After paying her monthly rent of nearly $1,000 for an apartment on Mockingbird Lane, SMU women’s soccer player Hannah Fleet says she has only $500 remaining for the month. Out of the $500, she pays about $50 for electricity and $100 for her phone bill, leaving her with $350 for her other expenses.

Fleet, a junior, has practice early in the morning, so making breakfast is difficult. Along with practice, class and meetings, she rarely has time to cook and inevitably eats most of her meals out, using up most of the rest of her spending money.

“I have to borrow money from my parents because we don’t get checks on certain months,” Fleet said. “It would be nice to have some extra money in my pocket to spend freely.”

Fleet, along with some other SMU student athletes, would like the NCAA to construct a plan that compensates athletes for the countless hours they spend on school and their respective sports.

“I believe that other athletes as well as myself should get paid because of all the jobs we generate in society,” junior runner LaTessa Johnson said. “The only question is how much should they get paid and should everyone receive the same amount.”

Matt Robinson, associate director for Student Athlete Academic Services, sympathizes. He said the amount of hours student athletes spend per week on sports and studies takes up most of their time.

“Having the discussion about how much time there is in a week, which is 168 hours, and then compare that to how many hours the average person spends working a full-time job, which is 40 hours per week, while comparing that to a student-athletes schedule, college athletics is like having a full-time job,” Robinson said.

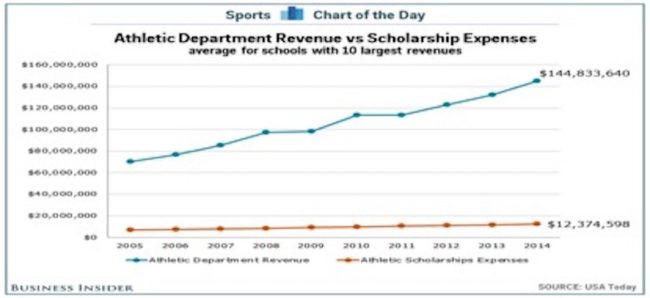

The NCAA is a multi-billion dollar sports business. Millions of dollars come from TV contracts, merchandising deals and brand deals like Nike and Adidas. According to researcher Ryan Vanderford, the NCAA made $871.6 million in revenue in 2012.

Coaches and athletic directors from powerhouse universities earn millions each year. For instance, SMU head basketball coach Larry Brown, made $2,215,486 in 2015, according to the university’s 990 federal tax form. Assistant coach Tim Jankovich made $559,644.

Although these two coaches and the university make millions from ticket sales, donations, media rights, branding and other revenue streams, the athletes don’t reap any financial benefits. This is a problem for many athletes, because they are the ones who put the fans in the seats and fill the stadiums.

The conversation about paying college athletes has been going on for years at universities across the country.

According to the NCAA, athletes must remain as amateurs to remain eligible to compete in their respective sport. Amateurism means athletes are prohibited from receiving money or gifts in any form. The amateurism requirements do not allow “contracts with professional teams, salary for participating in athletics, prize money above actual and necessary expenses, play with professionals, tryouts, practice or competition with a professional team, benefits from an agent or prospective agent, Agreement to be represented by an agent or delayed initial full-time collegiate enrollment to participate in organized sports competition.”

This long list of rules and guidelines that athletes must follow to remain amateurs can be grueling and annoying when they know how much time they commit to sports.

“We work nearly just as hard as paid pro athletes, whether or not we have a scholarship or not, and the hours we spend training could also be spent studying or working at a paid job,” junior rower Stephanie Carr said.

A full-ride scholarship covers tuition, books, student fees, and room and board. The majority of SMU athletes who play on the most popular teams like football and basketball, which bring in the most revenue, are on full-ride scholarships and reap the benefits of receiving a free education.

For other sports such as soccer, swimming, and track and field, which generate less revenue, not all athletes receive full rides. Some only receive partial scholarships which could cover just tuition or books.

Some SMU students, however, think paying athletes is paid. To them, getting a scholarship is enough.

“I think athletes shouldn’t get paid because in a sense, they are already being paid with scholarships,” junior Jose Ranz said. “I like going to the games and cheering for my school teams, and I think the players should be playing to keep improving and work hard instead of playing for the money.”

Paying athletes comes with advantages as well as disadvantages.

“With money being an extrinsic motivation for most people, paying athletes would put them in a greater mood, and their morale would be higher about everything going on in their life,” Fleet said.

“Paying college athletes is good because more talented athletes would be attracted to schools that offer comparable competition depending on division one or division two,” Carr said. “These students would also be more likely to study at a school that challenges them academically.”

On the other hand, for sports that don’t generate sufficient revenue to provide full-ride scholarships to their athletes, athletes think it makes more sense to not get paid.

“As a rower, my sport makes zero revenue,” senior rower Paige Papesch said. “This is all the more reason why receiving a scholarship at all is amazing and for revenue sports, athletes should keep in mind that they are, again, receiving a $75,000 education for free.”

This conversation has been going on for years, but the NCAA has yet to implement a plan to officially pay college athletes.