Few were surprised when reported cases of COVID-19 on campus spiked soon after students returned to campus in late August. At the peak of new infections the week of Sept. 6, SMU reported 175 new weekly cases, and over 260 active cases. Yet the numbers dropped as quickly as they spiked. One week later, the week of Sept. 13, reported cases dropped to 83, while active cases fell to 163. On Sunday, Sept. 27, SMU reported 0 new daily cases, just one month after the school year had begun.

Some SMU students don’t believe the lower numbers. Photos of unmasked students at off-campus gatherings and local bars like 77, Ice House, and XOXO have circulated on social media since August. Students also say that sick students take advantage of the university’s reliance on self-reporting and never disclose their positive off-campus test results, lie to contact tracers, or avoid testing entirely. Without widespread testing of the campus population, some say it is impossible to know how many students are actually sick.

Read More – Commentary: SMU Students Party Despite Pandemic Restrictions

“I think a lot of people are getting tested elsewhere and then not reporting so that they can quarantine (or not) on their own terms and not the school’s.” wrote one user on a SMU Reddit forum. Another user shared that they had been in group calls with friends who had lied to contact tracers to avoid university-imposed quarantine.

The main cause of the initial spread appeared to be students socializing on and off campus, according to Environmental Health and Safety Director Brandon Chance, who said that students now appear to be focusing more on their studies and more carefully following the health guidelines, resulting in lower case numbers. Chance pointed out, however, that it was vital for students to continue following university health guidelines and the commitments in SMU’s Pledge to Protect to limit infections.

“The Pledge to Protect extends past the boundaries of the campus,” Chance wrote in an email interview. “Contract tracing does help mitigate the spread, but it is important for students to be honest in reporting positive cases and identifying contacts and to follow the guidelines for quarantine and isolation.”

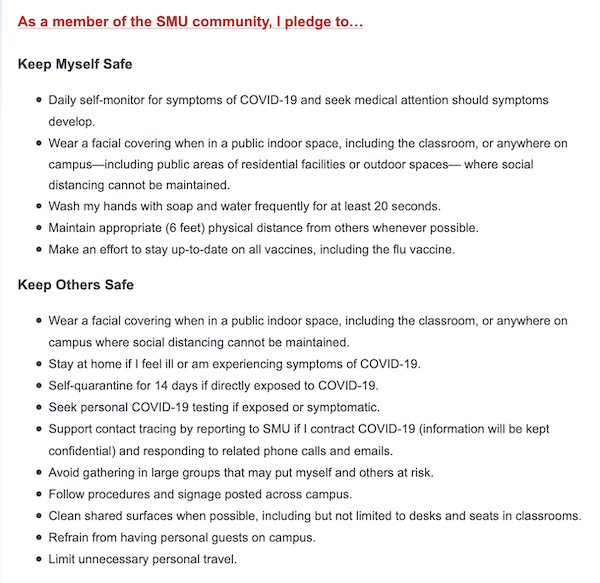

SMU required all students and employees to take an online COVID-19 safety course and sign the “Pledge to Protect” before returning to campus in August. The mandatory pledge requires that students avoid large, off-campus gatherings, seek personal COVID-19 testing if exposed or symptomatic, and to report their confirmed cases to the university. However, SMU’s overall testing plan did not include entry testing, which would require all students to be quarantined and tested upon their return to campus. The school focused instead on using contact tracers to identify and isolate positive cases while quarantining those who were exposed to the virus.

Some infected students don’t disclose their illness to avoid university isolation and quarantine restrictions on themselves and the people they may have exposed, according to one SMU junior. The student asked to remain anonymous to protect his privacy and the privacy of his friends. While some sick students who don’t report their illness will isolate themselves, the student, a French and business major, claims to have heard at least one other student announce his intentions to go out to a party despite having just tested positive for “’rona.”

“I know people from school who have gotten COVID by going out or seeing people who did not tell them that they had it or had just tested positive,” he said. “If they put their friends in any contact tracing, then they’ll have to be online and then it just really restricts people.”

Read More – First Week Back: COVID Parties, Students Denied Testing, & Virtual Class Disasters as Cases Exceed 100

SMU’s testing and contact tracing plan relies heavily on student disclosure for its accuracy. With the exception of student athletes, students are only required to be tested if they display coronavirus symptoms or if contact tracers determine that they were in close contact with someone who tested positive for the virus. Those in close contact are asked to quarantine, while those who test positive are given the option to isolate on campus or at their home.

When asked whether SMU’s testing plan could overlook asymptomatic cases, Chance wrote in an email interview that SMU’s symptomatic-focused testing policy follows CDC guidelines. Chance included the CDC’s statement in his email, which stated that there were still insufficient studies to confirm if entry testing at universities prevented virus transmission more than other measures like masking, social distancing and hand washing.

“Therefore, CDC does not recommend entry testing of all returning students, faculty, and staff,” Chance wrote.

The CDC published new considerations on Sept. 30, the day after Chance spoke to The Daily Campus, to say that testing can be an avenue to reduce campus transmission by identifying unconfirmed, mild, or asymptomatic COVID-19 cases.

Even so, SMU and other Texas universities were already reporting dramatically lowered case numbers by the time CDC updated its considerations. Baylor University, the University of North Texas (UNT), Texas A&M, and TCU, have all seen similar patterns of spikes followed by sudden dips in reported cases. University and county data suggests that overall cases are trending down, but some students suspect that limited campus testing is also artificially lowering the numbers.

“I think the biggest issue is not necessarily people aren’t reporting it to contact tracers, but that people aren’t getting tested at all,” said Megan Menchaca, managing editor or UT Austin’s student newspaper. “UT did require everybody who went to the football game to get tested, which resulted in a very high number of cases. That, to me, kind of shows that there’s more cases behind the scenes that we’re not catching because people aren’t getting tested.”

https://twitter.com/onlinelonghorn/status/1315110604286423042?s=20

SMU has an undergraduate enrollment of about 6,479 students according to its campus profile. At the peak of its daily testing activity, SMU was directly testing about .009% of its undergraduate student body. Now, it is testing about .002% every day.

“We’ve gone from testing a high of 50 to 60 students to now testing 10 to 15 students a day,” Bob Smith Health Center Executive Director Dr. Randy Jones said in an email interview in late September. “The demand for weekend testing has dropped off considerably as well.”

No matter the true numbers, many students do seem to have adjusted to the lingering presence of COVID cases, social distancing, and masking. For students like first-year rower Anne Ensley, this “new normal” now just feels normal.

“I think if you make the choice to come be on campus this fall, it’s a risk you’re going to have to take,” Ensley said.

Having contracted the virus before the semester began, the anonymous SMU junior believes that the country, as a whole, did not take enough measures to confront the virus during its early spread. He doesn’t support student behavior that puts themselves and others at risk of contracting COVID, but acknowledges that barely anyone expected the severity of the spread to require putting life, work and school on hold for longer than the summer.

“I would say the biggest factor is that people really were trying and then they got fed up because they either got the virus or they haven’t seen any progress,” he said.

For the majority of college students who are young and away from vulnerable family members, the potential threat of the virus simply feels removed from their immediate lives.

“They don’t care about coronavirus – they have jobs and classwork,” Menchaca said of students at UT and other universities. “I think anything extra on top of that, like spiking cases or issues with testing or positivity rates, just isn’t what they want to be worried about unless it really dramatically affects them. Which, right now, it isn’t.”