By Madeleine Kalb

A Gucci travel bag topples off the top shelf of Leroy Poignant’s overwhelming closet. The 6-foot-5 sometimes model tosses ties over his shoulder while shouting their designer labels.

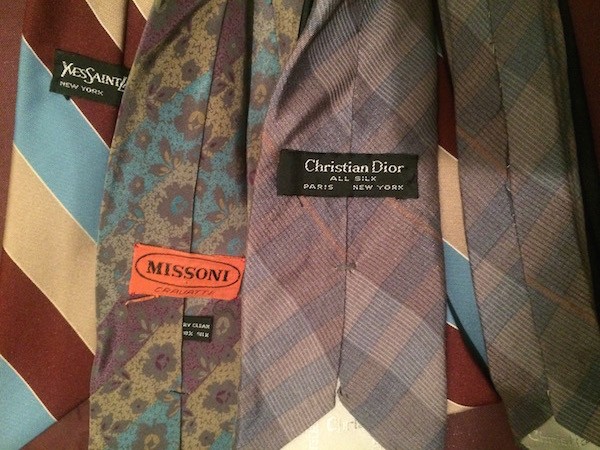

“Hermes, Valentino, Christian Dior, another Christian Dior! A Pierre Cardin with a $600 tag!” Poignant exclaims.

Over the past four years, Poignant has accumulated over 100 ties stamped with exclusive designer tags and sees no end to his massive, ever-growing collection. A few ties are neatly protected in a leather carry case, some hang on a rack, and many are shoved wherever they may fit in one of Poignant’s walk-in closets.

“I guess I will never have enough,” Poignant, an Art Institute of Dallas student, said. “Oh my gosh, there really is no number.”

Even Poignant agrees that his tie collecting has gotten out of control. Shopping addiction and compulsion is a commonly shared experience that is not particular to gender, age or any other demographic detail. Rich or poor, it is a commonly shared experience that is rarely discussed.

The DSM 5 is a mental health manual that health professionals in America use to diagnose mental health disorders. Healthcare professionals refer to shopping addiction as “compulsive shopping” or “compulsive buying” because there currently is no DSM 5 diagnosis for this behavior. Oftentimes, the compulsive shopping behavior is grouped under the addiction umbrella. Kay Colbert, a licensed therapist and addiction specialist in Dallas, attributes the non-diagnosis to a lack of evidence-based research at this time.

“Most addictions or compulsive behaviors follow similar neural pathways in the brain,” Colbert said. “They involve the dopamine reward system.”

Compulsive shoppers/addicts crave the dopamine rush they get from making purchases and chase the rush at any fiscal or personal risk. Colbert also says that mental health professionals believe that compulsive shopping follows a similar pattern to other impulse control disorders such as gambling, shoplifting, sex, eating, gaming and more.

Shopping becomes a problem when it begins to interfere significantly in a person’s life. According to Colbert, when a person begins to suffer negative consequences in his or her daily life, it has become a disorder. Work, school, health, finances, sleep and family relationships may suffer because of a person’s disorder.

Hayden Fairbrass*, a San Antonio native and executive director of an arts organization in Dallas, experienced this firsthand in his early 20s.

“By the time I was 24, I was in immense debt, Fairbass said. “I was out of control. I was living way beyond my means.”

From age 18 to 24, Fairbrass was a top national salesman for Baccarat Crystal at the Saks Fifth Avenue flagship in San Antonio. Unfortunately for Fairbrass, the Saks Fifth Avenue employee discount and the abundance of luxury designer products were all too tempting, and his paycheck would go right back into the company.

“At 18 years of age, a $1,000 outfit was the norm. With my employee discount, it wasn’t unusual for me to be buying these outfits,” Fairbrass said.

Fairbrass would purchase new outfits every weekend. These chic and high fashion outfits gave him access to the nightlife and hip club scene in San Antonio. He became addicted to the lifestyle as well as the dopamine rush of making purchases at discounted prices.

“It was very easy to accumulate debt. You become a product of your environment,” Fairbrass said. “Dressing well is about perception. It is about looking like you have money. I was the only male student in my high school to have Gucci loafers.”

Discount upon discount, the luxurious life that Fairbrass was buying into came crashing down.

At 24 years old, Fairbrass’ debt had become overwhelming. He recalls using his paycheck to purchase new outfits, taking cash advances on his credit card to pay his bills, and then using credit cards to pay for the nightclubs and lounges. His debt became so consuming that his parents had to intervene and help make payments.

“The lifestyle and living in the moment was more important then the debt. I would tell myself tomorrow, tomorrow I will pay it off,” Fairbrass said.

Colbert describes this behavior as the reward cycle that addicts experience. When the person engages in the behavior (shopping), the brain produces a burst of dopamine. Dopamine makes the person feel good, like going on a rollercoaster. The person engaging in the shopping behavior experiences pleasurable sensations and feelings that make them want to do it again and again.

“Sales gave me a rush. To see a $300 shirt on clearance for $100, I had to have it,” Fairbrass said.

For a person with addictive behavior, Colbert said, the cycle of pleasurable feelings would eventually become harder to attain. The brain will adapt to the cycle and research shows that it will begin to produce less dopamine, making it harder for the person to feel the reward and soothe his or her anxiety. The person is now running on a dopamine deficit and needs to engage in addictive behavior more often.

“Addicts are not bad or weak. They have a disease that may be controlled with lifestyle changes, behavioral changes, and possibly medication,” Colbert said.

Division 1 athlete and senior at Southern Methodist University Sarah Smith* has experienced shopping compulsion, but on a much smaller scale. Smith is a scholarship student and struggles to keep within her limited budget.

“I have bags from H&M and Victoria’s Secret that are in my trunk right now, filled with stuff that has to be returned,” Smith said.

Smith explains that she gets stuck in a vicious cycle of “what is 20 more dollars?” Then she’ll find herself slamming her head on her steering wheel in a shameful epiphany, realizing she just spent her gas money. Smith said, that in just this past month, she has been to H&M to buy and return items four times already.

“Once I realize how much I’ve spent, I feel anxiety – but in the moment I don’t,” Smith said.

Smith said that she will see an item – for instance, most recently a strapless blouse at H&M. She then envisions herself at brunch in this top and purchases it for $12. After the purchase, she realizes she needs a strapless bra to wear the top. Smith walks out of H&M and across the hallway of NorthPark Center to Victoria’s Secret, where she will find a strapless bra on sale for $20. After being on a dopamine rush of scoring great deals on sales, she will wonder what else is on the shelves at VS and walk out of the store spending $180.

“I don’t even tell my boyfriend that I spend money I don’t have. I just tell him I have to return stuff,” Smith said. “I don’t tell him how much I spent or the thought process behind it. I just say I’m returning it because it’s not as cute as I thought.”

Smith is experiencing a vicious cycle that she cannot afford and feels trapped in. Sometimes, Smith said, she walks into a store, picks items up and purchases them without trying them on in order to force herself to leave the store. She will then get home and realize what she has done and go back to return the item.

“I will return it. But when I get back to the store and realize there is something new on the shelf that is relatively the same price if not a dollar more, the cycle starts again,” Smith said.

According to Colbert, the compulsive shopper is experiencing feelings similar to those of an alcoholic. An alcoholic may say, “I’ll just have another beer,” while a shopping addict may say, “Well, I’ll just buy a lipstick because I need it.”

“The person is most likely experiencing physical symptoms at this point – heart racing, faster breathing, increased levels of anxiety and tension,” Colbert said.

As soon as the compulsive shopper realizes what she has done, reality ensues. She realizes she has made a mistake.

“Purchasing the items gives her a sense of relief, perhaps euphoria for a short period,” Colbert said, “Then this fades, and eventually negative feelings will develop – remorse, guilt, shame.”

Soon after these feelings, the person will say he or she will never do this again and then the cycle repeats itself. Colbert said these tendencies describe the experiences of a current patient. The patient is a 50-year-old, divorced white female who goes on huge shopping binges at the mall. When the euphoria of the binge is over, she returns all the items a day later. Colbert said that the woman realizes that she didn’t even want these items. This woman creatively solved her addiction by freezing her credit cards in a big bowl of water. Colbert added that by the time the woman could thaw her credit cards out, her compulsion had passed.

The nature of addiction is to lose control of one’s actions. Colbert said that short-term rewards create persistent behavior and that, despite the realization of the negative consequences, the neural pathways in the brain are being set and wired to seek the euphoria.

Many compulsive shoppers struggle to find a balance or a healthy solution to handle their disorder. Poignant has managed to satisfy his tie collecting compulsion and other shopping desires with a fiscally responsible alternative.

Although he may be amassing an unusual amount of designer ties, Poignant said that he spends no more then $5 per tie. In fact, he said he picked up a bag of Christian Dior and Hermes ties in Galveston, Texas for a mere $1 per tie. His secret? Thrift shopping.

Through thrift shopping, Poignant is able to satisfy his craving of acquiring designer pieces but in a financially responsible manner that won’t cause him harm.

“I could go to the mall and buy a $60 Ralph Lauren shirt, but why would I do that when I can go to a thrift store and spend half of that for 20 Ralph Laurens?” Poignant said. “It just doesn’t make sense to me.”

Some of the ties in Poignant’s collection have original tags marked upwards of $1,000. Poignant gets a thrill and a high of acquiring these coveted designer pieces at almost for free price tags.

“I have an addiction in the sense of going to a thrift store and needing to buy something. Even if I walk out with one tie, which I won’t spend over $5 on, I’m okay to go home,” Poignant said.

*Name has been changed to protect the privacy of the individual.