As a senior in high school exactly four years ago, I faced a difficult decision of where I would attend college. Having just gotten my rejection letter from Princeton, I was down to Vanderbilt, UNC-Chapel Hill, SMU, and the University of Georgia. My mom, a graduate of Carolina, desperately wanted me to go to Chapel Hill. My dad, who wanted to pay in-state tuition, was pushing for UGA. Both of my brothers told me to go to Vanderbilt.

Much to everyone’s surprise, I chose SMU.

Since I made the decision to go here, I’ve always been quick to compile a list of reasons out why I think SMU was the best choice. We just finished a $1 billion capital campaign, we’ve steadily risen in college rankings over the past decade, we’ve improved our average SAT by over 100 points since 2004 and our campus is in the heart of an ever-growing major city. All signs point toward an upward trajectory for SMU.

But will SMU continue to rise to the top?

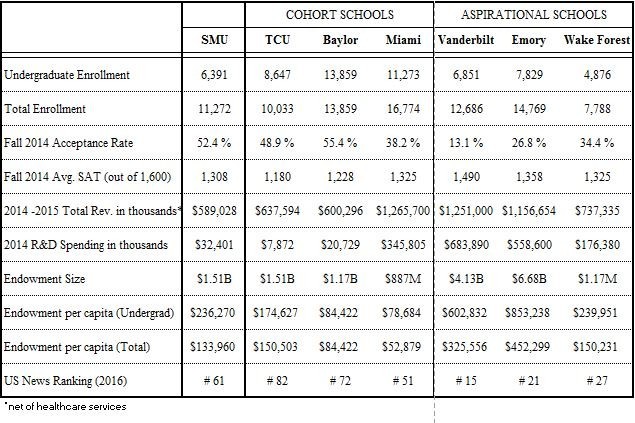

A 2012 report from SMU’s administration compares our school on a variety of different metrics to a group of “cohort” schools, or those that are most similar to SMU, and “aspirational” schools, or those that SMU strives to compete with. In many aspects, our campus is well on its way to leaving its cohort schools behind and becoming more like its aspirational schools. But there are still several fundamental differences related to our operating budget that separate SMU from its aspirational schools. I selected a group of three cohort schools and three aspirational schools that I think are most similar to SMU and compared our budgets with theirs.

About 11 percent of SMU’s annual revenue comes from endowment distributions, according to a recent memo from SMU president Dr. R. Gerald Turner. This percentage, while higher than our cohort schools, will likely have to increase in the future. Roughly 70 percent of SMU’s revenue comes from tuition, and nationwide pressure to curtail tuition growth at private universities is causing schools to rethink budgets. SMU needs to find new ways to supplement its revenue with this slowdown in tuition growth.

“Revenue growth is slowing down,” said Dr. Nathan Balke, economics professor and chair of SMU’s All-University Finance Committee. “So either you’re going to have to find new sources of revenue…or you’re going to have to cut growth and costs.”

Typically, a university allocates around 4.5 percent of its endowment toward operating expenses each year. SMU targets this percentage annually, which means about $68 million in revenue for the current academic year. Assuming Vanderbilt and Emory also put 4.5 percent of their endowment value toward this year’s operations, the distributions would provide $186 million and $301 million, respectively.

$301 million is equal to 51 percent of SMU’s entire operating revenue from the 2014-2015 school year.

Dr. Balke said SMU should consider drawing down more than the typical 4.5 percent of its endowment for operating expenses. Because SMU is such a young university with a young alumni base, it could afford to draw more money from its endowment in the near-term to meet budget shortfalls.

“In the future we’re likely to be able to have more giving by our alumni, so we’re going to be a richer university,” Balke said. “Why save a lot when you’re going to be rich in the future? Why not use some of those endowment resources today to help build the university?”

Before his resignation, former SMU chief investment officer Mike Condon thought the spending rate from the endowment would remain at 4.5 percent going forward. Condon expected a long-term average return from the endowment fund “of approximately 9 percent annually, or 5.5 percent after an expected average rate of inflation of 3.5 percent.” By limiting spending to 4.5 percent annually, “the original value of the funds…would be preserved and invested, while the earnings would support the funds’ purposes,” Condon said.

Another way SMU could improve its financial position is by adding more continuing education programs. According to Turner’s memo, the school is “undertaking an extensive study of universities in major cities that have large continuing education programs, whose profits provide support for their universities.” Balke said these types of programs could provide significant profits for SMU that could help pay for currently underfunded programs.

“For example, in the economics department we have an applied master’s program, and almost all of our students are full fee paying students,” he said.

While new master’s programs would provide additional sources of income for the school, Dr. Balke said Ph.D. programs would do the opposite. “Ph.D. programs generally are fairly expensive because the school supports the graduate students in those programs rather than having them pay.”

From a budget perspective, SMU also lags behind most of its aspirational schools in the money it receives for sponsored research and development expenditures, according to Turner’s memo. According to a report from the National Science Foundation, SMU only spent $32.4 million on R&D in 2014, less than every single one of its aspirational schools. While Vanderbilt, Emory and Wake Forest dwarf SMU in R&D spending, most of that money can be attributed to their research-heavy medical schools. In order to compare apples to apples, we can look at Notre Dame, which is one of SMU’s aspirational schools that does not have a medical school. Still, Notre Dame had R&D expenditures in 2014 of $182.2 million, or about six times SMU’s expenditures.

Balke said that most research spending gets funded through government research grants, and schools typically get to keep a cut of that funding. He thinks hiring expensive, high-quality faculty could help SMU earn new sources of income through research grants.

“To be able to get those research grants, you have to have high-quality faculty members…and you have to have research infrastructure, like labs,” Balke said. “It’s kind of a catch-22. You’re going to have to spend some resources to earn the resources.”

SMU raised roughly $1.15 billion through its Second Century Campaign, which may help alleviate some of the budget pressures. While much of the money will go toward new buildings and renovated facilities, $327 million was committed toward operations and $362 million was reserved for endowment purposes. The endowment donations have added hundreds of new scholarships and over 50 new endowed faculty positions. These donations will likely help relieve some of the pressure between tuition revenue and faculty salaries.

In 1997, Vanderbilt University had an acceptance rate of 58.3 percent and an endowment valued at $1.507 billion. Sounds a lot like SMU today, right? Less than two decades later, Vanderbilt accepted just 13.2 percent of its applicants and had an endowment value of $4.13 billion.

Let’s see where SMU is in 2035.