. This classroom encounter, she said, highlights the racial tension she and other Black students often encounter on campus.

Marfo, who is studying sociology and health and society, said she was enrolled in a course this summer that required her to trace back her lineage. Marfo has more access to her family history than the average African-American, but not even that could alleviate the trouble she had conducting her research.

“Even with family back in Ghana, there was never a great job keeping track of things,” Marfo said.

Marfo said she was frustrated that her project might suffer because of something completely outside of her control. When she voiced her concern to her sociology professor, the teacher pushed her to work even harder to find substantiating documents.

Marfo was less worried about her grade in the class than she was about her professor’s apparent ignorance of the racial disparities highlighted by the assignment.

“That was probably one of the most difficult things I’ve had to deal with, especially coming from a professor that I actually like,” said Marfo.

Marfo is not the only Black student who has suffered racial tensions, ignorance and confusion in the classroom and across campus. Students and faculty say that addressing and handling these uncomfortable situations with competence and respect is integral to improving Black students’ educational experiences in these tumultuous times.

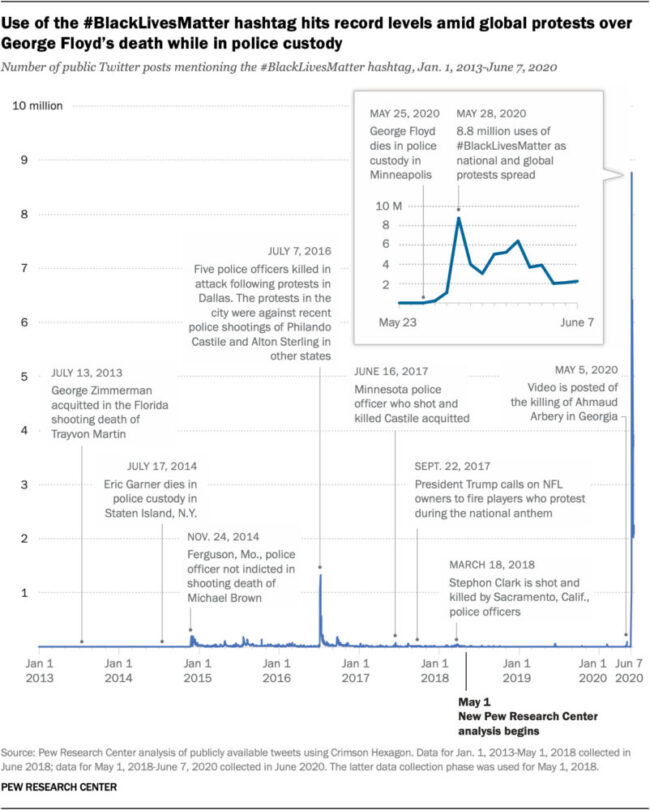

Racial tensions are peaking across the nation, including at universities. The United States is in the middle of one of the largest social upheavals in a century. On May 25, a Black man, George Floyd, was murdered in Minnesota by Derek Chauvin, a white on-duty police officer during an arrest. Chauvin’s death, and the video footage released by eye-witnesses, was a major catalyst for widespread protests of police brutality that persist even now, four months after the incident.

The Pew Research Center reported in June that the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag had been used 47.8 million times on Twitter – an average of just under 3.7 million times per day – from May 26 to June 7.

At SMU, Floyd’s death is forcing students and professors to once again reckon with a century of racial tensions. Navigating the campus in the face of societal unrest is far from a new dilemma, but the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement has seen student groups old and new such as the Association of Black Students and the Black Student-Athlete Committee dedicate themselves to organizing protests and marches.

Student groups at SMU have made demands of university leaders over the decades to engender a more tolerable student experience. In 1969 the Black League of Afro-American and African College Students (now the Association of Black Students) demanded the total Black student population be increased to 500 (unmet), and recommended a University funded recruitment committee consisting of Black students (unmet). In 2015, they demanded Black undergraduate enrollment be increased to 10% of the undergraduate population (unmet). In 2020, the demands were updated again, with many of the previously unmet demands elaborated upon. SMU has a track record for acknowledging these demands publicly, and meeting only a fraction of them.

Erica Zamora, director of SMU’s office of Social Change and Intercultural Engagement (SCIE), is on the university’s Bias Education Response Team. She often hears from students who have been deeply affected by racial insensitivity across campus, including in classrooms.

“I want to share how many students I have heard say, ‘I like my professor. I think that they’re brilliant and I have enjoyed their class, but this hurt me so badly that I don’t know that I can look at them in the same way,’” Zamora said.

Zamora emphasizes how fragile the trust forged between students and professors is, and how difficult that trust is to regain once it’s been lost.

“That idea of, ‘well, that’s not what I meant’ sometimes doesn’t matter,” Zamora said. “It’s ruined something so quickly.”

The negative effects of racial insensitivity on Black students is compounded by feelings of intense isolation in the classroom.

“Out of five classes within a semester, sometimes three to four will have one other Black person,” Marfo said.

Black students in other departments cite the same experience.

Senior English and Sociology major Matt Jackson could count on his hands the number of times he’s been in a classroom with more than one other Black student.

“Maybe once a year,” Jackson said, “depending on what I’m taking.

Karen Thomas, one of the few Black professors at SMU, also noted this trend. She said that in her dozen years here she has not had many Black students in her classes.

“Maybe one per class if I’m lucky, some classes none at all,” Thomas said. “The most I’ve had is maybe two black students at the same time.”

This is not surprising: in the Fall of 2019, Black students made up 4% of the undergraduate student body. In 2019, there was a total of 31 Black instructors employed at the University, about 4% of total instructors. It is inevitable that Black students will be vastly outnumbered in most of their courses.

This past summer, Black students and alumni took to Twitter to share their experiences at SMU. Many of them were negative, citing the same issues of isolation and ignorance that the University has been dealing with for years.

Was the only Black person in my freshman year DISC class and we were reading heart of darkness (which is about British colonization of Congo) and during a discussion this white girl kept referring to the people of Congo as “savages” #BlackatSMU

— Hanan. (@hananxmontana) June 2, 2020

https://twitter.com/cheysces/status/1267942822067519489

Black students are not the only ones concerned about the consequences of racial tension in the classroom. SMU sophomore Brooke Betik recalls an incident where her professor said that his own college professors said the n-word in class. Betik relayed this story to one of her Black friends, only to find that he’d had a similar experience during his time at SMU.

“That blows my mind,” Betik said. “That would shake me and I’m not even the life directly affected by the slur.”

Betik, a white student, takes care to position herself as an ally to her peers. She said that the key to her activism is to flag herself as someone willing to listen and learn. But, she went on to insist, that cannot be where your activism ends.

“Actually educating yourself on anti-racism, and actively doing the work on your own is the only way that anything will ever get changed,” Betik said.

Betik’s advice isn’t limited to students. She said that SMU professors and other staff members would do well to remember that they are not exempt from learning and growing.

“You might have a Ph.D. in whatever you’re teaching, but that doesn’t mean you know everything about how to be a good human,” Betik said.

The advice that Black students gave from improving their classroom experiences were the same. Marfo implored professors to resist their instincts towards neutrality on controversial topics. She said that she would much prefer a vocal ally in a professor than one who remains silent.

“There’s no such thing as middle ground,” Marfo said. “It’s either you are for it or you are against it, and I need professors to make that clear right off the bat.”

She can recall several situations in which classmates made racially charged comments that went unpunished by professors. She doesn’t like the feeling of having to fend for herself in the classroom and calls for professors to acknowledge the offending students in the same public forum in which they chose to make their comments.

“I’m not asking for much I’m just asking for my human rights,” Marfo said.

SMU sophomore Sparrow Caldwell said she often feels personally responsible for reminding the class there are people who experience life differently than they do. She resents the expectation often placed on her to educate her peers.

“The information is everywhere,” Caldwell said, “so don’t look at me to correct you, or explain it to other people unless you’re paying me.”

Jackson cites a similar experience in one of his English classes, where they were discussing the topic of colorism in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. Throughout the conversation he felt eyes on him seeking explanation, ignoring the reality that he is a student just like they are.

Jackson understands that racial tension in the classroom, as a direct byproduct of racial tension in the country, cannot be eradicated. He does, however, believe there are many ways it could be more effectively addressed.

“Really look out for your Black students,” said Jackson. “Consider them first when you’re addressing topics that may have direct impact on their lives or may be ties to their history as people.”

Jackson specifically requests that professors refrain from putting pressure on Black students when it comes to discussing slavery or racism.

“They’re students,” said Jackson. “They’re trying to learn about it. You prepared a lecture, and they want to hear it just like everybody else.”

This reminder was echoed by Professor Thomas, who teaches a course on women and minorities in the media. She said she considers it her job to introduce white students to some of the more difficult topics in her class. The tricky part, she said, is managing that without alienating the students of color in her class who already understand these things.

“I don’t ever want a student of color to feel like it’s their job to share their experience or educate their classmates because it’s not,” Thomas said.

One of the ways that Thomas manages this balancing act is to pace her curriculum so that she can focus on neutral topics early on. She doesn’t bring up contentious issues until she knows her students better, so that she has an idea on how to best lead discussion.

“If I do it too fast I don’t really know who’s sitting in the room with me,” she said, “and so it’s harder to understand the dynamics that might unfold.”

Thomas also establishes early on that her classroom is a safe space for students. She said that she’s found that the best way to ensure students know that is to tell them. To let them know outright that she will try her best to treat them with respect and dignity, and refrain from making them feel ostracized.

“I like to make sure that the students understand who I am, where I’m coming from, and that I’m not gonna do that to them.”